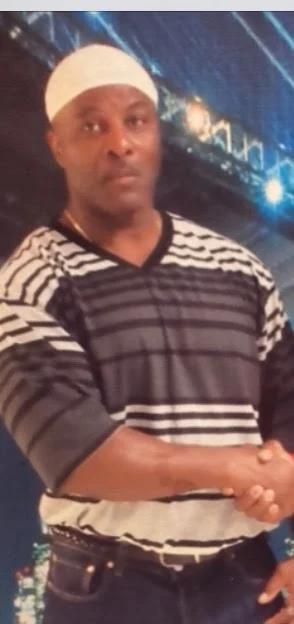

Crescent Tucker pushes wheelchairs at the Nebraska State Penitentiary.

He pushes prisoners older than him through the yard during their time outdoors. He helps them get to the prison’s medical wing to pick up their daily medications.

“One day, that might be me, and I hope somebody helps me,” Tucker said.

Tucker has been in prison for 40 years. He robbed an IHOP, a crime that ended with him shooting and killing a woman. He was 21. He’s now 62.

He’s seen plenty of death over those 40 years. Nurses running alongside gurneys, trying to revive men as they’re carted down a penitentiary hallway.

Prisoners collapsing, and sometimes dying, before his eyes.

“When you know you are aging inside of a prison, you are basically waiting on death,” Tucker said.

Nebraska’s prison population is becoming older – and sicker, too. Prisoners over 60 are the fastest growing age demographic. Over the past 30 years, that segment of the prison population grew tenfold.

In October, the state incarcerated 398 men and women aged 60 and above, many of them serving life or virtually life sentences. That means roughly one of every 14 Nebraska prisoners is at or near senior citizen age.

The increasingly geriatric prison population is costing taxpayers. In 2021, the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services spent $43 million on prison health care. That’s more than double what it spent in 2006.

The cost of drugs for inmates has nearly tripled in that time. And specific line-item costs have ballooned at even more eye-widening rates. For example: The cost of dialysis inside the Nebraska State Penitentiary has spiraled fifteen-fold just in the past dozen years.

The “lion’s share” of the increased spending goes toward the state’s oldest and sickest prisoners, says state Sen. Steve Lathrop – prisoners who experts say pose little risk of committing new crimes. Medicare and Medicaid are suspended when a person is incarcerated, which means Nebraska taxpayers foot the bill.

Last session, the Legislature debated LB 920, a criminal justice reform bill that included proposals that could have slowed prison growth and made it easier for the prison’s sick and elderly to go before the parole board for a chance at release.

Geriatric parole was one of the few proposals legislators were willing to negotiate, said Sen. Suzanne Geist, a member of the Judiciary Committee. But the Legislature couldn’t agree on other aspects of the bill, and it failed to pass.

“Our number one responsibility is to keep innocent people safe,” Geist said. “We have compassion for those who are rehabilitated and…want to get out, and yet, we have to also be careful that they are not let out before they’re ready to thrive in society.”

More senior citizen prisoners should be given that chance to re-enter society, said Sen. Terrell McKinney, who sponsored legislation last session that would have allowed prisoners with life sentences to seek geriatric and medical parole.

“You’ve got to ask yourself, is this person a threat to society?” McKinney said. “And would it cost the state less to house them somewhere else? Not to excuse why they’re in there, but it’s just looking at it from a holistic perspective.”

At the Nebraska State Penitentiary, there are now three housing units specifically dedicated to the prison’s elderly.

Men with graying hair roll oxygen tanks into their cells, McKinney described. The units have been retrofitted with ramps to accommodate wheelchairs and walkers – stairs dominate the rest of the 153-year-old building.

Fifty-three prisoners across the prison system are now medical porters, trained to work as de facto nursing assistants. The porters help older prisoners in senior units get in and out of bed, brush their teeth and eat their meals.

It’s a stark contrast from three decades ago. In 1992, Nebraska only had a few dozen prisoners over 60 — just 1.4% of the total population, not enough to justify entire units for the elderly. Then, the typical Nebraska prisoner was about 31 years old, according to corrections’ annual report that year.

Today, the average prisoner is 38. Prisoners with a life sentence skew older – the average lifer in the state is 50.

