In late March, clients started calling Brian Blackford with the same question. They sounded scared, he says. Desperate.

I got this email, they asked the Omaha-based immigration attorney. Does this mean I have to flee the country?

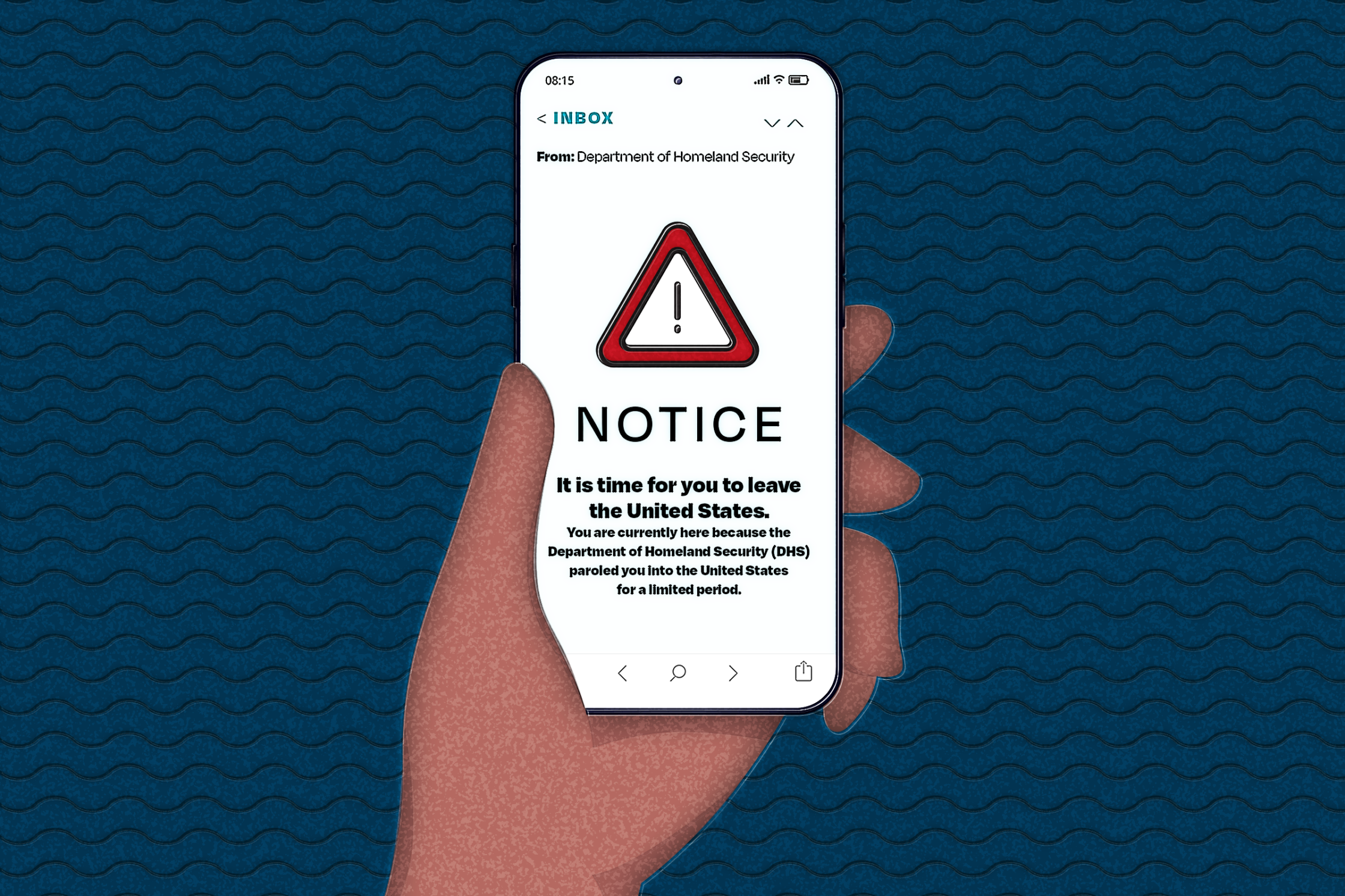

That’s what the email itself, sent by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, says in stark language.

