During his final “Morning Classics” shift, Otis Twelve bid farewell with a mix of the gravity and satire that listeners came to identify him with.

“Parting is such sweet sorrow. Somebody said that once long ago and now I’ve said it again, and I’m standing by it …” he said in early October just before departing Omaha’s Classical 90.7 KVNO after 18 years. “Thanks to so many who over these years have made me a better broadcaster and a better person.”

His soliloquy served as the outro to a radio career that spanned genres – rock, talk and classical. It also spanned decades, marked by three constants: An unmistakable voice, carefully curated wit and a presence that’s long endeared the 74-year-old to fans in his adopted home state.

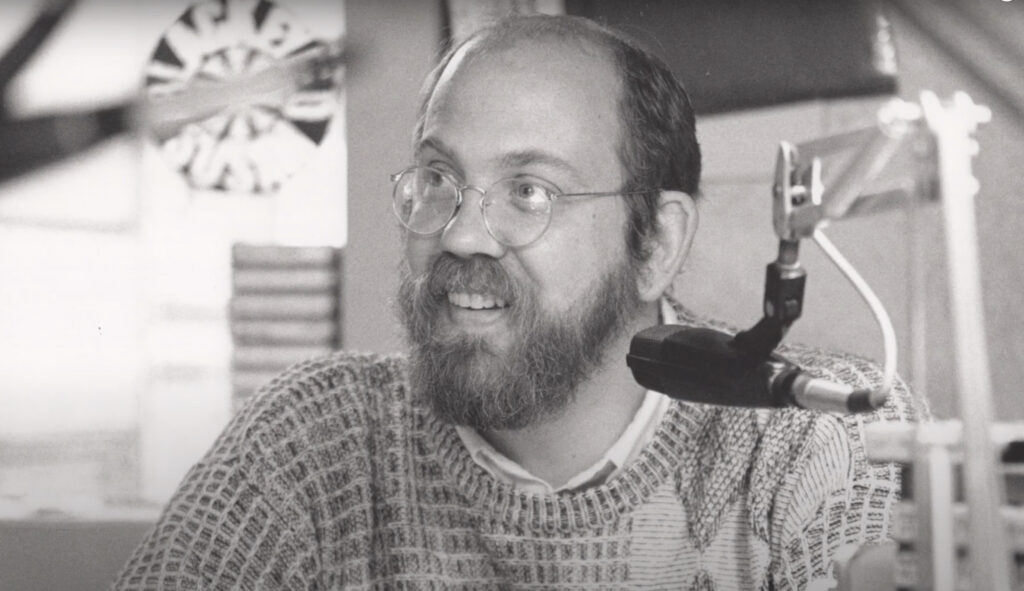

“Uniquely cerebral. Fascinating. He opens up his mind and once people get in there it’s an amazing place,” said fellow Nebraska Broadcasters Association Hall of Fame inductee Neil Nelkin.

Radio, though, was merely one letter in the call sign of Otis Twelve, whose legal name is Douglas Vincent Wesselmann.

Wesselmann, an award-winning fiction author and essayist, has lived a topsy-turvy ride.

He went from training in a Benedictine monastery to working on Robert Kennedy’s Omaha campaign and earning an FBI file. He guarded Paul Newman, chatted up Dennis Hopper, bent an elbow with Ray Bradbury, and interviewed Ann Margret and David Crosby. He narrated symphony concerts and industrial films and voiced countless commercials. He survived being raped at age 12 and addiction later in life.

His professional career offered challenges too, including his own transformation from rock DJ to mainstay on Omaha’s public radio classical music station.

“It’s been a strange story, man,” he said in that familiar resonant bass drum voice. His towering stature and gray mustache, beard and flowing locks complete the wizard-like persona of this self-described “old hippie.”

Wesselmann grew up in Philadelphia and Missouri in a conservative Catholic family. His future seemed decided at an early age: he was going to be a priest. “I knew the whole Latin rite by the time I was 10. I was an altar boy. It was really a good education but totally archaic now,” he said.

Reading provided solace and stability from an early age, though he “was terrible at school.”

