Clark Rosenlof’s nightly walks routinely take him to Omaha’s Elmwood Park and inevitably toward a granite pedestal.

“I pause at the pedestal because I know something is missing,” Rosenlof said, “and that’s Bosco.”

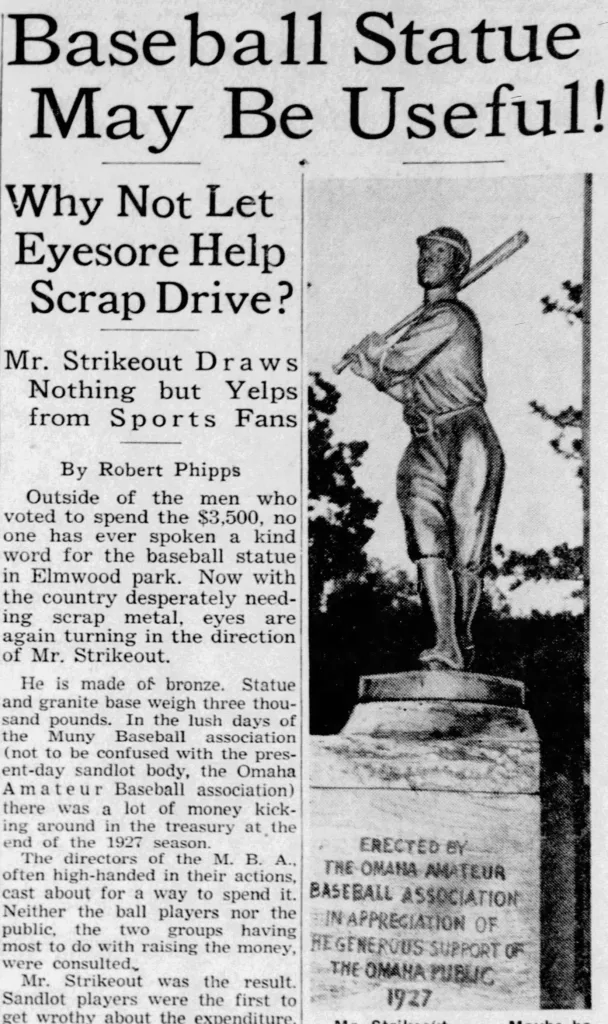

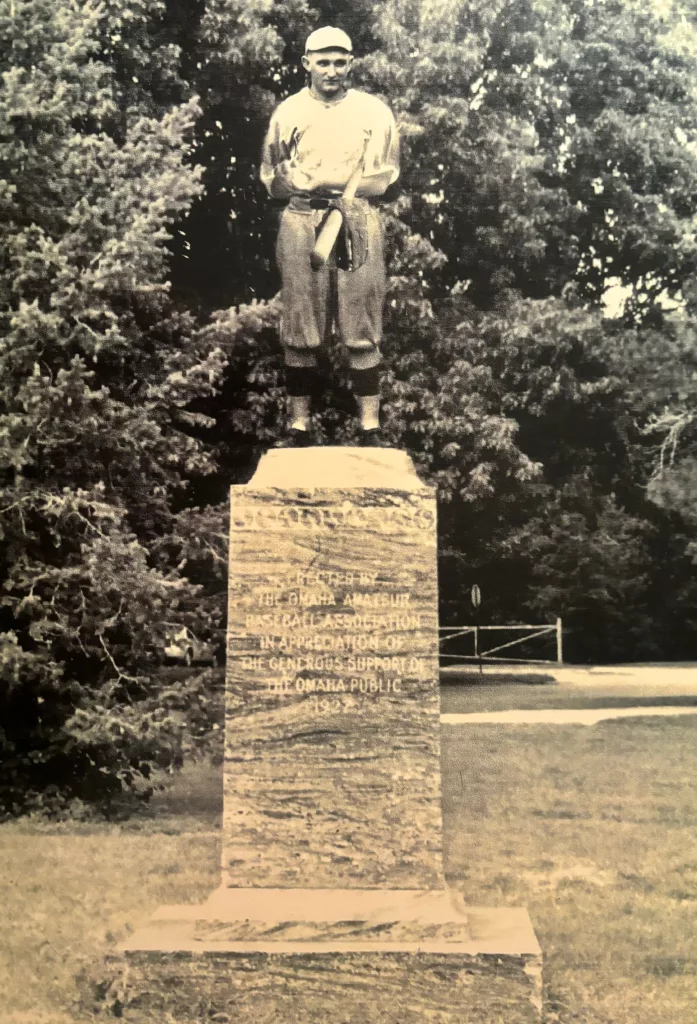

Bosco – which also came to be known as “Mr. Strikeout” – was the bronze statue that stood with a bat atop a granite pedestal, swinging in support of Omaha amateur baseball.