Prison leaders recently announced plans for a 32-bed geriatric unit at the Reception and Treatment Center in Lincoln.

Prisons across the country have seen the same aging trend, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

These demographic shifts were largely fueled by 80s and 90s “tough on crime” sentencing policies, several experts said. State legislatures – including the Nebraska Legislature – passed laws that enforced mandatory minimums and increased penalties. Prosecutors and judges became more likely to hand down longer sentences and life sentences, filling prisons.

In recent years, other states have found ways to shrink their incarceration numbers, even closing under-used prisons.

But not in Nebraska. The Cornhusker State’s prison population has continued to increase, and is expected to keep growing, according to the prison system’s own projections. The amount of time people spend in prison has increased as well, a state working group found earlier this year.

“It’s very easy for policymakers to increase crimes, to add new felonies to the books,” said Spike Eickholt, government liaison for ACLU Nebraska, which has advocated for prison reform. “At first glance, there’s no charge to it. The policymakers don’t really feel it until later.”

Life without parole, consecutive sentences, mandatory minimums – all are reasons why people stay in Nebraska prisons longer, and all are factors fueling Nebraska’s overall prison growth, said Ryan Spohn, director of the Nebraska Center for Justice Research at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

“Of course this is happening,” said Lathrop, outgoing chair of the Legislative Judiciary Committee. “We decided as policymakers over the years to increase penalties, so people are going to stay longer. As a consequence, we’re going to have an older population.”

That older population comes with a higher likelihood of chronic health conditions, terminal illness and pricey healthcare.

In letters to the Flatwater Free Press, current prisoners in their 70s and 80s described cancer diagnoses, joint replacements and heart surgery. They take multiple medications a day, have failing vision, hepatitis and kidney failure. Some have watched their cellmates suffer strokes and seizures.

“Every year that you spend in prison takes a year off your life expectancy,” said Wanda Bertram, spokesperson for the Prison Policy Initiative, a criminal justice nonprofit. “Somebody who’s in their 50s in prison could already have the constitution of someone on the outside who’s in their 70s.”

The Department of Correctional Services started hinting at growing health costs in 2008.

“The inmate population is becoming older and sicker, and treatment and prescription costs continue to increase,” officials wrote in a budget request.

Prison leaders continued to highlight the climbing costs: “Increased population, an aging inmate population and inflation have all contributed to the rise in medical care expenses,” read one line in a 1,065-page budget request in 2014.

Medical expenses and the number of geriatric prisoners have continued to grow in tandem, year after year.

In 2006, the department spent $19.5 million on prisoner health care. By 2021, that number had more than doubled to $43.2 million. This is partly because health care costs have in general ballooned. But it’s in large part because of the explosion of elderly Nebraskans getting care inside prisons.

Medical spending appeared to decrease slightly in 2022, only because federal COVID-19 funds went toward a portion of salary increases.

The 2023 appropriation for prison health care: $48.9 million.

“Older adults have specific health challenges, needs and concerns,” Laura Strimple, spokesperson for the department, said in an email. “As people live longer, the cost of care goes up. That’s true in NDCS as well as in the community.”

In 2010, the department started in-house dialysis at the State Penitentiary because it’s cheaper than taking prisoners outside for care. That year, it spent $20,130 on dialysis.

The expense grew by 1,461% in 12 years, reaching $314,291 in 2022, according to state budget documents.

And the department now spends $6.6 million on drugs, nearly triple what it spent in 2006.

“The number one thing here is not that the individuals are released because of expense,” Geist said. “The number one thing is that we’re looking out for public safety. That has to be the first consideration.”

When prisoners struggle to move, whether they pose a risk to public safety becomes an easier question to answer, said Marshall Lux, former state ombudsman.

“It’s an expense that you have more difficulty justifying as this person ages into a wheelchair, or where they have to be fed by other people,” Lux said. “The real question we should be asking ourselves is: When is enough enough in terms of the punitive part of keeping them in prison? When is this person no longer really dangerous?”