Outside of books, his passion growing up was baseball. He played on sandlots and listened to radio broadcasts. They gave him an education, particularly color analyst Dizzy Dean.

“What I learned from him was just be yourself. Try to find a personality, but it’s gotta be real. He was the reason I wanted to be a play-by-play guy.”

Any desire to enter the priesthood faded. He developed a Civil Rights mindset, disturbed by “colored” drinking fountains and the Confederate flag.

At Creighton University he pushed the envelope with his “Revolution” campus radio show. He enjoyed “one of the formative experiences of my life” doing experimental stage work at the Omaha Magic Theatre. Later in his broadcast career he leaned on his time with Omaha Magic Theatre in creating on-air personalities like “The Mean Farmer.”

“It was a great introduction into not only how to use your voice, how to be on stage, but what art was, what dedication to that was, and exposure to the wide range of people involved in that creativity – the underground, the unacceptable, the outcasts,” he said.

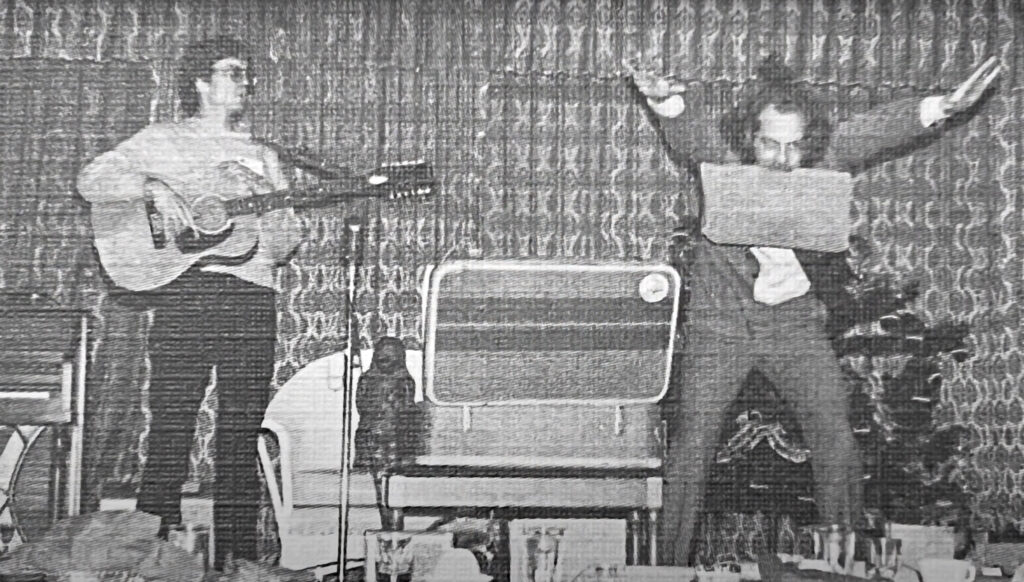

He co-founded the band Ogden Edsl, which melded music with absurdist humor and sketches, leading to songs like “Dead Puppies.”

“It was such a weird combination. Some called it rock ‘n’ roll vaudeville and that really kind of comes close. It was slapstick and then heady stuff.”

The band gained popularity in a small subculture, particularly once the nationally syndicated radio program Dr. Demento started regularly featuring them. The band started touring and performing outside of Nebraska, eventually linking up with artists in the San Francisco counterculture.

Back home in Omaha, Wesselmann met Debra Bellows, who became his wife. Her late brother, the noted realist painter Kent Bellows, was friends with Wesselmann and played matchmaker.

After the hard-living rocker made a bad first impression, Debra nearly refused to see him again. But she gave him a second chance. He’s grateful to have had her and her creative family by his side during triumphs and travails.

Consciously or not, Wesselmann explored different forms of artistic expression to cope with the childhood pain he otherwise suppressed. As a boy he was groomed and repeatedly abused by an adult lay associate of the Atchison, Kansas, monastery he later joined.

One day he took Wesselmann for a drive into the country, where he raped, strangled and left him for dead in a ditch, he said. Wesselmann managed to stagger back home. Except for a priest confidant, he didn’t tell anyone what transpired. Decades passed and Wesselmann was in recovery before he told Debra.

