Christine Knust planned to continue growing the journalism and yearbook program at Plattsmouth High School this year.

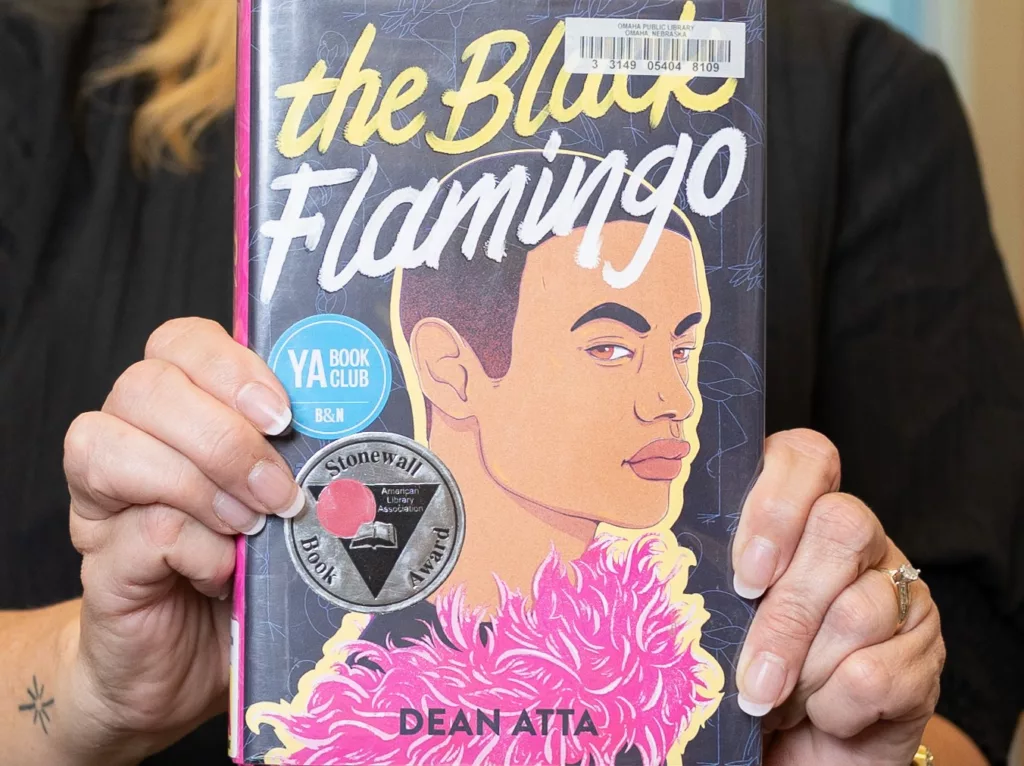

In her two years as the school’s librarian, Knust had nurtured the program from six students to 37. She also had grown and diversified the school library, adding titles by LGBTQ authors and writers from different ethnic backgrounds, she said.

Knust, who taught English for nearly 30 years in several districts, believed she’d retire at Plattsmouth Community Schools. Instead, she resigned in May.

“I think Plattsmouth has the potential to be an amazing district, and it was when I first got here … I loved what I’ve gotten to do here, it’s tearing me apart leaving my kids,” Knust said.

Administrators at Plattsmouth Community Schools last spring moved 49 books from the shelves into a box that sat in the high school principal’s office awaiting “further review,” according to emails obtained by the Flatwater Free Press. The move, as Omaha news station KETV reported at the time, was in response to a request by a school board member.

Plattsmouth isn’t the only Nebraska community in recent years where the library has become a battleground.

From the state’s rural southwest corner to the larger cities in the east, school and public libraries have seen a flood of book challenges, according to public records and interviews with current and former librarians.

The influx mirrors a national trend, one often pitting parental rights and content concerns against fears of censorship and allegations of intolerance since many of the contested books deal with race or LGBTQ issues.

In a few communities, the tension has spilled out of the library.

School board members and library staff in Nebraska say they’ve received irate emails and been verbally attacked at school board meetings by people seeking to remove books.

“We simply cannot allow a few loud voices to determine what information and ideas our students have access to,” said Chris Haeffner, a liaison for the Nebraska School Librarians Association.

In some places, anger and outrage are now flowing in the opposite direction, too.

Plattsmouth residents launched a petition to recall Terri Cunningham-Swanson, the school board member who requested the 49 books be removed for further review last spring.