“It is time for you to leave the United States,” it reads. “Do not attempt to remain in the United States – the federal government will find you.”

The mass email went out to migrants here legally, who had entered the United States using an app and a Biden-era program that gave people temporary legal status.

But that legal status would be terminated in seven days, the email warned. Their work authorization would end. Staying in the country could result in fines, prosecution, prison time.

Except, Blackford thought when he saw the email, it actually didn’t apply to many of his clients.

Many have pending asylum applications, allowing them to stay until an immigration court judge issues a final decision. Another had a pending green card application, because he married a U.S. citizen.

“It’s so blatantly misleading, and just obviously a scare tactic,” Blackford said. “If you don’t have an attorney that can properly advise you, that would be terrifying.”

President Donald Trump’s administration has been trying to end legal status for hundreds of thousands of migrants who entered the country through various humanitarian parole programs like the Biden-era one accessed through the phone app CBP One.

Humanitarian parole often allows people to live and work legally in the United States for two years. The Trump administration’s attempt to dismantle it is one piece of the president’s campaign promise of mass deportations.

For thousands, the directive to leave the country came via mass email – the same email that ended up in the inbox of Blackford’s clients.

“I’ve never seen this before,” Blackford says.

Attorneys like Blackford are urging their clients not to self-deport.

Immigration hardliners, including a U.S. senator from Nebraska, see the Trump administration attempting to pare back humanitarian parole as a positive step, arguing that the Biden administration abused it, allowing a larger side door into the United States.

But the government’s haphazard attempt to terminate legal status for hundreds of thousands of parolees has caused whiplash and uncertainty in Nebraska meatpacking plants and factories, lawyers and advocates say. It’s also leaving immigrant families in fear that their lives will suddenly be upended, even though they entered the country legally.

“It’s like a threat,” said Maria Arriaga, executive director of the Nebraska Commission on Latino-Americans. “It is not only terminating your employment authorization, it is terminating the possibility for everyone to build their life when they were granted entrance.”

***

The email urging self deportation appeared in the inbox of almost all 80 current and past residents of Omaha Welcomes the Stranger, a shelter for newly arrived asylum seekers.

The immediate reaction: Panic, said Juan Carlos Garcia, director of Hispanic outreach for the Columban Fathers. Shelter residents wondered, did they need to follow the instructions in this email? What would happen if they didn’t? Would Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents raid their workplaces? Stop them at the grocery store?

“We had to tell them, this doesn’t apply to you. You have a pending asylum case,” Garcia said. “It was just sent out as a mass email to everyone to scare people. So people who do not have an attorney obviously are very concerned and scared.”

CBP One worked through a mobile app. Using the app, migrants could schedule appointments at ports of entry to make asylum claims. Then, they’d be temporarily “paroled” into the country.

New CBP One appointments ceased the day after Trump’s inauguration. The administration renamed the app CBP Home, where migrants can input their travel plans to voluntarily leave the country.

Then in late March, the Department of Homeland Security took things a step further, sending out the mass email that appears to attempt to revoke legal status for people who’d entered the country through a legal process.

During the Biden administration, Sen. Pete Ricketts accused the president of “facilitating illegal immigration” through humanitarian parole. CBP One was abusing the asylum system, he wrote in his weekly column in April 2024. Parole should be used on a case-by-case basis, rather than for an entire nationality, he and other Republicans have argued.

A spokesman for Ricketts did not respond to an email request for comment.

In interviews, immigration attorneys blasted the email as misleading.

It’s not actually a deportation order, said Anna Deal, legal director for the Omaha-based Center for Immigrant and Refugee Advancement.

