When reporter Eva Mahoney arrived in Valentine in the spring of 1930, bound to profile America’s next great mystery novelist for the Omaha World-Herald, she found Mignon Good Eberhart in a “pleasant little home,” struggling to visualize her next murder.

Bewitched by her new surroundings, the big skies and grassy dunes, the author had contrived a remote hunting lodge in the Nebraska Sandhills as the site for her fictional crime. It had log doors, rough-hewn tables, “a great, deep fireplace made of native, unfinished rock,” Eberhart wrote, and a hodgepodge of antique pewter lamps, a quirk of the cabin’s late owner, a prominent trustee from the fictional city of Barrington.

“Naturally they don’t give much light, so I can employ darkened corners and shadows to heighten the horror,” she told Mahoney.

None less than Gertrude Stein would later praise Eberhart’s descriptive powers, insisting in the Washington Post that “she has the best sense of interiors – of presenting rooms,” and crowning her “one of the best mystifiers in America.” Before her death in 1996, Eberhart would publish a mind-boggling 59 novels, earning monikers like “America’s Agatha Christie” and “America’s Whodunit Queen.” One of those books made it to Broadway. Nine others hit the silver screen.

And, in 1971, she would win the Grand Master Award from the Mystery Writers of America in 1971, joining Christie and other titans of the genre. (She would have preferred the title “Grandmistress,” she later joked.)

But just now, under contract with a major New York City publisher, half-finished with her third mystery novel and humoring a journalist herself, the floor plan didn’t work – not quite.

“I don’t know how I’m going to have it architecturally correct and still be able to obstruct the view from that balcony,” she wondered aloud. “My husband has promised to come to my aid with a set of blueprints.”

He did. Months later, she finished the book, her first and only set in the Sandhills, “the most extraordinarily desolate place I had ever seen in all my life,” her narrator begins.

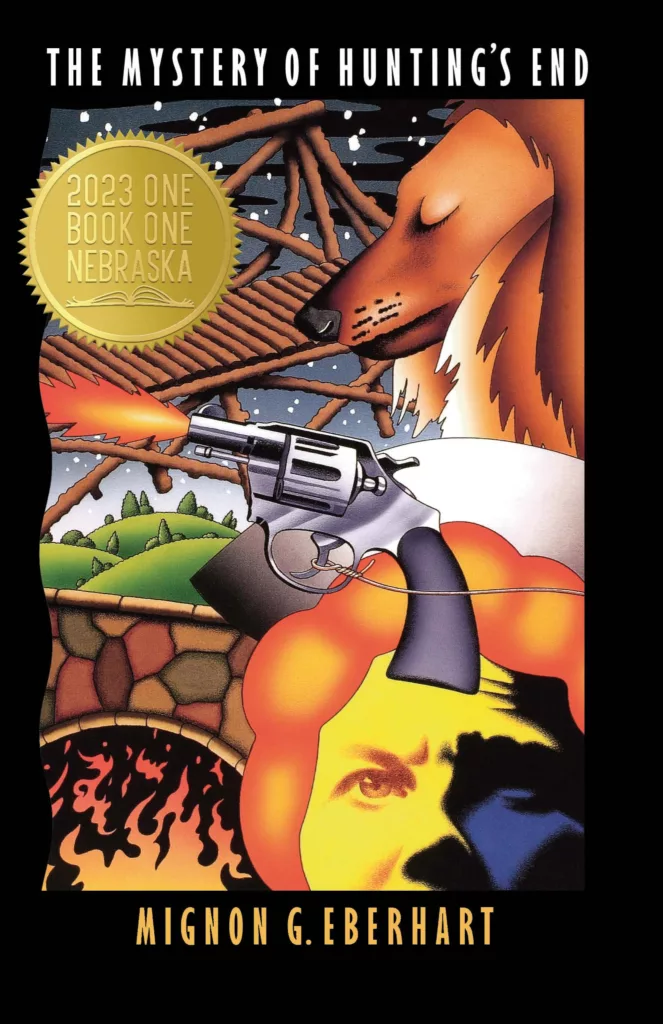

Now, 93 years after its original publication, the Nebraska Center for the Book has chosen “The Mystery of Hunting’s End” – blueprints and all – for its 2023 One Book One Nebraska program, which encourages Nebraskans to “read and discuss” a single book connected to the Cornhusker State.