“The thing about my kind of trauma is you don’t admit you have it or it ever happened, and it does its business on you for years and years until you get to the point you’ve got to do something.”

For years he self-medicated with alcohol, drinking deeper into addiction. After finding sobriety in the ‘90s he finally attempted to address his pain.

At the urging of Debra, a mental health counselor, he started therapy and learned that by talking about his trauma it lost much of its power. He sought closure from his attacker and decided to return to the monastery. At the time, he wasn’t sure if he would confront or forgive – a reality that made Debra nervous.

“I think she knew I had to, but she was worried about how it would turn out,” he said. “You don’t want to go stop at the gun store first.”

He learned his attacker died in an auto accident. “It was good to know,” he said.

An unpublished novel dealing indirectly with his sexual assault became part of his recovery. Writing, he said, has always been therapeutic.

It’s also how he intends to spend a good portion of his retirement. He’s toying with a fresh take on “Faust,” the 19th century German literary work, and collaborating with Debra on a book about adults dealing with childhood trauma. He also envisions finishing an unfinished novel by Debra’s late grandmother, Louise Bellows, an early feminist “way ahead of her time,” he said.

Louise Bellows’ work was based on her bout with tuberculosis. She was sent to a sanitarium, where she met and formed a friendship with a Japanese man, Wesselmann said.

The book may allow Wesselmann to connect one romantic story with another. His late father Vince Wesselmann was a Navy combat flier in World War II. He flew missions in the Battle of Okinawa.

Generations later Wesselmann’s son Vince, named after his grandfather, married an Okinawa native who’s gifted Doug and Debra with biracial, bilingual grandchildren. The karmic circle of it all, he said, is a great thing.

Family factored into Wesselmann’s decision to retire. He wants to spend more time with them doing the things he and Debra enjoy doing.

“If I just had an apartment and nobody, I wouldn’t be retiring,” he said in September. “I’d work until I dropped. I thank my lucky stars I’ve got all this other stuff.”

Part of him hoped to evade the stream of well-wishes and tributes that poured in during his final weeks on the air. He understood though the need to say thanks and goodbye. Then there was the symbolic passing of the “Morning Classics” baton to friend Jeff Koterba, who shared the gig with him the last couple years.

“Those are some mighty big shoes to fill. Size 13, he once told me when I asked,” Koterba said. “But I’m not Otis. No one else can ever be Otis. … Every single time I open the mic, there’s a little magic in the air. Personally, I like to think it’s some combination of the magic dust of Otis and the specialness of KVNO.”

There was very little planning when it came to the arc of his career, Wesselmann said. His “strong psychic constitution” allowed him to go on the journey and believe it would work out.

He was out of work – and needing health insurance – when he learned of the KVNO opening. He decided to reinvent himself as a classical music arbiter.

He wanted to be a different kind of host in the world of classical music. It was all about puncturing pomposity.

“I kind of had the idea (that) music’s music and to just treat it that way,” he said. “I wanted to make it accessible so people weren’t afraid of it and didn’t need a degree.”

For the decision makers at KVNO, which was looking to grow its audience, it proved an intriguing pitch.