Unlike typical immigration agency emails, the message included zero personal information, like names and identifying numbers. The email even ended up in the inboxes of immigration attorneys who are citizens, Deal said.

Advocates and attorneys are advising people who got this email to get a lawyer, Deal said. Their other advice: Don’t leave. Departing the country in the middle of an immigration case could harm future options to reenter the country, Deal said.

“It seems pretty clear that their intended strategy is just to sow fear and confusion,” Deal said. “And to make people believe that they have to leave, which is frankly disinformation. It’s actively encouraging people to take action that will prejudice their future immigration options and that is not in their best interest.”

***

A month before the mass email, the Trump administration targeted a different form of humanitarian parole.

In March, the Department of Homeland Security announced it was terminating parole for the roughly 400,000 Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans and Venezuelans who entered through a program called CHNV parole, an acronym of the four countries. The Trump administration has asked the Supreme Court to uphold the decision to end that parole.

The announcement also sparked widespread confusion across Nebraska industries. At Honeywell in Nebraska City, where factory workers put together gas meters, workers from countries like Nicaragua and Haiti were told their last day of work would be April 24, said Andrea Hincapie, an organizer with the Heartland Workers Center.

But then management backtracked – jobs would be secure for another month, while the courts decide whether to uphold the latest Trump immigration directive.

Companies that hire Omaha Welcomes the Stranger residents started reaching out to the shelter asking, “are they not going to work here anymore?” Garcia said. Managers at Omaha factories and restaurants panicked at the thought of having to replace large numbers of employees.

Adding to the chaos: Employers only know that their employees have work authorization through humanitarian parole – not which category of parole program they entered through.

Bryan Slone, president of the Nebraska Chamber of Commerce, said businesses were left wondering, does this apply to all Venezuelans? All Haitians?

“There’s no real protocol or guidance on the employer side as well,” said Karina Perez, executive director of Centro Hispano in Columbus. “That’s leaving a lot of room for limbo and uncertainty there.”

No one knows for sure how many employees have been affected by the confusion. At some businesses, it could have been just a handful, Perez said.

At some meatpacking plants, “employers were calling in hundreds of workers based on nationality and (their work permit category) and telling them that they’d be terminated,” Deal said. “Many of those individuals weren’t even CHNV parolees. They were being told that they were going to lose their job in error.”

The United Food and Commercial Workers, the union representing thousands of meatpacking workers in the state, started hearing from Cuban and Haitian members concerned about their job security, said Leo Kanne, president of the Iowa and Nebraska union.

At one point, Nebraska meatpacking plants that employ these unionized workers thought they’d have to fire as many as 1,000 workers from Cuba, Haiti, Venezuela and Nicaragua, Kanne said. That’s 7% of the roughly 13,000 Nebraska workers the union represents.

Many companies ended up realizing the federal change didn’t apply to all workers of certain nationalities, rather, only those in a specific parole program.

“But there were a couple of them that hadn’t even been that far,” Kanne said. “They were still preparing to fire these folks, all of them.”

To lose all employees from those counties would have crippled the plants and slowed production to a crawl, Kanne said.

A federal appeals court ruled last week that migrants who entered on CHNV can’t have their statuses revoked. The Trump administration is now asking the Supreme Court to weigh in.

The constant changes to humanitarian parole make things confusing for both immigrants and employers, Slone said.

“A mass deportation notice that comes through people’s phones is very problematic for business,” he said. “It’s very difficult to react within 30 days to that many people being affected.”

If all people admitted through CHNV were to suddenly lose work authorization, it would hit industries like manufacturing, agriculture, construction and health care, four of Nebraska’s largest industries, Slone said.

Said Perez, the Columbus-area immigration nonprofit leader: “Our labor market is already in desperate need of people. These impacts will really cause devastating things to our community. Especially in rural Nebraska, losing five or 10 people is a big deal when we’re already short 100 people.”