Less studied than Mari Sandoz; less sentimental than Bess Streeter Aldrich; more playful than Willa Cather and Wright Morris, too; Eberhart landed somewhere beyond Nebraska’s literary canon. Perhaps somewhere behind.

But if ever there was an Eberhart revival, this is it. The University of Nebraska Press has since reissued “The Mystery of Hunting’s End” for the first time in over a decade, in addition to five other Eberhart titles that had previously fallen out of print. And thanks to the One Book designation, readers from Omaha to Ogallala will soon curl up with her work.

“The selection came as a complete and wonderful surprise,” said Clark Whitehorn, executive editor of Bison Books, the University of Nebraska Press’ trade imprint. “Unlike Willa Cather or Mari Sandoz, Eberhart has been overlooked by most readers today, so we’re delighted that (the pick) has helped to remind Nebraskans of this wonderful writer.”

***

Eberhart’s childhood home still stands on North 48th Street in Lincoln, unmarked and unremarkable, newly inhabited by a young couple with four kids drawn not by its historical significance – neither their realtor nor the listing agent mentioned it – but its “old woodwork” and a buyer’s market. No one seemed to know that within its walls, one of the world’s top-grossing mystery writers learned to read and write and transpose her fertile imagination to the page.

Born July 6, 1899, Eberhart grew up in the Methodist clutches of University Place, then a Lincoln suburb named for Nebraska Wesleyan. She read Louisa May Alcott. She read Dickens and Cather, too. And with her older sister, she played with paper dolls. For Lou, the game was finished when she’d cut out and dressed her own, writes Rick Cypert in his 2005 biography, “America’s Agatha Christie: Mignon Good Eberhart, Her Life and Works.” But young Mignonette was just getting started. She had worlds to build. Backstories to fill. Futures to unravel in the pages of her father’s old ledger books.

In 1915, following her sister’s lead, she enrolled at Nebraska Wesleyan. She caught typhoid fever and spent part of her sophomore year convalescing at St. Elizabeth Hospital – an environment, Cypert says, that would figure prominently in several of her later novels.

She never graduated. She took a job at Lincoln City Libraries, instead, where she caught the eye of a “handsome blonde giant” named Alanson Eberhart. He was a civil engineering student at the University of Nebraska, he told her. He showed up again the next evening. And the evening after that. And by the time he graduated, she once said, , “he had a degree and me.” Shortly after their wedding in 1923, they moved to Chicago, where Alanson accepted a job with the U.S. Steel Company. Before the decade’s end, they’d relocate another two dozen times.

“Let no woman whose heartstrings are inextricably entangled around a hearthstone marry an engineer,” she once wrote, “unless, indeed, it be a portable hearthstone.”

By 1925, they were back in Nebraska again, chasing Alanson’s work through the Sandhills. She tried to keep busy, but all those quiet hours in all those quiet towns – they fell like snow on the prairie, quietly accumulating until her spirit withered beneath. With no kids to rear, and nothing left to cook or clean – she emphasized her role as a housewife throughout her career – she finally turned her focus to the page.

She started her first novel while Alanson built a bridge in Niobrara; fleshed it out while he built another in Newport; and polished the final draft in Valentine, where he supervised highway construction. Doubleday quickly accepted “The Patient in Room 18.” By the spring of 1929, Eberhart was a best-selling crime novelist, her portrait splashed across newspapers nationwide. Hardly a sophomore slump, her follow-up, “While the Patient Slept” won the $5,000 Scotland Yard Prize for “best detective story of the year.”

But just now, perhaps shaken by the company of a journalist, Eberhart was despairing over her third, “The Mystery of Hunting’s End.” Triggered by what genre enthusiasts call a “locked-room murder,” the novel stars Nurse Sarah Keate and Detective Lance O’Leary, both recurring characters, and a cast of cagey socialites snowbound in a remote hunting lodge. Poison. Pistols. A plaintive collie and a missing toupee.