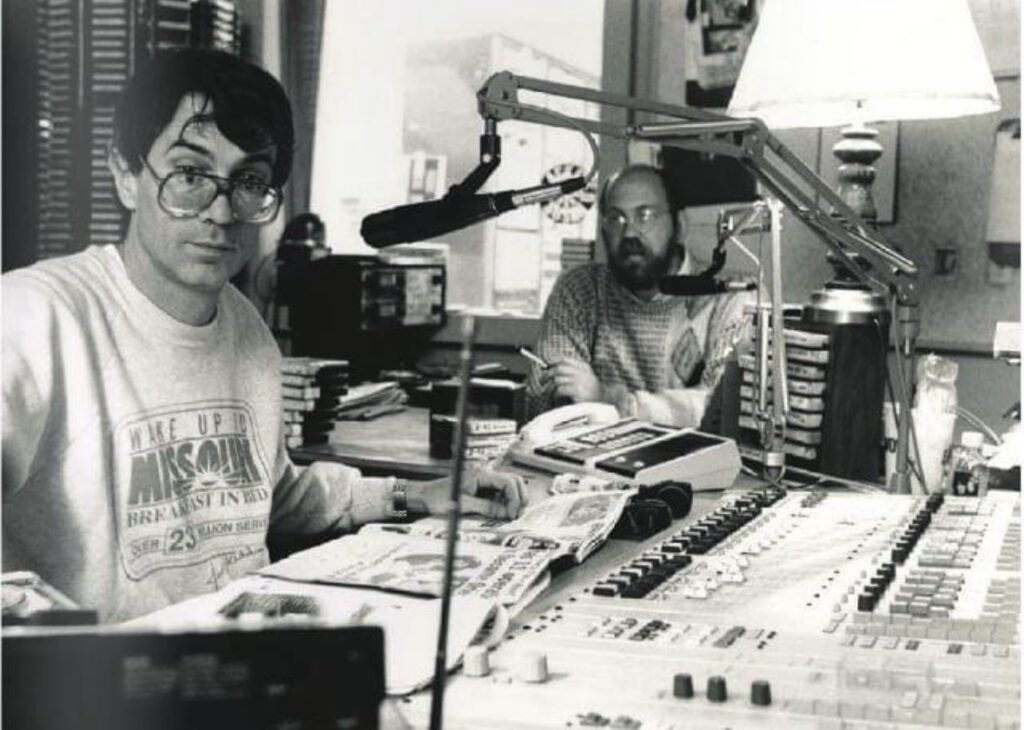

While his lack of classical bona fides made his hiring a bit of a gamble, Wesselmann was a proven journeyman on the radio by that point. He had a background in rock music and talk radio, the latter came to an end after 9/11.

He had what he described as “a really friendly show” on a local talk station. After 9/11, the station made it clear what was expected on air: unwavering patriotism.

“I said, ‘bull****, I don’t do that, you need to fire me.’ And they did,” Wesselmann recalled.

Nelkin was the manager who fired him. He said “nobody saw it coming” when Wesselmann shifted over to classical. “But I don’t think it was difficult for him because when he gets into anything he develops a passion.”

During his final shift, general manager Sherry Brownrigg called Wesselmann “the rock and the touchstone for KVNO.”

“Your dedication, your wisdom, your incredible ability to communicate, I’ve never known anyone better. … You have really taught us not to take ourselves too seriously.”

As he signed off for the last time on Oct. 4, Wesselmann found words fitting the man and the moment.

“And now for my actual exit,” he said, “I would like to quote my favorite philosopher, Marx – Groucho Marx – in song if I may, but I may cry …”

Hello, I must be going.

I cannot stay, I came to say, I must be going.

I’m glad I came but just the same, I must be going.

I cannot stay a week or two, I cannot stay the autumn through, so I’m telling you, I must be going.

“Thanks to you all,” he concluded, “thanks to everybody.”

10 Comments

My most favorite radio personality ever. He is greatly missed on air.

I have enjoyed listening to Otis since he first went on air with Z92 in 1979! Enjoy your retirement, my friend!

Space commander wack. Loved their show back in the day. It always made me laugh.

You can always count on Leo Biga, to unearth what strata layed by Omahans of repute, for us denizens!

The one and only Otis has always been generous with his talents, kindness and valuable insights. Xo cc💙

Great reflection on one of the best radio broadcasters in Nebraska (heck, in United States) history. What a voice; what a career.

I formerly had a one hour commute into the Omaha area. Listened to Otis on many of those trips! Great voice. Enjoy your retirement!

I miss the Mean Farmer !

Really nice article. Made me remember how much I miss Z92 being funny on the morning drive. I hope Douglas/Otis has a happy and productive retirement.

I had the good fortune to see and hear the Ogden Edsl band perform in the Iowa Western Community College cafeteria in 1975 (76?) – they were great! I thank Otis Twelve for making me laugh for many many years!