In Papillion La Vista, a board member who outspokenly supported removing certain books resigned in October, citing attacks from political opponents.

To better understand how these fights play out in Nebraska communities, the Flatwater Free Press requested public records tied to book challenges from seven different libraries over the 22-month period between August 2021 and June 2023.

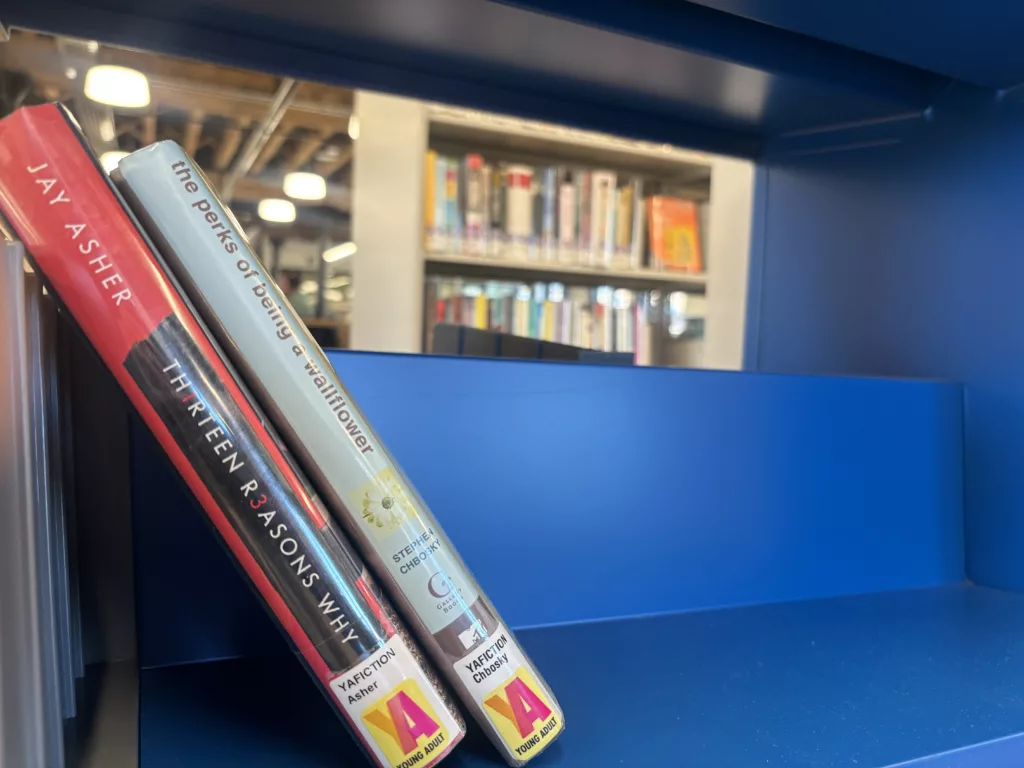

Those records revealed 127 challenges – many of which remain under review. Contested titles ranged from literary classics “Beloved” by Toni Morrison and “Slaughterhouse-Five” by Kurt Vonnegut, to contemporary works such as the graphic memoir “Gender Queer” and the nonfiction book “This Book is Gay.” Several titles, including “The Perks of Being a Wallflower,” appeared on multiple challenge forms.

Challenges were made at Fremont’s Keene Memorial Library, Lincoln City Libraries, Wauneta-Palisade Schools, Norris School District, Kearney Public Schools, Papillion La Vista Community Schools and Plattsmouth Community Schools.

Librarians interviewed for this story say they’ve never dealt with this many book challenges. The division it’s created is immense.

“We’ve had more requests in the last two years than what we’ve had probably combined in the last 10 years,” said Vicki Wood, former youth services coordinator for Lincoln City Libraries.

In September, the American Library Association reported that documented censorship attempts this year were on pace to exceed 2022, which set a 21-year record with 1,269 attempts.

Since the pandemic, almost every state has seen an uptick in challenges, according to the ALA.

Judy Henning, the former director of libraries at Kearney Public Schools from 2005-2018, said the district only received two book challenges during her time. Since retiring, Henning has served on five book review committees.

“Before, if a parent wanted to object to a book, they were directed to the school librarian who would discuss the book with them,” Henning said. “And 90% of the time, they would both understand why the book was in the library after speaking about it.”

Who is making these requests to remove books from libraries has also changed.

