Last summer, Imperial farmer Dirk Haarberg made the hard decision to let some of his milo crop die. The heat and the wind had proven too much, Haarberg said, and he needed to save water for his other cornfields.

Haarberg’s water pumps also ran nonstop, he said during an interview, drawing more water than usual from the Ogallala Aquifer to feed the thirsty crops he was keeping alive.

“We don’t overwater, but when it was as dry as it was last summer, there’s not much you can do but just water 24 hours a day,” said Haarberg.

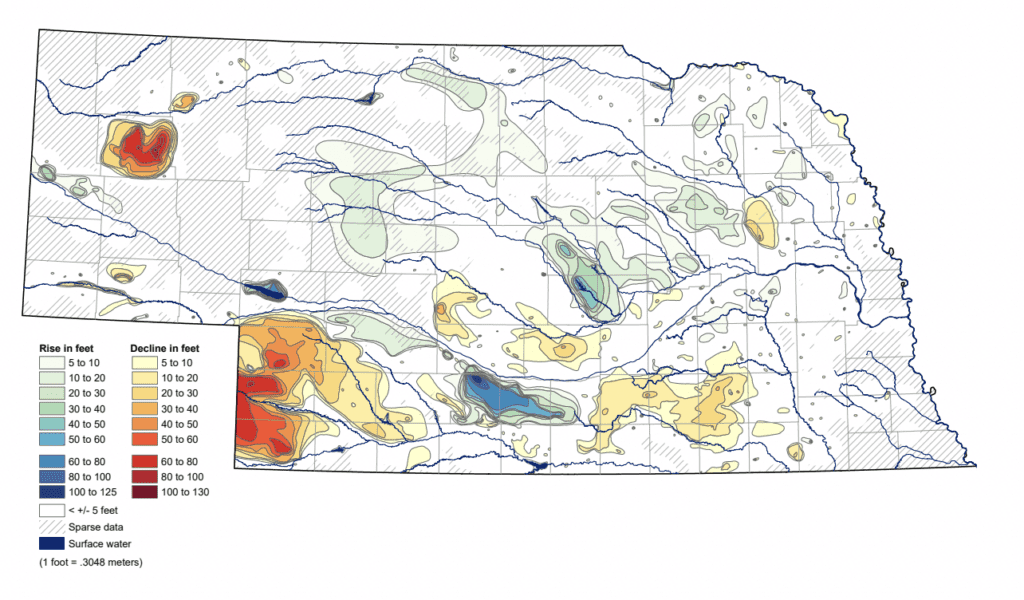

Decades of irrigating in a relatively dry area has taken a toll on the groundwater in southwest Nebraska. In Chase County, where Haarberg lives, water levels have fallen as much as 100 feet since the 1950s, before the advent of high-density irrigation, according to a newly released University of Nebraska-Lincoln groundwater monitoring report.

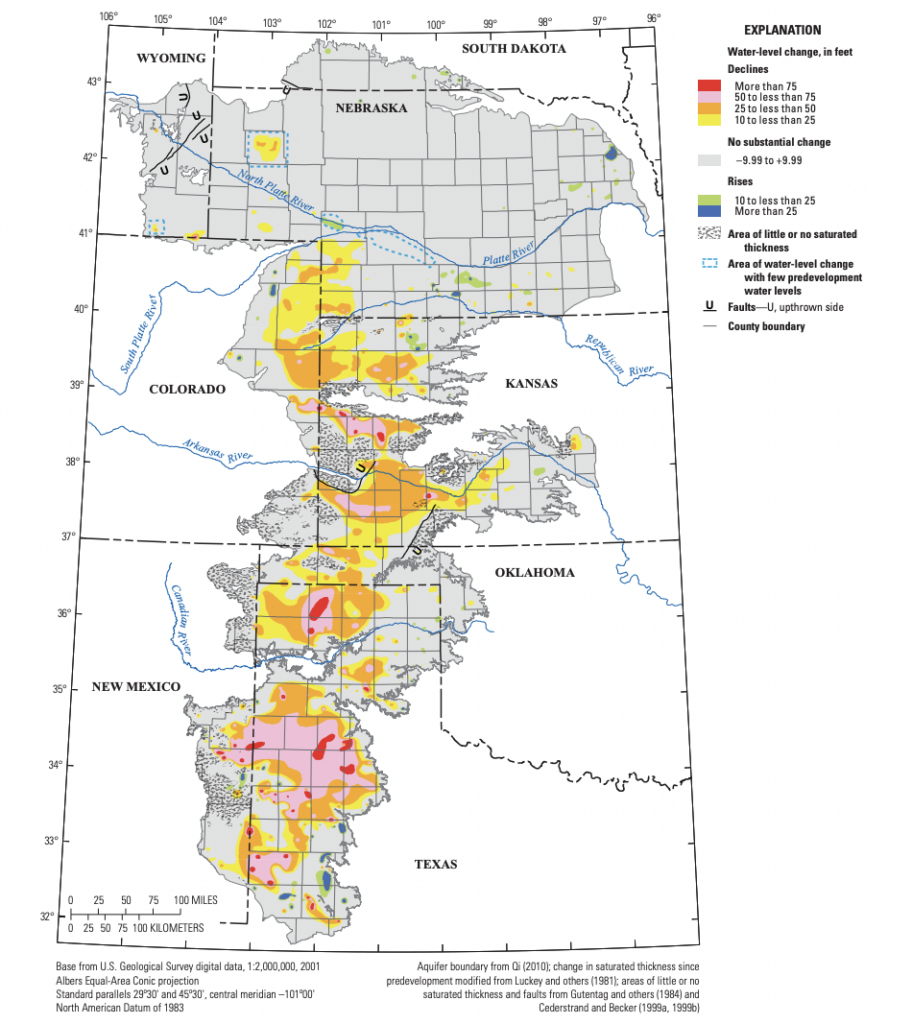

The Ogallala Aquifer is healthy and even thriving in many parts of Nebraska. The state is maintaining much higher groundwater volume than many states to the south, according to UNL water experts and decades-long mapping from the U.S. Geological Survey. Between 1950 and 2017, available water in storage in Nebraska’s part of the aquifer decreased by merely 0.34%, markedly better than the aquifer’s 36% decline in Texas, according to a Flatwater Free Press analysis of USGS reports.

