In mid-July, a television station in India recounted the day the air conditioner died at a fast food restaurant 8,000 miles away.

The temperature had soared to 32 degrees Celsius — that’s 90 degrees Fahrenheit — inside a Burger King in Lincoln, Nebraska. Its manager had ended up dehydrated in the hospital, New Delhi’s News18 reported.

A top boss had called manager Rachael Flores a baby when she’d missed a meeting the day before hospital staff hooked her up to an IV, the story said.

A baby? Her employees thought she was a hero.

And when a fed-up Flores put in her two weeks’ notice, the entire morning crew — including her roommate Kylee Johnson — lined up to do the same.

Then the crew at the Havelock BK broadcast its departure on the fast food restaurant’s marquee, to their bosses, their customers and eventually the world:

WE ALL QUIT. SORRY FOR THE INCONVENIENCE.

It was a sign of the times. A message at the outset of what would come to be known as the Great Resignation.

“It was absolutely insane. We weren’t prepared for it to blow up. For how far across the world it went,” Johnson said nearly five months later.

The public exodus at the Home of the Whopper — in the middle of the country, in the middle of a pandemic — caught fire after Flores posted a photo of the sign on Facebook.

CNN and Newsweek. Breitbart and The Daily Mail. The Toronto Sun and the Teller Report. The Huffington Post and the Hindustani Times.

Johnson quit counting how many interview requests popped up in her social media feeds and LinkedIn profile. She stopped doing interviews when she reached double digits.

By then, readers around the country had rallied around the beleaguered manager and her employees for their decision to walk away. They tagged Johnson and Flores with their own signs. Shared their discontent with ill-tempered customers and insensitive bosses.

One publication put it this way: “Fast Food proletariat workers have renounced their Burger King.”

And Johnson agreed, telling reporters: “We became essential and then we weren’t treated as essential by upper management.”

Johnson is 24. She’s slight and soft spoken. She has big hair and a disarming smile. And she’s worked in the service industry since she was 16. Hy-Vee, Jimmy John’s, Scooter’s, Walmart, Ruby Tuesdays, a seven-month stint at Burger King, to help out her friend Flores during the height of Covid’s deadly winter.

It was a pit stop in her customer service career. One that would launch Johnson and the departing Burger King crew to better places, better bosses and better pay.

They would be far from alone.

AN EXODUS THAT PREDATES THE PANDEMIC

The disgruntled Lincoln Burger King employees proved to be near the leading edge of a tsunami smashing into the American labor market. A record 4.3 million U.S. workers left their jobs in August. In September, another record: 4.4 million. Since April? Roughly 20 million, a number nearly equal to the population of Florida.

Some retired early, done in by the pandemic and reluctant to return to the workplace after months at home. Some reinvented themselves and started their own businesses.

Still others began a round of job market musical chairs.

“We’re at a time in our job market right now where people see an opportunity to switch employment,” said Eric Thompson, director of the Bureau of Business Research at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. “Or they’re thinking about it because they see other people who have done it.”

For many of these 20 million, making a change is working in their favor, said Jim Begley, director of the William Brennan Institute for Labor Studies at the University of Nebraska Omaha.

Consider: Workers who have switched jobs have seen a 5.4% wage increase in the past 18 months, according to the Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. That pay bump is markedly better than the 3.5% increase for workers who stayed put.

The phenomena that played out at the Lincoln Burger King — and in recent strikes at John Deere and Kellogg’s — has a backdrop that predates the pandemic, he said.

Worker wages and benefits, especially in lower-income jobs, have stagnated in recent decades, Begley said.

“Workers are finally standing up and saying, ‘We’re not going to tolerate these conditions.’”

And they have leverage: There were 10.4 million open jobs nationally in September and only 6.5 million hires.

Which raises the question: “Is it a labor shortage or is it a wage shortage?” Begley said. “What all these anecdotes say to me is it’s a wage shortage.”