“I’m scared to death about the success of my next book,” she said.

***

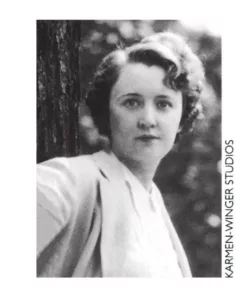

If Mahoney, in her pillbox hat and penciled lips, had come to Valentine for a hint of the macabre, to catch a twisted mind in the act, to authenticate what she called the “hardiness that one wants to associate with writers of blood-curdling tales,” she encountered instead a nervous 31-year-old woman in a classy blue frock with a “blond-gold” bob and a plaintive collie at her feet. She was “slender” and “starry-eyed” and repulsed by the hallmarks of her chosen genre.

“Mrs. Eberhart declares frankly that she would jump out of her skin if someone suddenly exploded a paper sack beside her; would promptly swoon at the sight of blood and scream lustily if confronted with one of her fictional situations.”

“Please remember that I am a beginner in the writing field,” she told Mahoney. “Right now I feel very humble when I think of the work of such writers as Willa Cather.”

Image courtesy of the Omaha Public Library

Behind what Mahoney described as a “bundle of delightful feminine inconsistencies,” however, was an artist in the clutches of imposter syndrome; a novelist still uncertain of her craft despite a one-two blockbuster debut. Unlike Willa Cather, whom Mahoney had interviewed nearly a decade before, Eberhart seemed yet uncomfortable with the writer she’d become.

“Please remember that I am a beginner in the writing field,” she begged Mahoney. “Right now I feel very humble when I think of the work of such writers as Willa Cather.”

But the longer the two of them spent there in Valentine, just a block off Main, the cottonwoods throwing shadows across her tiny front porch, the more Eberhart shed her homegrown humility. She diagnosed her genre’s growing popularity as a “reaction against the stern realism of war and the morbid, introspective post-war fiction.” And she praised the mystery story as “just what it claims to be.”

“It has no literary pretensions,” she said. “It is a game between author and reader.”

Despite all the hand-wringing, critics from Manhattan to the Sandhills soon praised “The Mystery of Hunting’s End,” now Everhart’s third best-seller in a row.

“If you must enjoy your insomnia, read ‘The Mystery of Hunting’s End’,” raved the Chicago Tribune. “Not since A. Conan Doyle’s ‘Adventures of Sherlock Holmes’ have I read a mystery story with such avid relish.”

Cover art by H. Lawrence Hoffman, courtesy of daughter Caroline Hoffman

***

She was only getting started. Just months after the journalist’s visit, she and Alanson packed their bags and returned to Chicago, where she launched into her fourth novel, “From This Dark Stairway,” another hospital whodunit. She toured Europe and settled briefly in the Maritime Alps, inspiring her sixth, “The White Cockatoo.” She visited Jamaica and Florida and Mexico City and countless other locations that made cameos in her books. Still chasing Alanson, she moved again: to Connecticut and New Jersey and New York City, too

“She has her hair done by the man who attends to the duchess of Windsor, wears beautiful clothes, is chic and charming,” wrote Fanny Butcher, one her oldest friends, in 1947, “but has her sensible little mental feet on the ground of Lincoln, Nebraska, even when the physical ones are dashing down Park Avenue.”

She divorced her blond giant. She married him again. All the while, through the Depression years and WWII and the moon landing and Vietnam, she kept writing, eight and half pages a day, every day, until the novels –– one by one –– were complete.

Cover art by H. Lawrence Hoffman, courtesy of daughter Caroline Hoffman

“I seat myself at the typewriter and hope, and lurk,” she told Publisher’s Weekly in 1974, months after Alanson’s death. “When an idea appears, I leap on it with all fours and hold it down till I’ve mastered it.”