“Over the long term, we’re not in bad shape,” said Aaron Young, a survey geologist at UNL and chief author of the report.

But some small pockets of the aquifer in Nebraska have been losing water at far greater paces than the rest of the state — a slow-but-steady disappearance of water that more closely resembles the troubling situation in much larger swaths of western Kansas and Texas. The decline, mostly located in four counties — Dundy, Chase and Perkins counties in southwest Nebraska and Box Butte County in northwest Nebraska — has prompted natural resources districts in those areas to closely monitor and regulate water usage for years.

Despite this work, experts say that consistently falling water levels may transform irrigation farming in these areas in the future.

“In those areas, whether it’s wet or dry, we kind of see a decline of about a foot per year, sustained over the long term,” said Young.

Nebraska isn’t grappling with wholesale water shortages like other states for a crucial reason: The Ogallala Aquifer is much thicker here. In fact, the state is home to 70% of the total water contained in the aquifer.

Nebraska’s groundwater levels tend to fluctuate with precipitation. The amount of rainfall affects how much water can replenish the aquifer, and how much water farmers need to pump for irrigation. In southwest Nebraska, where precipitation is much less than in the eastern part of the state, producers have tapped into groundwater to feed their crops.

“Had we had six more inches of rain, we’d have pumped six less inches of water,” said Haarberg.

A big part of Upper Republican NRD in southwest Nebraska is “at a net deficit” in terms of groundwater reserve because of high-density irrigation and slow natural charge, said Virginia McGuire, a hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. This decrease in aquifer thickness, sometimes with more than 50% of water storage in an area disappearing, McGuire said, is less than in western Kansas and Texas, but “still significant.”

“Once you pump it out, you just have very little coming back in,” said McGuire. “Even though you slow on your pumping because you got a lot of rain, that doesn’t really help you that much in the grand scheme of things.”

Leaders in the Upper Republican NRD decided to cap water usage at 20 inches per year in the late 1970s — making it among the first entities in the country to set annual water allocations. Before that, area farmers used to pump up to three feet of water from the aquifer per acre.

“Folks in our district … saw the writing on the wall that we were going to struggle with decline issues unless we have the ability to regulate water,” said the NRD’s assistant manager Nate Jenkins.

The NRD has since reduced the allocation several times.

With these restrictions, the district has suffered about 60% less water decline than expected, Jenkins said.

Other NRD leaders also said local regulations have helped stabilize water levels in their parts of Nebraska.

“If you look at other states, they haven’t even started doing anything … like Texas and western Kansas — they didn’t have any regulatory system set up,” said Dean Edson, executive director of the association of the Nebraska Association of Resources Districts.

Last year, Haarberg was blowing past his allocation on all his irrigation wells – about 13 inches on average per year. He had to take advantage of past years’ leftover amounts or dip into his carryforward account.

Farmers may not always be able to achieve maximum potential yield on their cornfields even while using their entire annual allocation, Jenkins said.

Still, responding to dipping groundwater levels, the Upper Republican NRD board last week voted to again reduce irrigation water allocations, this time to 62.5 inches in a five-year timeframe.

With the current groundwater reserve and how fast water is consumed, the water in the district will last for a few hundred years, so it’s not an immediate concern, Jenkins said.

“The concern is long term, slowing and eventually stopping groundwater declines so that there’s always water to irrigate with,” Jenkins said.

About 20% of irrigated acres in the state are subject to restrictions on the amount of water pumped. At different points in time, many NRDs in northern, southern and western Nebraska have also used their authority to pause certain kinds of new well drilling.

In the Panhandle, areas near Box Butte County and Hay Springs also experienced faster groundwater storage decline. These two areas are scattered with irrigation wells, said Lynn Webster, assistant manager at the Upper Niobrara White NRD, as opposed to large swaths of northwest Nebraska that are primarily used for ranchland.

This steady decline in water storage has consequences. In Box Butte County, a handful of residents have had to drill their wells deeper because of the water level drop, Webster said. He also said that area farmers will probably have to make due with stricter water restrictions in the future.

Over the long term, rainfall in his district seems cyclic, with wet years and dry years alternating, Webster said. A prolonged drought would have a more significant impact on groundwater levels, he said.

Even in parts of Nebraska where there aren’t water restrictions, some farmers have reduced water voluntarily, Edson said. There are programs aimed at preserving water, such as retiring irrigated acres and other aquifer augmentation projects.

Haarberg, the Imperial farmer, leaves his non-irrigated land fallow every three years to preserve moisture in the soil and uses equipment to prevent runoff.

“We have done things for 30 years to try and protect our water and protect our ground so that we have more available water,” he said.

The farmer would prefer that the local NRD not lower his water allocation, but he said he also understands the need to preserve the area’s groundwater.

This seems to be the direction in which his local NRD board and NRDs across the state are heading.

“We’re taking actions. If you look at their allocation over time, it has dramatically decreased,” Edson said. “If we need to continue doing that, we’ll continue to do that.”