Or maybe a bit of both, UNL economist Thompson believes.

Labor force participation has fallen about 2% across the country this year, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

And the current exodus — Thompson calls it the “aftershock of the recession” — is reminiscent of the financial crisis of 2008, when the labor market shrunk by 1.7% and never fully bounced back.

“The rate may not go back to pre-pandemic levels,” Thompson said. “Probably some of it will be permanent.”

In this upside down job market — where Nebraska recently shattered a national record by recording all-time low 1.9% unemployment — businesses continue to sweeten the deal for service industry jobs with signing bonuses and higher pay.

Thompson compared preliminary federal data to prove the point: Hourly rates for the hospitality and leisure industry are up more than 7% in Nebraska and nearly 12% nationwide in the past year.

You can watch the pressure to lure those workers play out along Lincoln’s thoroughfares. In front of fast food joints, convenience stores, nursing homes, oil change shops. On marquees, placards and nylon flutter flags, all with a variation on the same theme: Please work here.

Begley sees hope in those signs. “The field is finally starting to level for the workers.”

And Johnson, who followed her manager out the Burger King door, sees breathing room.

If a job is a bad fit? There’s likely a better one waiting.

“There’s so many openings,” she said. “It does leave the door open.”

‘PEOPLE ARE STANDING UP FOR THEMSELVES’

All of the Burger King employees who left their jobs with a bang in July have opened new doors.

A few followed Johnson to Ruby Tuesday, where she’d kept her part-time job as a server and bartender after starting the day shift at Burger King last February.

Others found work as clerks or cooks at sit-down restaurants, hotels or convenience stores. Including Flores, who didn’t respond to interview requests. The majority went into something besides fast food, Johnson said.

“Almost everyone that I know that left has found better jobs making at least the same or more.”

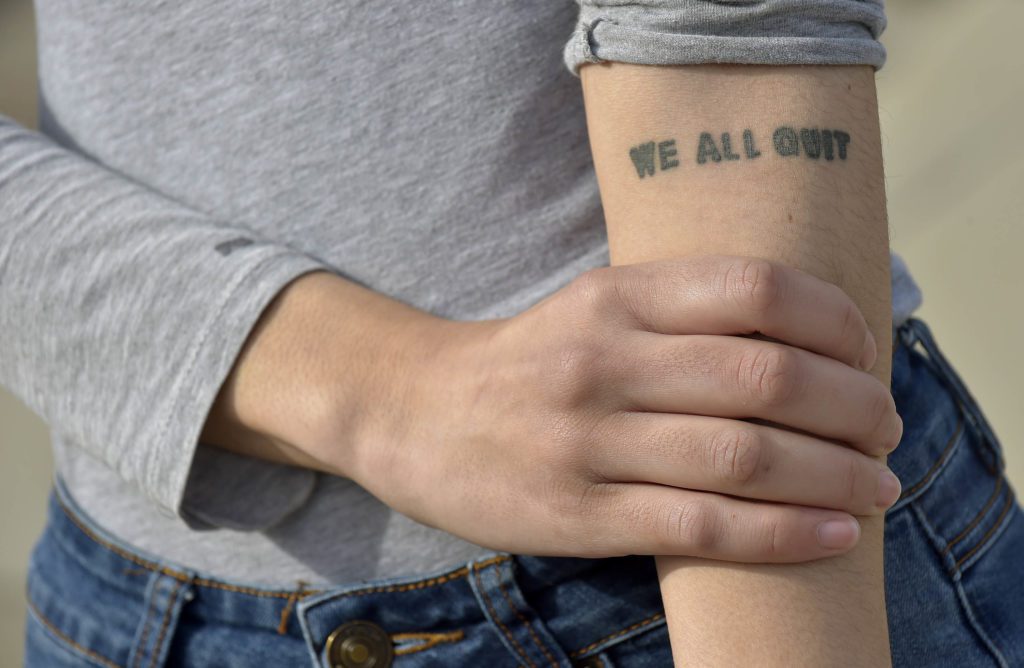

In mid-July, Johnson had three words inked across her left forearm: WE ALL QUIT.