The pedestal still stands. But Bosco is long gone, a casualty of a world war and also, strangely, a local anti-Bosco campaign.

“He ended up serving his country,” Rosenlof said.

The statue, made by the American Art Bronze company in Chicago, drew praise for its purpose during its unveiling in September 1927. The push for the statue came from Al Scott, president of the Omaha Amateur Baseball Association.

Omaha had embraced amateur baseball, and the $3,500 statue was the association’s way of showing its gratitude. A copper box containing the names of 37,891 former and present baseball players, sportswriters, umpires, groundskeepers, city commissioners and association officers was placed in the base.

“A great peace reigns in the heart of Al Scott today,” The World-Herald reported after the unveiling. “It’s because of something new that will catch the eyes of Elmwood park visitors from now on – a bronze figure of a baseball player mounted on an imposing pedestal of granite.”

Fifteen years later, with the country at war and needing scrap metal to aid the cause, World-Herald publisher Henry Doorly’s call for action resulted in a county-by-county drive that grabbed national attention and earned the newspaper a Pulitzer Prize for community service.

A World-Herald writer, who expressed his disdain for Mr. Strikeout, suggested the statue would make an appropriate donation to the scrap drive. A county commissioner agreed and encouraged the City Council to sacrifice the statue.

Robert Phipps, the World-Herald writer, didn’t hold back his hate for Mr. Strikeout. He stated his case with three points:

– “No one knows what famous player the statue represents. (George Sisler is the reputed one; but Sisler would shoot any one with that kind of swing),” Phipps wrote in 1942 under the words “Why not let eyesore help scrap drive?”

A two-time American League batting champ with a .340 career batting average, Sisler was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1939.

– “No one knows whether it is a right or left-handed batter.”

– “No one knows whether it represents a hit or a strikeout. Consensus: It must have been a loud foul …”

After Phipps’ campaign, Bosco was drafted into service for his country.

“He was soon to become mortar shells, or shell casings,” said Jim McGee, Dundee-Memorial Park Association historian.

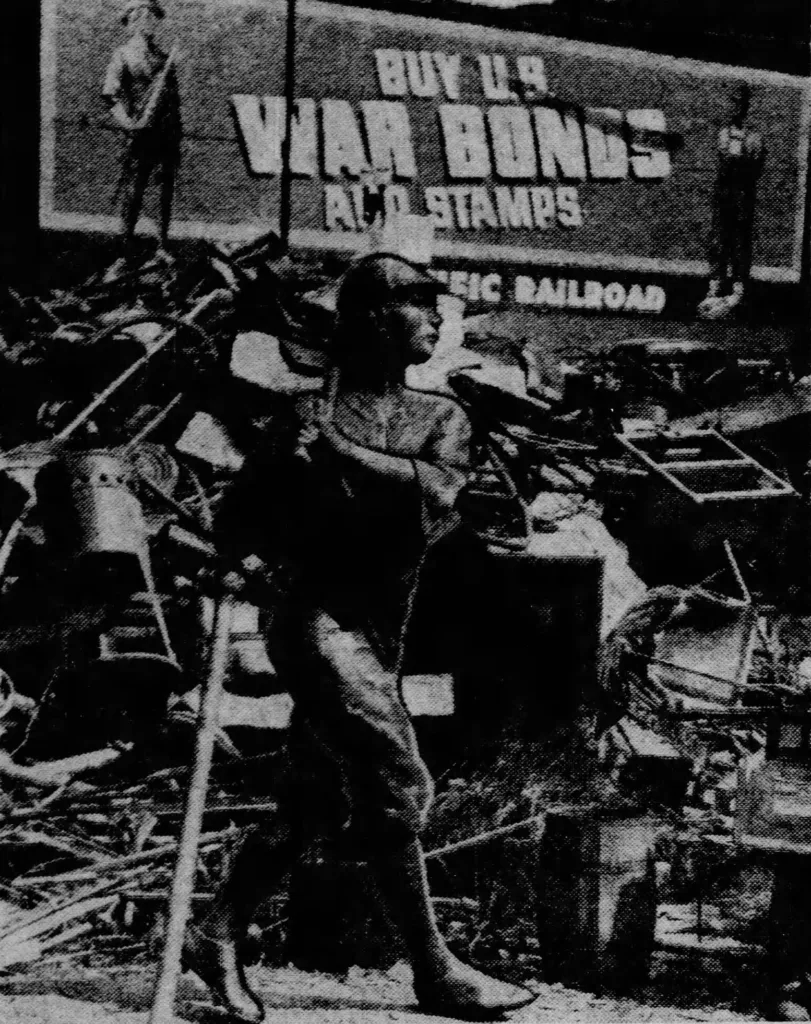

A group of Omaha Central High School students, using crowbars and wrenches, reportedly removed Bosco and delivered him to the downtown scrap mound.

