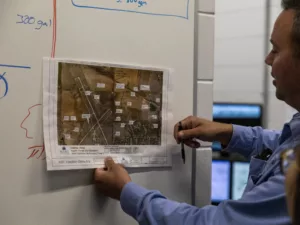

HASTINGS–Marty Stange kept adding the worrisome maps to a file folder on his desk. Hastings’ veteran environmental supervisor gathered the maps from a 200-square-mile area surrounding the city, aerial photos marked with dots whose size indicates how much uranium is found in the water supply.

Some weeks, those dots looked big to Stange. And some weeks, the dots blew up into giant bubbles, to a size that caused Stange’s eyes to widen – and prompted him to order additional testing.

One irrigation well tested 322 parts per billion of uranium in 2011, more than 10 times the legal limit for drinking water set by the Environmental Protection Agency. That well is located only four miles upstream of a municipal well.

And Hastings’ own wells – those used to supply drinking water to city residents – saw significant jumps in uranium and radiation, too, levels nearing the limit set for safe drinking water.

“It was like ‘Oh, no!’ It seemed like the more you look, the worse it gets,” said Stange.

Stange had already heard about high uranium levels in groundwater in the Platte River valley, but had no idea why Hastings would see elevated uranium levels, too. So he called experts, including Karrie Weber, a University of Nebraska-Lincoln microbiology professor.

Weber might have an answer. She has dug deep — in fact, drilled 120 feet deep into dirt below Hastings’ water table — to find out why.

“Water is not just water; water is just a reflection of what those fluids pass through,” said Weber.

Nebraska experts like Weber, worried about the effect of uranium, are beginning to study how and why this naturally occurring heavy metal is leaching into our groundwater.

They know that rocks inside Nebraska’s aquifers contain uranium naturally – but why is the radioactive material in these rocks seemingly escaping into the water supply at higher levels?

Weber and her team suspect nitrate, at levels near the 10-parts-per-million legal limit, releases uranium into the state’s groundwater, which provides drinking water for roughly 85% of Nebraskans.

As Flatwater Free Press previously reported, Nebraska’s median nitrate level has doubled since 1978, in part because of limited regulations from state and local governments. The problem is costing medium-sized cities and small towns millions for water treatment, and it’s driving farmers, researchers and policymakers to grasp for solutions.

These experts are also worried about the composite effect of uranium, other minerals and agrochemicals on human health. For the first time in Nebraska, they’re studying the link between these combined contaminants – including nitrate – and pediatric cancer.

High levels of uranium can enter the bloodstream and lead to kidney damage and other health problems, scientists believe. The EPA has set the maximum uranium level in drinking water at 30 parts per billion to prevent cancer risks potentially tied to chronic exposure to uranium.

Some two dozen community public water systems in Nebraska have detected uranium levels higher than that limit at least once since 2010, according to data provided by the Nebraska Department of Environment and Energy.

And the number of Nebraskans potentially affected by high uranium levels in drinking water may be higher than currently known. The state requires quarterly tests only for community public water systems that have already exceeded the EPA limit. Other community public water systems are tested far less often – sometimes only once every nine years.

There’s no testing requirement for private wells – wells not connected to a public water system. So rural Nebraskans who live outside city limits may have no idea if they’re drinking water that contains high uranium.

Due to patchy testing data, scientists say they don’t yet fully understand which parts of Nebraska are impacted by high uranium in their water.

“I don’t know if we know all of where it could be an issue and where it’s not,” Weber said.

How much uranium ends up in water hinges on several factors: geology, the water’s alkalinity, pH and what other chemicals exist in the water.

But the release of uranium into water is also tied to human activities, said Dan Snow, lab director of the UNL Water Center who has tested water samples for about three decades.

“We do have some hotspots in terms of uranium concentration in groundwater, and they tend to follow where we have a lot of irrigation, where we have a lot of fertilizer application,” he said.

Pumping water out of the ground for irrigation, drinking and other use can introduce oxygen and nitrate into the aquifer, Snow explained. Nitrate, largely from commercial fertilizers and manure, may then prompt the release of uranium by assisting in converting solid uranium to a state more poised to jump off the aquifer sediments and dissolve into water.

In a first-of-its-kind experiment, a research team led by Weber recently concluded that nitrate can, through a series of conversions, mobilize uranium in water. The research team is continuing to examine links between uranium and nitrate.

Much of the water around Hastings already contains high levels of nitrate. That nitrate could actually be the reason that the region is also now grappling with high uranium, Weber told Stange.

The uranium problem appears to be worst in areas surrounding the Republican River valley and parts of the Platte River valley in central and south-central Nebraska. Parts of northwest Nebraska have tested high for uranium as well.

