In 2011, the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services wrote a bill that would allow well-behaved prisoners the chance to shorten their time behind bars.

Eleven years later, that same department is applying the resulting law in a way neither the state senator who sponsored the bill nor the then-director of Nebraska’s prisons intended.

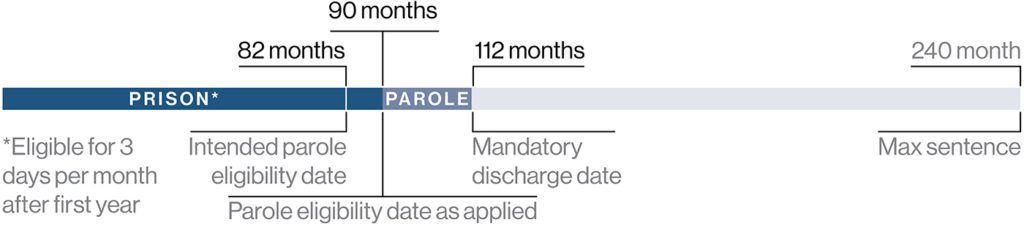

Prison officials now shorten a prisoner’s final release date, but never change the day that prisoner becomes eligible for parole.

The result: Thousands of prisoners sentenced under the law have potentially stayed in prison days, weeks or months longer than the law’s authors intended.

The debate over semantics – namely, the meaning of three dozen words buried in a state law – has made its way to the Nebraska Supreme Court, whose decision could shorten the stays of thousands of people in the state’s chronically overcrowded prisons.

The Flatwater Free Press, in partnership with the Omaha World-Herald, dug further into the case, which has flown under the radar as Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts, the Nebraska Legislature, prisons officials and prisoner advocates debate how to fix rampant overcrowding and whether to build a new prison.

On one side: The department argues that it’s properly following the 11-year-old law when it comes to calculating when a prisoner is eligible for parole. If there’s a flaw, it’s in the language of the law itself, state lawyers have argued in court.

On the other: Robert Heist II, who has been imprisoned since 2016, argues that the department is misreading the law and delaying parole eligibility.

In some cases, prisoners end up being released with no supervision – “jamming out” in prison-speak – before they even become parole eligible.

“When you become parole eligible after you’re done with your sentence, it doesn’t make any sense. That’s just ridiculous,” Heist said in an interview. “And it is contributing to overcrowding, because if you postpone people’s parole eligibility, they’re just sitting around longer.”

Nebraska’s prison good time calculations are complex. The law has gone through several makeovers during its half-century on the books.

LB191 was meant to add to the state’s already existing good time – day-for-day credit prisoners earn, which effectively cuts many sentences in half. The change proposed by prison administrators in 2011 allowed prisoners to earn three days of good time each month if they avoided certain disciplinary offenses after being imprisoned for a year.

The bill, written by the Department of Corrections and sponsored by then-Sen. Brenda Council, was expected to save the state at least $1.08 million over a decade.

Understanding “good time” in Nebraska

Nebraska good time law has gone through several revisions. The more well-known form of good time gives prisoners a day’s credit for every day served – effectively cutting sentences in half. Say a person has a 15-20 year sentence. Automatic good time would cut that in half to be a 7.5-10 year sentence. That means a shot at parole would come at 7.5 years, or 90 months.

BEFORE GOOD TIME LAW LB191

In 2011, the Legislature added another way to shorten sentences: After a year of incarceration, prisoners can earn three days off their sentence for each month of good behavior. The good time added in 2011 lets our hypothetical person with model behavior earn about 8 months toward their sentence – but only toward their mandatory release. The senator who sponsored the bill – and the past corrections director who helped write it – intended for that credit to move both a prisoner’s parole eligibility and mandatory release.

“This provision has the potential to lower the prison population, and, therefore, reduce costs,” Bob Houston, former director of the Department of Correctional Services, said at a 2011 legislative hearing. “It also rewards good behavior within the prison system.”

The current interpretation of the law – correct or not – quietly contributes to the state’s ongoing struggle with overcrowded prisons, keeping the thousands of parole-eligible prisoners sentenced since 2011 from earning up to 36 days per year toward their parole eligibility date.

Nebraska continues to grapple with one of the most crowded prison systems in the country, reaching 152% of the system’s design capacity as of December. The state has sought advice from outside consultants like the Boston-based Crime and Justice Institute on how to tackle the issue.

But little attention has been paid to corrections’ interpretation of the current law. Heist first filed a grievance of the parole calculation in June 2019. To date, neither prison leaders, the Ricketts administration nor any state senator have publicly suggested a tweak.

Getting prisoners in front of the parole board sooner is “a good thing as it relates to overcrowding,” said Sen. Steve Lathrop, chair of the Legislature’s Judiciary Committee and a state senator who has grappled with prison overcrowding for years. “Anything we can do that gets someone parole eligible sooner, I think is beneficial.”

The question now before the Nebraska Supreme Court: Should the three days a month earned for good behavior be applied to the date when a prisoner first becomes eligible for parole?