She wrote roughly a novel a year for 60 years straight. Not all of them were “golden apples,” Cypert says. But damn the critics––she already had the readers. Her books had been serialized by the glossies and translated into more than 20 languages around the world.

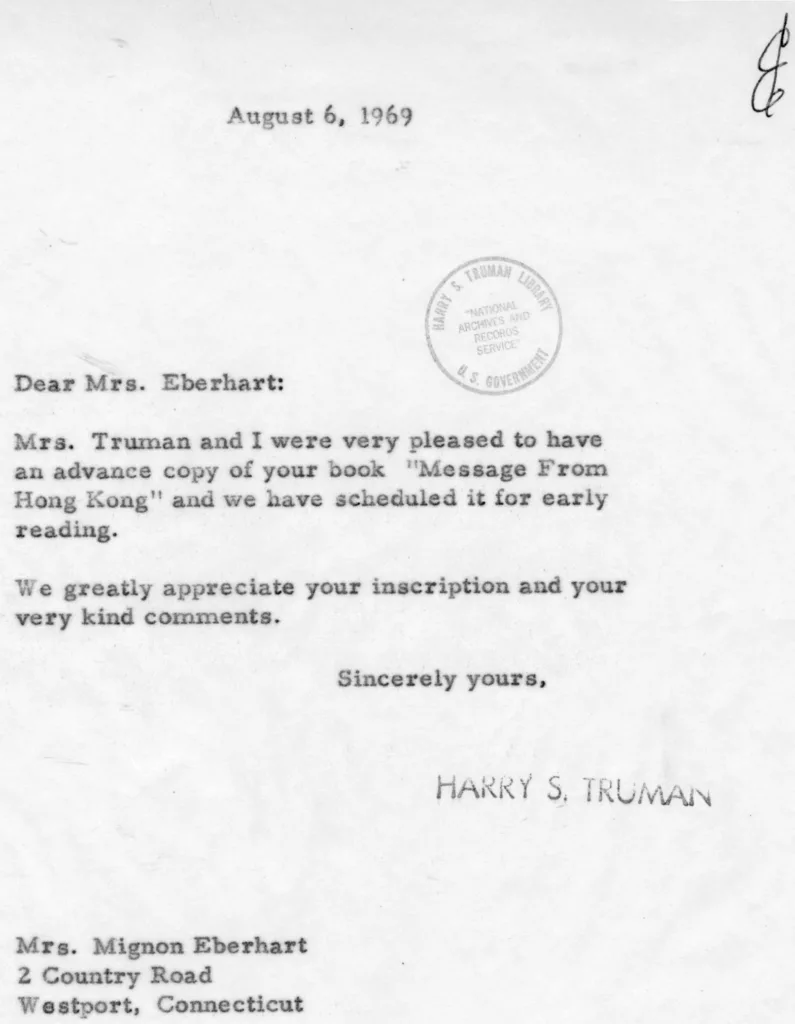

“I find it incredible that some people still rather sneer at mysteries,” she told PW. “A man I know and consider a friend was tactless enough to remark to me that nonfiction––what he called ‘serious’ literature––was edging out novels and mysteries. So while I don’t think of myself as a name-dropper, I found an opportunity to mention the enchanting afternoon I spent cruising the Potomac on the Sequoia with President Truman, one of my readers.”

Image from the Harry S. Truman Post-Presidential Papers, courtesy of the Harry S. Truman Library

***

In the winter of 1994, Bison Books editor Jay Fultz drafted a memo for his coworkers at the University of Nebraska Press. “As Max Brand is to western buffs,” he wrote, “Mignon Eberhart is to mystery buffs, and to my mind she is a far better craftsman.”

As a young boy in southeast Kansas, he’d chanced upon Eberhart’s 1939 novel, “The Chiffon Scarf,” on his family bookshelf. Gripped by her “vivid, polished style,” he once told her in a letter, he soon checked out every Eberhart mystery he could find in the Parsons Public Library––under the guise of his sister, “afraid of seeming sissy.”

