Carie Scoggan remembers how a Dawes County district judge loomed over her like a holy figure, as her shaking hands grasped a stack of overdue paperwork she couldn’t make sense of.

Legal document after legal document had landed in her mailbox over the previous two and a half months as part of her divorce proceedings. She cried every time.

In court, she watched as others went before the judge. When her turn came, she moved toward the front of the room, her blond hair swinging as she followed the same route.

The judge asked about the overdue paperwork. Scoggan remembers not being able to string together a sentence. She was paralyzed with fear.

The end of Scoggan’s marriage had turned messy. Her husband froze her assets, Scoggan said, and her attorney told her she would be dropping her as a client due to Scoggan’s inability to pay her retainer fees — leaving her with nowhere to turn as the legal documents piled up.

“When you are out there by yourself and you’re trying to navigate waters that you’ve never been in before, it can be very hard, and the court system is very intimidating,” Scoggan said. “When you have an attorney on your side, you feel like you have this protection force field.”

That protection is becoming increasingly hard for Nebraskans living in more rural counties to access.

About a third of Nebraska’s 93 counties have three or fewer active attorneys residing and practicing in them. Twelve counties don’t have a single one, according to the Nebraska State Bar Association.

For attorneys, this means heavier caseloads and longer travel times. Judges must take on extra duties to streamline an already complicated process.

Clients, even those with urgent cases, have to wait for help. Others resort to meeting with lawyers online.

These legal deserts affect those involved in civil cases, like Scoggan’s, criminal cases where the defendant is entitled to legal representation and child welfare cases where attorneys are appointed to work in the best interest of minors.

Nonprofits and other programs are trying to fill the gaps. The state bar has several incentive programs, and a newly approved program at the University of Nebraska College of Law is working to train future attorneys in juvenile law, an area with a dire shortage of attorneys in rural Nebraska.

Even with those efforts, the problem will likely worsen in the coming years as a wave of attorneys approaches retirement age, according to the state bar.

Legal aid stretched thin

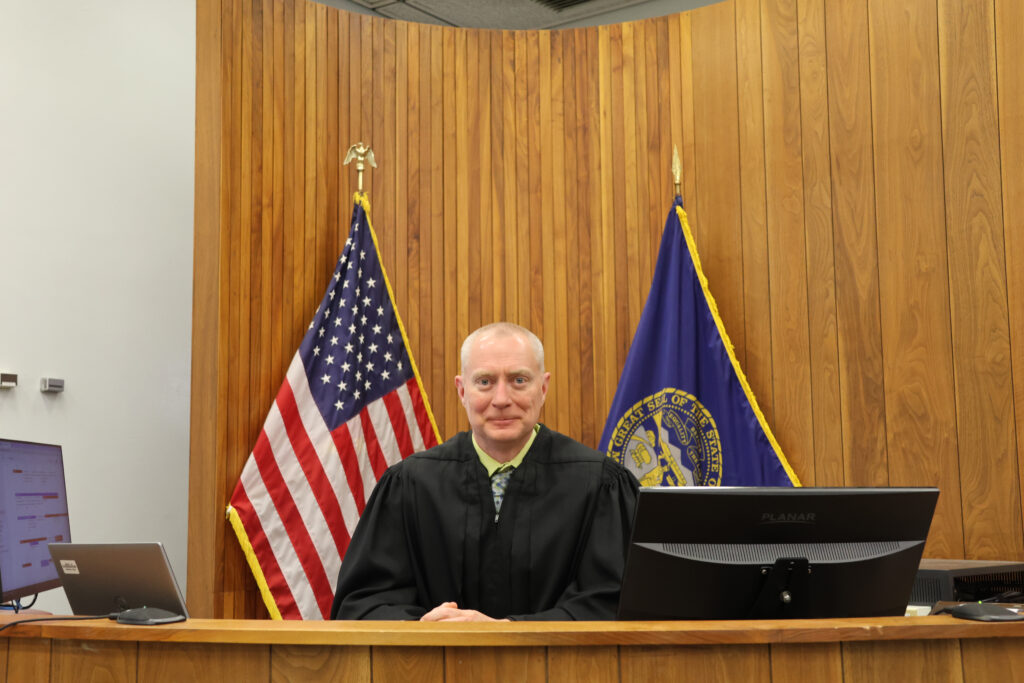

Early in Derek Weimer’s 15-year career as a district court judge in Cheyenne County, he began to expect one phrase from civil litigants in his courtroom: “I didn’t know I was supposed to do that.”

He quickly realized these people — who had no attorney and represented themselves — needed extra help.

Today, Weimer’s afternoons on the bench often consist of educating self-represented litigants, overseeing extra hearings and taking time at the end of regularly scheduled hearings to go through to-do lists.

When people don’t know much about how the legal system works, it can be intimidating, he said.

“It is sort of the equivalent of walking into an operating room and hoping that you can figure out which instrument to pick up,” Weimer said.

Weimer has made peace with having more work to do on the bench. He sees it as part of his job, he said, though it can create difficulties. Even small mistakes can cause delays, which can delay the entire system.

Many of the private attorneys or lawyers who work criminal cases in Weimer’s court come from outside of Cheyenne County.

Heavy workloads for the few attorneys in an area can affect the quality of representation in court, especially when defendants are entitled to legal representation.