Prior to 2020, most of the requests were from individuals, according to the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom. In the first eight months of this year, the office documented a group connection in 28% of the efforts to censor books, though it noted that’s likely an undercount.

According to a spreadsheet compiled by Tasslyn Magnusson, an independent researcher partnered with PEN America, there are nearly 190 online groups and organizations behind these requests.

Nebraska organizations listed in that database include Moms for Liberty Douglas County and Protect Nebraska Children.

None of the requests obtained by Flatwater Free Press listed a group or organization affiliation.

Kathy Faucher, a member of the Douglas County chapter, said the group reads excerpts from books, as well as book reviews to decide which titles go on its list of inappropriate books.

The goal is to encourage chapter members to become more involved in their children’s education, Faucher said.

“It’s up to you as a parent if you want to raise that issue with your school,” she said. “And if you’re concerned enough, maybe you want to run for school board, like parents should be involved.”

Allie French, founder of the conservative group Nebraskans Against Government Overreach, said her organization started advocating for parental oversight in education in response to mask mandates in 2020. She said she has not personally submitted a book challenge but members of her group have.

“We the people have as much access and transparency to all that our government is doing, and that includes the public schools and public libraries that are taxpayer funded,” French said.

French, who is running for a seat in the Nebraska Legislature, said she has no issue with representation of certain communities in the challenged books.

In the records Flatwater obtained, books with themes of LGBTQ+ relationships, drug use and racism were among the most challenged.

One request for reconsideration by Vanessa Fanning for Wauneta-Palisade Schools stated that some books “encourage acting on homosexual feelings & normalizes LGBT lifestyles,” as a reason to remove certain titles. Fanning did not answer phone calls seeking comment.

Nationally, seven of the 13 most challenged books in 2022, as measured by the ALA, included “LGBTQIA+ content” as one of the reasons for why the book was challenged.

Peter Bromberg, associate director of the national political action committee EveryLibrary, said that some librarians have been told by administrators to lay off on LGBTQ+ themed books to avoid potential controversy.

Another source of objection: content deemed sexually explicit by the person seeking to remove the book. All 13 of the ALA’s most challenged books in 2022 included sexually explicit content as one of the reasons for it being challenged.

Sexually explicit content was a primary reason three parents in Norris School District challenged “The Perks of Being a Wallflower” in February 2022.

Parent Jaime Schmidt, in a written statement submitted to Norris’ review committee, said the book “in effect ‘teaches’ teen masturbation” and promotes a moral worldview “that is anti-virtue” and very different from what the community has traditionally valued.

Schmidt’s statement referenced a scene where a character convinces – or “manipulates” as Schmidt wrote – his girlfriend to give him oral sex in front of the book’s protagonist.

“These action scenes in the book are illicit, they feed bad images of sex into young minds and make them more interested in making sex a priority in their lives, viewing sex and replaying it in their minds which will not only ‘reduce productivity’ … but cause guilt and confusion.”

Schmidt said she worries these books will expose children to topics they’re not ready to learn about without appropriate guidance.

“We really hope that a teacher or counselor at school can be a sounding board, because I am concerned that parents are not as involved as they should be,” Schmidt said.

All three challenges cited specific page numbers or passages containing concerning content. All three also said they didn’t read the book in its entirety.

Those against removing books often respond by pointing out that the people seeking to remove or restrict a book rarely read it in its entirety.

In the request forms Flatwater obtained, only eight said they had read the books in their entirety.

Nationally, librarians are concerned that those submitting challenges are relying on questionable sources, such as online groups like Book Looks and LaVerna in the Library. Some Nebraskans have cited these websites as sources in their challenges.

Annette Eyman, director of communications for Papillion La Vista Community Schools, said she’s found that many of the passages listed on these sites aren’t actually found in the books.

In schools it’s up to individual districts to create policies, many of which typically rely on committees to review challenges. The makeup of these committees varies from district to district.

Norris, for example, includes students on its committee.

In response to an overwhelming number of challenges, though, some districts have changed their policies and created restricted access sections in their libraries.

Kearney Public Schools made this transition last spring. By having parents and guardians opt their children in or out of a system that oversees what their student checks out, the district eliminated its request for reconsideration policy.

Kearney Superintendent Jason Mundorf said parents have largely responded well to the new policy. So far, 40 parents and guardians have chosen to have oversight of what their student checks out.