One member of the group explained, decades later in a newspaper column and a letter to the editor, that the students removed the statue in broad daylight. “It was like we had permission. Everybody was putting everything they had into the war effort. Things like that were fair game.”

A World-Herald photo showed Bosco, now wearing a helmet, propped up in front of a scrap pile. An article titled “It Was Last of Ninth But Bosco Scored—as Salvage” bid Bosco good riddance. The story ended with a parting shot. “But there’s no denying that Bosco has finally made a hit (with everyone), even if he did wait 15 years with the bat on his shoulder. And 315 pounds of shell casings may make a lot of hits in the future.”

More than 80 years later, the pedestal, situated near the Elmwood Park swimming pool, remains without a statue. Two former officers of the local neighborhood association said that’s a shame.

The Dundee-Memorial Park Association, in the early 2000s, investigated replacing Bosco with a different statue, and contacted Omaha sculptor John Lajba. (Correction: This story has been updated to correct the spelling of John Lajba.)

“We felt it was something worth exploring,” said B.J. Reed, who served as association president in 2005. “We talked to John and asked him to put a concept together – still to be a baseball player.”

Jack Kubat, who followed Reed as association president, wrote Omaha’s park director in 2007 saying that he grew up playing in Elmwood Park, wondering what had been on top of the pedestal.

Decades later and after learning Bosco’s story, Kubat wrote that he had become “enthusiastic about replacing the statue, not with a reproduction of it, as it originally existed, but as a figure of a baseball player that would be seen by people visiting the Park, and inspire them to recreation and relaxation.”

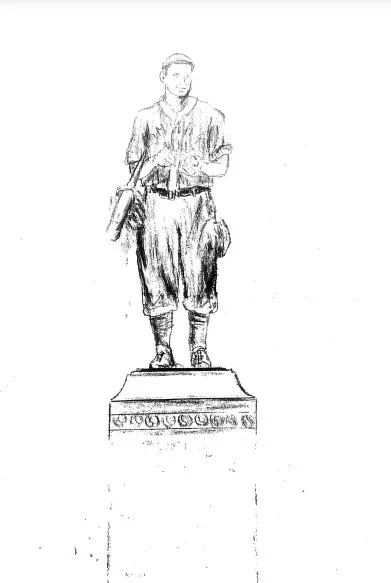

The association turned to Lajba, who created the 1,500-pound bronze “Road to Omaha” statue that sits outside Charles Schwab Field. The sculptor went to work.

His concept features a player, wearing a 1920s-era uniform, holding a ball in his left hand and a bat and glove under the same arm. He said he chose not to represent a single action – similar to Bosco – of a player throwing, hitting or fielding. Instead, he said, he sought to offer an invitation: “Want to play catch?”

“I want the statue to be a member of the family. Someone you come to visit,” he said.

The price tag, at the time, for creating the statue, transporting it to Elmwood Park and installing it on the pedestal was roughly $100,000. Kubat said the association passed on the project because of the cost and other priorities.

Matthew Kalcevich, Omaha parks director, said he is familiar with Bosco’s story. As parks director, Kalcevich also oversees the city’s Public Art Commission. He said he would love to see a statue placed where Bosco once stood.

The city has funds to maintain and restore art placed in public places, but not to create it. Should a benefactor step forward, he said, “we would absolutely embrace it.”

Moving the pedestal is not an option, Kalcevich said. “It’s a marker of history.”

McGee, the neighborhood association historian, said he hopes a benefactor might step forward to fund Bosco’s replacement.

“Most of the great things in our parks happen as the result of philanthropy,” he noted.

Lajba said he stands ready to begin work on the statue.“I would be honored to create it.”

The Flatwater Free Press is Nebraska’s first independent, nonprofit newsroom focused on investigations and feature stories that matter.

6 Comments

May have missed it, but why was it called Bosco?

Nice job on the story Kevin

Thanks, Kevin for shedding light on a lost artifact. Fascinating story!

Great piece. Costanza would approve.

Interesting story. Thank you.

Nice,what about the statue that was in Turner Park…the Statue of Liberty? It was on a raised bed of flowers and was surrounded wall pedestal.