***

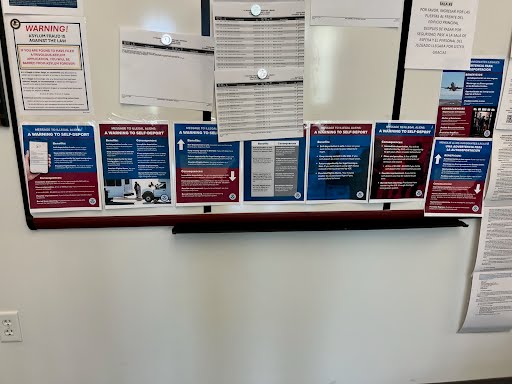

The 10 printed-out pages surround the docket of cases for the day, on a bulletin board at the Omaha Immigration Court.

“MESSAGE TO ILLEGAL ALIENS: A WARNING TO SELF-DEPORT”

The flyers list out what it says are the benefits of self-deporting. It’s safe, the flyer says. The government might pay for flights for those who can’t afford to leave.

There are images of ICE officers escorting people in handcuffs, and a man being boarded onto a white bus alongside potential consequences of staying in the country.

One flyer threatens “possible imprisonment.” The words are overlaid onto an image of a man being transported by masked guards through a maximum-security prison in El Salvador.

“I’ve never seen that in my career,” Blackford said. “It’s shocking. We have some of the highest (asylum denial rates) in the country. Now we have these notices? It’s supposed to be objective here.”

Whether these threats have legal teeth is questionable, multiple immigration attorneys said. There was no formal policy made, or notice to employers about terminating work authorization.

But while attorneys are telling their clients not to self-deport, immigrants across Nebraska are doing their own mental calculus, said Kevin Ruser, who runs the Nebraska College of Law’s Immigration Clinic.

Should we stay and risk deportation if our parole is suddenly revoked?

At a recent legal consultation held by the Heartland Workers Center, a Venezuelan man was relieved to learn he had options to stay up to date with his legal status. But he knew he couldn’t afford the likely thousands of dollars in attorney fees, said Penelope Leon, assistant director of the nonprofit.

In mixed-status families, more and more people have been turning to the Mexican and Guatemalan consulates to get dual citizenship and the right documents for their American-born kids, said Arriaga with the Nebraska Commission on Latino-Americans. That way, if they need to leave the country, their kids can travel with them.

In Columbus, Centro Hispano had a family come in for the first time last week asking for help to self-deport, Perez said.

“The fear is really high. When you feel like there’s no other reality for you now, people are like, this might be the best option for me,” Perez said. “Even if they do have status right now, it’s the unknown of how long their status will keep them here.”

The Seacrest Greater Nebraska reporter covers issues across the state of Nebraska. It is named in honor of philanthropist Rhonda Seacrest and her late husband James, who proudly led several Nebraska newspapers through Western Publishing for 40 years.

2 Comments

“who had entered the United States using an app and a Biden-era program that gave people temporary legal status. ”

False.

#1. CPB One did not confer “legal status” on any asylum seeker–no president can do so unilaterally. It simply allowed asylum seekers to schedule an appointment in the US to pursue their claim.

#2. Assuming for the sake of argument that CPB One was legal (as mistakenly suggested), it was a “legal status” conferred unilaterally by a president. As such, another president can revoke it at any time.

In any case, this confusion and chaos is 100% the fault of Wandering Joe Biden.

Actually the confusion and chaos is 100% the fault of Don Old Trump, who is now “President” of the United States sending scattershot emails to God knows who with zero information. But, you know when you are busy golfing, hosting million-dollar crypto dinners and pardoning tax cheats, a guy gets pretty busy. If legal status is revoked and Nebraska MAGA dreams come true, it will be quite a sight to see aging MAGA members happily toiling beneath their red MAGA caps in our packing houses, in Nebraska industries, and on top of roofs statewide!