The state senator who sponsored the bill and the former head of prisons say yes.

Making prisoners parole eligible sooner was an intended result of the bill, both Council and Houston told the Flatwater Free Press.

“I introduced this bill as a means of providing additional ways to reduce the prison population and get people parole eligible,” Council said in an interview.

The days were meant to apply to both a person’s parole eligibility date and jam date, she said.

“If they’re not calculating it that way, they’re calculating it wrong,” Council said.

The bill was meant to save the department money, Houston said. Getting people in front of the parole board sooner would have played a major role in those cost savings.

“I would have definitely been in favor of affecting the minimum as well as the maximum so that people’s parole eligibility date could come sooner,” said Houston, who retired from corrections in 2013 and is now a criminal justice instructor at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. “Even though the maximum is coming down, the real effect of reducing the population is their ability to parole sooner.”

But the state is simply following the letter of the law, state lawyers have argued to the Nebraska Supreme Court. That law as written, they say, doesn’t allow for the extra good time days to go toward parole eligibility.

Corrections doesn’t dispute what Council and Houston said about the intentions of good time in 2011 legislative hearings, according to court records. But the department argues it’s irrelevant.

Parts of Heist’s claim are outside the court’s jurisdiction, the state argued during oral arguments in September. State law outlines that “…every committed offender shall be eligible for parole when the offender has served one half of the minimum term of his or her sentence…” and that good time “shall be deducted from the maximum term.”

This interpretation of the law has potentially affected thousands of prisoners who could have had at least a little time shaved off their sentences. But the most egregious cases are those prisoners who “jam out” before even becoming parole eligible.

In 2019, the department told Heist that 62 prisoners at the time had tentative release dates that preceded their parole eligibility because of their earned good time.

As of March 2022, the prison’s roster listed as many as 306 individuals sentenced since 2011 who were released before they became eligible for parole.

“When you become parole eligible after you’ve done your sentence, that doesn’t make any sense,” Heist said in an interview.

Those prisoners – whose sentences should have included a shot at parole – become “guaranteed jam outs,” Heist said.

Under questioning at the Nebraska Supreme Court, the state’s lawyers didn’t dispute that inverted sentences – when mandatory release actually comes before parole eligibility – can and do happen.

“Yes, it is possible that [inverted sentences] can occur,” Scott Straus, assistant attorney general for the state, said during oral arguments. “However, the plain language of the statute does not let us even get to whether that result is absurd or not.”

“Is it an absurd result to have inverted sentences?” one justice then asked Straus. “Or is that just a byproduct of the statutory language created by the legislature, which, whether they intended to or not, was what happened?”

“Yes, your honor,” Straus said. “I believe it is simply a byproduct of it.”

Six months later, the court has yet to issue an opinion.

The Nebraska Department of Correctional Services would not respond to questions about ongoing litigation, spokeswoman Laura Strimple said in an email.

The legal issue at play isn’t clearcut, according to a longtime Douglas County judge.

After reading the state’s good time laws, Douglas County District Judge Peter Bataillon said he could see how applying those extra three days a month to parole eligibility could be argued either way.

“Thank God that’s up to the Supreme Court to make those big decisions,” Bataillon said. “But the Legislature could very easily change that law if they wanted to.”

The good time law, as currently applied, removes parole as an option for some prisoners – even though parole is generally regarded as a better way to reacclimate prisoners to society.

Parolees have required check-ins with their parole officer, and must line up a job and a place to live. The board often requires them to complete certain clinical programming like substance abuse treatment and violence reduction programs before being released.

Not applying good time days toward parole eligibility removes an incentive for good behavior, the very thing the additional good time days were meant to encourage, said Doug Koebernick, inspector general of the Nebraska Correctional System.

“That parole eligibility date is a carrot,” Koebernick said. “That’s a really great incentive to get your act together, to get things done, do what the board of parole wants you to do.”

In the recent report by a state-led working group reviewing criminal justice policies, all committee members, including both Republicans and Democrats in the Nebraska Legislature, agreed that it’s preferable that prisoners are released with some form of supervision, either parole or probation.

“You don’t just want someone walking out of a maximum security prison, they’re not ready for it,” said Spike Eickholt, government liaison for the Nebraska ACLU. “You’re setting them up to fail. Society is better off having that supervision.”

It’s unclear what would come of a Supreme Court decision. And it isn’t the first time the department’s calculations have resulted in a jam date that comes before parole eligibility.

In 2014, an Omaha World-Herald investigation led the department to realize it was using a flawed formula to calculate sentences, releasing more than 200 people too early. Those miscalculations also resulted in more than 100 prisoners being released before they were eligible for parole.

The department hadn’t acted on a Nebraska Supreme Court ruling from 2013 detailing the proper way to calculate sentences with mandatory minimums. Houston, the director at the time, told the World-Herald that he hadn’t been aware of the ruling until informed by the newspaper.

“The other question would be, once the Supreme Court decides, [is the department] going to change the way they do business? Which is also an issue that came up in 2014 with the miscalculation of sentences,” Lathrop said.