The tattoo is a reminder of her worth.

“I was raised to give respect. But I was also taught that when you give respect you should be given respect back.”

Johnson was accustomed to getting grief from the public after eight years in the service industry. “In one ear, out the other.”

But knee-deep in a pandemic, sweating in a mask, running the drive-through, the front counter, filling orders — often without help — felt different.

“It was horrible. It was exhausting. Customers didn’t take any of that into account.”

And management wasn’t listening, either.

They wouldn’t fix the air conditioner properly, Johnson said, leaving the fry cooks and servers sweltering dangerously for several weeks. They wouldn’t, or couldn’t, remain at adequate staffing levels, leaving the staff constantly hurried and harried.

“Rachael was a fantastic manager,” she said. “But four or five people left and upper management had not tried to bring in anybody new.”

After employees publicly fled and the media barrage began, the Burger King Corporation deemed conditions at the Lincoln restaurant “not in line with our brand values.” Burger King Corporation didn’t answer requests for comment for this story.

Last week, Meridian Restaurants, a Utah-based company that owns 12 Burger Kings in Nebraska, including nine in Lincoln, declined to comment on changes made at the Havelock location where the sign now declares it’s “Grand Opening Week.”

On a sunny late November morning, Johnson posed for a portrait across the street from the Burger King on the north edge of town, a restaurant from which she says she’s now banned.

She doesn’t regret quitting, she said. For standing up for her boss and friend. For herself.

“I learned that this goes on everywhere and people are standing up for themselves and asking for better.”

Johnson is on track to graduate in April with a degree in business administration from Colorado Technical Institute.

She’s an entrepreneur, too, with a small business she calls Ky-Fro Photography, shooting family portraits and senior pictures.

Photography is her passion, she said, a skill she picked up in high school that led her to become the editor-in-chief of the Lincoln High Advocate, her school paper.

She’d love to grow her photography business.

“That would be amazing.”

In the meantime, she’s tending bar and taking orders at Ruby Tuesday, where a few of her loyal Burger King customers have followed her, trading in their paper-wrapped burgers for sit-down dinner specials.

And where for a few weeks this summer, in her Internet-inspired moment of pandemic history, two or three diners each night looked up from their menus, studied her face and asked:

Weren’t you that chick from Burger King?

10 Comments

Glad to see Cindy’s wonderful writing summaries returning!

Thank you for the update. I’m glad the former BK workers moved onward & upward!!

Great to be reading Cindy stories again. Thanks.

Darn you, CLK, you make me like human interest stories.

🙂 Congrats on the FFP article!

Love the stories from Flatwater Free Press!

I do too Susan. Worries about the demise of professional journalism are not premature but there is hope!

Glad to see that you weren’t gone for long! Scary things happening with nebraska newspapers and the eradication of journalism. Good first article – the story whithin the story. Thanks!

The company that manages this Burger King’s mission statement:

We are a restaurant management company operating Burger King, Chili’s Grill & Bar and El Pollo Loco. We have 126 locations across 10 states. Our Mission is LOVE! Our purpose is to make a positive impact in peoples lives; our team and our guests and communities.

We work every day to live our Mission of LOVE through our Core Values and a Culture of Accountability. We pursue accountability in a positive and principled manner, where self-accountability is taught and fostered. It may sound cliché, but for Meridian, we want leaders that LOVE what they do, LOVE their fellow team members and LOVE our guests! We feel the most powerful and important emotion in life is LOVE!

It’s always been this way, minimum wage jobs are for High School/College kids to obtain job skills, not a career, if she is 24 she show little ambition to further herself………….Did I mention that retired people take these jobs to remain active…………….

Great article Cindy. It’s fun to “see” you in print again.