“The court doesn’t get to just not appoint anybody,” said Madeline Smith, an attorney in Broken Bow.

Greater pressure, fewer resources

Some days, Smith can’t help but question how effective she is in her job as a guardian ad litem — essentially a legal advocate for kids whose well-being is in question.

After dropping her toddler off at day care, Smith might spend six hours on the road before making it back home to her family in the evening.

It makes long days even longer, and a taxing job more taxing. Many of the children Smith represents come from difficult home lives. Some are placed in foster homes.

“My biggest worry, in any case, is when this kid’s old enough to look back on this, are they going to feel like the system worked for them or did it fail? And so I always kind of have that in the background of my mind,” Smith said.

The pressure is greatest in cases that are far away.

Smith can keep her finger on the pulse of a case when it’s local. She can attend school conferences and coordinate home visits in about a month, which allows her to make better observations and recommendations.

But Cherry County, where Smith has cases, is more than 100 miles from Broken Bow. In one of those cases, children were placed in Douglas County, nearly 200 miles from Broken Bow.

In yet another case, Smith must travel nearly 200 miles west to Box Butte County.

In-home visits are a crucial part of Smith’s job. It took her four months to coordinate the Cherry County visits.

The extended days add to her struggles balancing work and life, Smith said.

It means working well into the night after she puts her child to bed, and heading into the office on Saturdays to hold meetings that didn’t fit into her hectic weekday schedule.

Attorneys in smaller communities also struggle to access the same services their clients may seek, such as mental health care.

“Once you’re outside of the major population hubs in the state, we could use more lawyers,” Weimer said. “But we could use more doctors. We could use more teachers. We could use more accountants. There are folks in those lines of work that we just need more of in these rural communities.”

Inevitable difficulties

Scoggan left the courtroom in March feeling hopeless.

That changed when a representative from the DOVES program, a nonprofit providing sexual, domestic and dating violence services in nine Panhandle counties, approached her in the hall outside of the courtroom.

DOVES helped her pay the retainer for an attorney. It provided her relief.

“Finally having an attorney that sits down with me and says, ‘Yes, I will accept this small retainer that DOVES will pay for you, and I will give you legal aid up until your divorce is final,’ is so calming. It’s unbelievable,” Scoggan said. “It took so much weight off my shoulders.”

Nevertheless, there are challenges. Scoggan’s new attorney is 75 miles away in Scottsbluff. Scoggan, who has epilepsy, can’t drive.

Her meetings have moved to Zoom.

“You don’t get that interpersonal connection. … And it seems like you become more acquainted with that person, and you can become more comfortable with them,” Scoggan said.

DOVES regularly works with local attorneys who help clients with paperwork and set up payment plans, said Hilary Wasserburger, DOVES’ director.

The process puts more work on local attorneys. To ease that burden, DOVES in 2023 received funding to hire an in-house attorney and a paralegal. It started advertising for the jobs in October.

As of March, they’d received only two applications: Law school students who hadn’t yet graduated.

DOVES isn’t alone in this struggle, Wasserburger said. Local, private law firms that would offer higher pay and better benefits in the Panhandle are having the same problem.

Closing the gaps

Michelle Paxton spent around five years as a prosecutor in Douglas and Lancaster counties before joining the University of Nebraska College of Law in 2017.

As a prosecutor, she specialized in juvenile law and domestic violence. The move to academia revealed blind spots she’d had during her time as a prosecutor.

“You’re in a position of power in decision-making and influencing power. And here I was acting in that way, and I didn’t have command of so many subjects like substance use, mental health, trauma … all of this, no idea about any of it,” Paxton said. “And I think what a disservice I did in those cases.”

In 2021, Paxton helped launch the Children’s Justice Attorney Education Program. The program set out to train students to better handle non-legal subjects that come up while working in juvenile court.

It also placed law school students in practices across the state, including in rural areas, with the hope that some will return after graduation.

The state bar association has also established programs to build up Nebraska’s attorney workforce.

Through its Rural Practice Initiative, created in 2013, the association connects rural employers with law students and lawyers.

The state bar also supports a student loan relief program for attorneys who practice in rural Nebraska, as well as a program that paves the way for college students from Greater Nebraska to receive a degree from the University of Nebraska College of Law in Lincoln.

All of these efforts are working against the clock.

A total of 108 attorneys will be 70 years of age or older in 2027, according to state bar projections. That’s 30% of the current attorney workforce in rural counties.

Garfield, Greeley, Kimball and Rock counties, all with only one active attorney as of 2022, could lose those attorneys to retirement by 2027, according to the state bar.

Weimer said Cheyenne County has two private firms, one of which only works in contractual law, not the court system. Its public defender is nearing retirement age, as are the private attorneys who represent clients in court.

In a rare bright spot, the University of Nebraska’s Board of Regents earlier this month voted to merge the attorney education program with another clinic focused on children’s justice issues.

The merger will allow Paxton and others to continue research, data dissemination and to provide access to legal representation, she said.

“The center leverages us to really be a model for a nation, because Nebraska is one of many states with legal deserts, and what we’re doing is really moving the needle,” Paxton said.

Scoggan is still navigating her divorce. She’s continuing to meet with her attorney via Zoom and collecting all the confusing paperwork she still can’t understand.

“I have friends and stuff that I could find that would take me to meet with her,” Scoggan said, “but I don’t want to be a burden on other people.”