“… I think our board felt that instead of a more overarching process of removing books, they (parents/guardians) get to do that on an individual basis so to speak with their own decision making,” Mundorf said.

Plattsmouth Community Schools transitioned to a similar policy. After pulling 49 books in April, the district created a restricted-access section that parents can opt into. A committee offers recommendations on specific books and the school board makes the ultimate decision. The 49 titles have remained unavailable during the review process.

Plattsmouth Superintendent Richard Hasty declined to comment on the decision to pull the books pending review.

Emails show that Cunningham-Swanson sent a list of books that she identified as “extremely problematic and inappropriate for school libraries.” She asked that the books be immediately removed from the middle and high school libraries while under review.

Now community members are trying to remove her from the board.

Plattsmouth resident Ryan Whitmore, who doesn’t have children in the district, led a recent attempt to recall Cunningham-Swanson at the request of several parents.

“They reached out because it’s hard to put your name behind recalling a politician because there might be people who take action that’s not peaceful,” Whitmore said.

Cunningham-Swanson did not respond to multiple emails and phone calls seeking comment.

That initial petition filed in July failed after organizers fell short of the minimum number of verified signatures needed to proceed.

The Facebook group Recall Terri Cunningham-Swanson is again attempting to boot Cunningham-Swanson from the board.

As a result of the intense criticism Whitmore faced, Plattsmouth resident Sarah Slattery is leading the second recall attempt. She said she is motivated by her opposition to literary censorship in public schools.

Slattery, who unsuccessfully ran for a seat in the Legislature in 2022, said she also has faced intense backlash from some community members. The Cass County GOP Facebook page shared a photo of Slattery and a copy of the recall petition, which includes Slattery’s address and phone number.

“I’m not going to be intimidated, but it was in pretty poor taste,” she said. “I’m a single mother and that possibly puts me in harm’s way because there are people that go too far on any side of a political issue.”

Nebraskans seeking to remove books from schools also say they have faced intense criticism.

In Papillion La Vista Community Schools, former board member Brittany Holtmeyer, who supported the removal of certain books, cited continued harassment as the reason for her resignation.

“I have been attacked verbally and in writing, I have had misinformation spread about me on social media and public comment, my car has been vandalized twice during board meetings and I have had to deal with a stalker,” Holtmeyer wrote in her resignation letter.

Fellow school board members were among those who criticized Holtmeyer’s actions during her tenure.

Tensions over books also have created division on Plattsmouth’s school board.

Cunningham-Swanson has moved to delay consideration of the review committee’s recommendations because, according to fellow board member Jeremy Shuey, she doesn’t believe they go far enough.

After several other board members unsuccessfully asked Cunningham-Swanson to drop her delay tactic during the October meeting, Shuey took to Facebook to voice his frustrations.

“You forced the board President’s hand to shut you down earlier because you chose to do your own thing when it pleased you. … You consistently pull snippets from these books and use them to advocate for their banning. Your actions are disgraceful,” Shuey wrote.

Plattsmouth’s review committee recommended returning 38 books to the shelves, restricting 10 and removing one, Ellen Hopkins’ “Triangles,” from school libraries.

One of the books on Cunningham-Swanson’s list was “Red, White & Royal Blue,” an LGBTQ romance novel that was added to the library collection by Knust, the former librarian who has since taken a teaching job at Ralston Public Schools.

At the time, she didn’t anticipate receiving any feedback about the decision to add the book. But, she did hear one reaction before the book disappeared.

“One of my students shared how it was the best book he had read and the first romance novel he was ever able to relate to,” Knust said.

If Plattsmouth’s board adopts the review committee’s recommendations, “Red White & Royal Blue,” will be placed on the restricted content shelf.

The Flatwater Free Press is Nebraska’s first independent, nonprofit newsroom focused on investigations and feature stories that matter.

3 Comments

The example that gives a solution to the issue is found on almost every other media. Age appropriate ratings for books. TV, movies and other media have had such ratings for decades. Why should books be different?

I suppose written requests for text removals are more “mostly peaceful” than simply burning libraries to the ground as is far more historically traditional.

Gotta love these librarians who, for years, have been adopting titles that would shock the broad community, and using public funds to do so.

When the blowback hits, they whine about being “under attack”! Sorry, you don’t bring pornography to a fight about decency and proper use of public funds and then make absurd claims about being under attack.

Either defend this trash, or stop whining about being questioned about it. Can’t have both, dear librarians.