Nostalgic for that childhood thrill, he was now pushing to add some of Eberhart’s finest to Bison’s growing roster of commercial fiction. Unlike so many of the mysteries then in vogue, “more violent than scary,” he argued in his memo, the Lincoln native’s early works, oozing with atmosphere, remained “stylish and readable and (a little later on) cosmopolitan.” Her local credentials weren’t likely to impact sales, he admitted, “but it gives us a respectable pretext: We would be paying homage to a native Nebraska author at the end of her highly successful career.”

His coworkers agreed. Over the next four years, Bison Books would reissue––with new introductions and splashy cover art––seven of Eberhart’s 59 novels, including Fultz’s favorite: “The Mystery of Hunting’s End.”

***

Eberhart died on October 8, 1996. It was hardly a mystery: she was 97 years old, with a broken hip and a dwindling roster of family and friends. One of them, in a plot twist befitting her novels, was the best-selling historical fiction writer John Jakes, who’d devoured her work as a kid. When he purchased a second home in Greenwich, Connecticut, in the early 1980s, he didn’t know that Eberhart, that “Olympian writer-being” from his youth, whose byline “inspired me to write fiction of my own,” lived a few houses down.

He knocked on her door. She threw him a party. They remained friends until the end. Unable to attend her memorial service, he prepared a written eulogy instead:

“Mignon’s last years were not kind to her, and so I see a certain blessing in what we observe here today,” he wrote. “I won’t remember that so much as I’ll remember her kindness, her laughter, the fun we had gossiping about editors and agents and the state of publishing….

“She was, to use a shopworn but appropriate phrase, a fine lady who will be greatly missed.”

17 Comments

What a wonderful remembrance Carson! So much information and a taste of personal connection. Thank you!

And thanks for your help in piecing together the Valentine portion, Duane!

Certainly any help that I provided was my pleasure.

Can’t wait to read one of her books. I really enjoyed this article as a former Nebraskan, and now Missourian.

Holy cow! When my daughter mentioned this article to me knowing I am a Cather fan, I was gobsmacked. I haven’t heard of Mignon G. Eberhart in decades. I read her stories as a teenager. I loved them. (Thanks, Grandma.)

Now I will have to do some browsing. Maybe add a few Eberhart stories to my Kindle and remember the fun of her books.

As always, I’ve learned something new, and that’s a worthwhile endeavor. Thanks Carson.

Very nice bio, I ran across Eberhart’s books in the Vaughn Memorial room at Wesleyan Library. I knew Ruth Vaughn for a time, 1973-1975, and only ran across the room while investigating the library, a favorite pastime of mine. An interesting item I found there, a picture of Lincoln showing J st. to be the main entrance to Lincoln.

Thanks

Hello Carson, what a great article! My great-aunt, Mildred Lenger, sister of my grandmother, Irene Lenger Benson, was a friend of Mignon. They exchanged letters all of their adult lives, though I don’t know specifically how they became acquainted. Mildred lived in Niobrara her entire life and worked as an AP reporter at the county seat in Center, NE. She died in the early 90’s and the letters, if they did survive, would be archived in the Niobrara Museum. I mostly remember being charmed by the name “Mignon,” which she pronounced “mih-nyun.” I studied music and loved the opera, “Mignon,” [mee-nyoh’] composed by a French composer, Ambroise Thomas. Seeing that name this morning reminded me of that connection. Thanks again for the informative biography! jn

How cool, Jeanmarie! I’d love to know if those letters still exist at the Niobrara Museum. I sure hope so!

Wonderful read. Love mystery fiction and will be reading Ms Eberhart’s very soon.

Great story. Would like to know her Lincoln address, as well as the one in Valentine. Hope to go there this summer to see the night sky….

Thanks for reading, Eric! Any chance you’re related to Rudolph Umland, by the way?

Great story Mr. Vaughan!

Wow so wonderful to learn of her Sandhill days and possible collection of letters….another mystery!

Wonderful article about a prolific writer. What a great way to bring her work back to the people in Nebraska.

What a lovely biographic article! Makes me want to look into producing her books in audio. Something to ponder….

That would be fantastic, Ann! Would love to see that happen.