Researchers have consistently found that recidivism – a person’s likelihood to reoffend – drops dramatically with age. In 2017, the U.S. Sentencing Commission found that older offenders were “substantially” less likely than younger offenders to commit new crimes, though some still do. Thirteen percent of 65-and-older prisoners were re-arrested in the eight years after they were released. That’s compared to 67% of offenders 21 and younger.

Another study, this one in Philadelphia, found that juveniles sentenced to life and then later released had a recidivism rate of 1%.

For some in the Legislature, that reduced risk is still too much.

“Public safety would always override the fiscal part of it for me,” Geist said. “Financially…we know what the cost will be if someone is incarcerated. It’s difficult to calculate the cost that someone could cost society if they’re let out too soon. And that’s always the balancing act.”

Other states have adopted policies, like creating geriatric parole for aging prisoners and making lifers eligible for medical parole, that the Legislature considered but ultimately discarded last session.

Nebraska’s existing medical parole program has been called “impracticable” by the Nebraska Correctional System’s Inspector General.

Prison officials can currently refer individuals to the Board of Parole if they’re deemed terminally ill.

In 22 years, the department has approved of three people going before the board.

The board granted parole for two of them.

For lifers, like Tucker, the only way out is a commutation – when the Board of Pardons decides to shorten a person’s sentence.

Tucker has gone before the Board asking for his life sentence to be commuted four times. All four times, the board has said no.

It’s been five years since the board commuted a sentence. In 20 years, only nine people have been granted a commutation.

Gov. Pete Ricketts pointed to Laddie Dittrich as a reason not to release elderly prisoners. Dittrich was sentenced to life for a 1973 murder. In 2013, the Board of Pardons commuted his sentence. Six months after release, the 69-year-old was arrested for sexual assaulting a child.

“Inmates incarcerated for serious and violent crimes…should not be released from prison after just 15 years simply because of their age,” Ricketts said earlier this year when the Legislature was considering geriatric parole.

But bills considered last session wouldn’t have automatically released sick or old prisoners, McKinney said. The Nebraska Parole Board would have had the final say on release, and could have tried to ensure the state was releasing only sick or elderly prisoners who posed no threat.

“Most people that I’ve met that have served that amount of time aren’t the same people they were when they went in there,” McKinney said.

Geist said she’d be open to discussing geriatric parole in future legislative sessions. The challenges: Defining what age counts as geriatric, and who would be eligible for parole, she said.

After 40 years in prison, Tucker has participated in countless programs and mental health classes. He helps with peer support and is a member of a program working to reduce recidivism. His hope is to one day be an anchor of his community – outside of prison.

“If I walk out of prison today, I know from the start that I’ve got to be an excellent civilian,” Tucker said. “I’ve got to be basically immaculate. I can’t make another mistake in my life. It’s not allowed.”

4 Comments

Wonderful coverage made in a sensical manner and needs much more coverage.

But how? You can’t make people read.

Please continue reporting on this situation. I, for one, would be happy to see seriously ill inmates housed in a separate facility, cared for by non-violent inmates with proper security and a more holistic approach to care.

Unfortunately, until Ricketts is out of politics I have my doubts.

If only prisons had the goal of rehabilitation and reform of criminal behaviors. Sentences that only offer decades of warehousing individuals with no effort to restore individuals to society should come with the price tag, er, cost to taxpayers, upfront.

This is “an out of both sides of my mouth” reply. In June 1965, Dwayne Earl Pope robbed the Farmers State Bank in Big Springs and shot and killed three people and wounded Frank Kjeldgaard and subjected him to a life in a wheel chair. Frank succumbed in 2012 shortly before turning 73 and was one of my two best friends over all of those years. Pope was spared the death penalty based upon then current Federal mandates. He’s been a Federal guest and for many years, a guest of the State of Nebraska. He committed this time a day or two after graduating from college wherein he made a weapon used in the crime. He was convicted on only one count and the prosecutors were concerned about an early parole. Let’s assume that he is now 78. Does he deserve a geriatric parole. NO WAY! If my memory is correct, if he was granted such a parole, there would be police waiting to arrest him on another murder warrant as he walked out of the gate. He avoided the death penalty only due to existing policies, so he deserves to spend the rest of his life as a guest of the State, no matter the cost!

How can we get the new legislature and new governor, secretary of state, and third member of parole committee to take action on this?