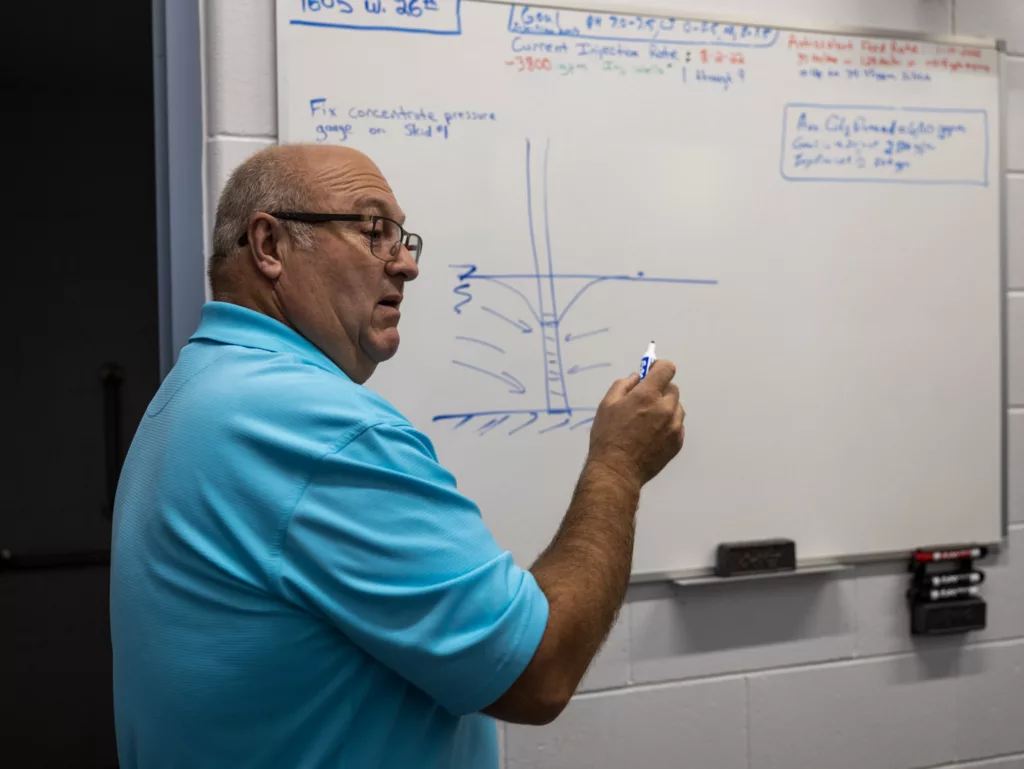

Sitting next to the Platte River, Grand Island has been grappling with uranium in its water for more than a decade.

Photo by Laura Beahm for Flatwater Free Press

In 2008, lab tests showed that a few municipal wells were exceeding the EPA limit for uranium. One jumped as high as 57 parts per billion, almost double the federal limit, the city’s water operator Lynn Mayhew recalled.

The city’s water system now treats three of its municipal wells with elevated uranium, sponging it out of the water supply so less of it ends up in residents’ tap water.

The city came to this solution after mulling installing an ion exchange or reverse osmosis plant. That would clean up the water but also create a need for waste disposal of dangerous concentrated uranium.

Photo by Laura Beahm for the Flatwater Free Press

Since uranium is constantly being released from rocks and silt, there’s no way to fix this problem once and forget it, Mayhew said. And there’s no cheap fix: It costs Grand Island roughly a million dollars each year to remove uranium from its water supply.

The water Grand Island serves its 53,000-odd residents has never exceeded the safety limit, thanks to its treatment plant and the blending of water from different wells, Mayhew said.

The city also supplies water to its neighbor, Alda, pop. 927, because the village doesn’t have the resources to create a treatment system of its own.

The presence of naturally occurring contaminants, including uranium, in Nebraska water is “all concerning in some ways” to Jesse Bell, University of Nebraska Medical Center professor and director of the Med Center’s water, climate and health program. It’s crucial to study these contaminants and agrichemicals, he said, because they may work together to affect Nebraskans’ health.

“There might be things working in tandem that we’re not even accounting for,” Bell said.

A group of University of Nebraska Medical Center researchers is studying the relationship between pediatric cancers and four contaminants, including uranium. They have collected water samples in the Upper Big Blue and Lower Elkhorn Natural Resources Districts, where pediatric cancer rates lead the state and are far higher than the national average.

In the meantime, UNL experts like Snow urge rural residents on domestic wells to get their water tested.

“Our regulatory levels are based on single exposure to a single contaminant. But now we have nitrate, we have uranium, we might have arsenic, we might have iron and manganese,” said Snow. “If there are kids that are consuming that well water, that seems like a big uncertainty right there that we really need to address.”

For Stange, the uranium test results have helped paint a clearer picture of what’s in the water he gives to Hastings residents. Some of that high uranium northwest of Hastings is moving towards the city as the groundwater flows southeast, brushing past the northern part of the city. Stange said his team avoids pulling water from that area.

“It hasn’t gone away. It’s still there,” he said. “We are going to continue to monitor. It’s a major step in understanding how to protect our water system.”

5 Comments

Thank you for this very informative article! Knew about the uranium levels being high here in Northeast Nebraska where I live,but I never associated it with being in the water.I thought it was more of a leaching gas infiltrating into older basements. IE Radon. I’ll be checking with my Rural water provider on this. I would imagine most people have no idea that it’s possible that they’re drinking contaminated water. Thank You very much!!!

I’ve been thinking about moving to McCook area from Iowa, now wondering if that is a wise move.

We are facing a calamity of nitrates from Farming fertilizer application.

Great article—-I predict many farming states in the same position.

There is a great documentary called Crying Earth Rise up about Uranium mining that may be of interest to many yet not exactly what this article is about but more about what’s happened in Crawford, NE and on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

My daughter has a ph.D from U-Texas Jackson School in hydro geology. She teaches at Central Michigan State, Mount Pleasant, MI. Does Nebraska want to work with her, researching this? They could always reach out to researchers or for consultations. Or are our politicians sweeping this to the back in favor of Rickett’s actions initiating a water war with neighboring states…while he makes rounds in rural Nebraska bad-mouthing Biden’s environmental programs?