Kids in the hallway smile more than they have in the past. Laughs are a little louder than they once were, teachers say. Student pride – and the graduation rate – are on the upswing at Santee’s public school. School leaders trace that success to a new effort to teach the tribe’s culture – the very thing that the education system, generations ago, banned Santee Dakota students from learning.

Now, a new cultural program immerses students in the tribe’s language, history and customs for as long as an hour each school day. The program, embraced by most teachers and students, has boosted student attendance and helped the iSanti Community School in Niobrara hit a perfect, 100% graduation rate two years running, school leaders say.

This move to embrace the Santee culture at the main school on the Santee Dakota Reservation hasn’t always gone smoothly. A recent teacher dust-up related to teaching Santee culture led to three suspensions and one teacher being banned from the reservation.

But school administrators, teachers, parents and kids interviewed say the cultural program is proving powerful. It’s improving student enthusiasm, they say. It’s improving student performance.

The proof of this follows fourth grader Wakiyan Curry home from school.

“He comes home and tells me what he learned in culture class,” said his mother, LeAnn RedOwl. “He doesn’t tell me about what he learned in math. He loves what he learns in culture.”

For more than a century, being Santee was something that authorities actively discouraged or outright banned.

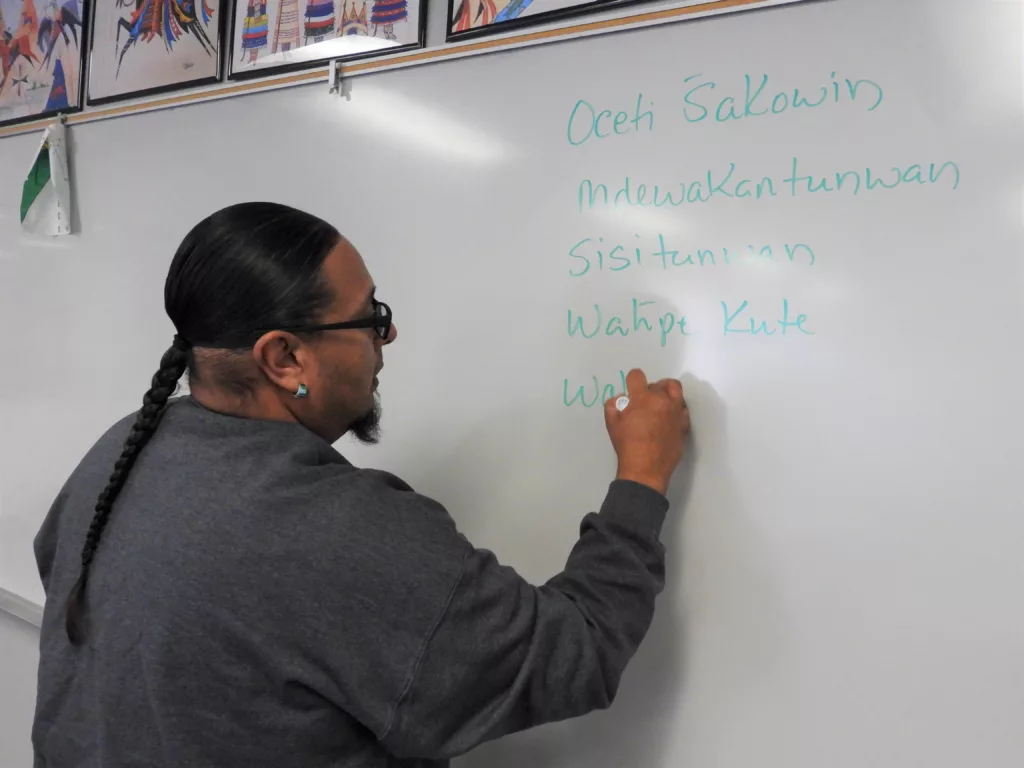

The school’s new program that daily teaches students of all ages the tribe’s language, custom and history has improved student enthusiasm and performance, say both school leaders and parents. Photo by Tim Trudell for the Flatwater Free Press

More than 150 years ago, federal agents ordered students at the Santee Normal Training School on the Santee Sioux reservation in Knox County to forget their native language, said Redwing Thomas, iSanti Community School’s culture director. They forbade the efforts of Episcopalian ministers running the school to balance education in English and Dakota.

“As long as (Santee students) are confined to their own language, they will be Indians,” Santee reservation agent Asa Janney told the Rev. Alfred Riggs, the founder of the Normal Training School. The federal government’s goal: Force assimilation, killing off the Indian inside students, who had already been ordered to cut their hair short and required to wear western clothing.

Compare that to today. Santee students – from preschoolers to high school seniors – take daily courses in Santee culture. They study the tribe’s traditional language, customs and written and oral history. The program, created by Thomas, encourages them to use the tribe’s traditional name, iSanti Dacotach, and to understand tribal heritage.

Elementary students learn Dakota words for months, seasons, flowers and numbers. High school students study the Dakota-US War of 1862, the mass hanging of Santee soldiers and the tribe’s forced exile from Minnesota and eventual relocation to northeast Nebraska.

Photo by Tim Trudell for the Flatwater Free Press

The cultural program embraces what’s iSanti, Thomas said. All of it.

“This is their program,” Thomas said of the students. “This is their story, and we get to help them on their journey.”

It’s a major development at one of the Nebraska Department of Education’s priority schools, which are considered among the state’s lowest-performing districts. Among Santee’s challenges: A historically low graduation rate, subpar national test results and spotty attendance.

The cultural program helps achieve the school’s goal of removing state oversight, said Jessica Crossman, principal at the junior-senior high school.

“The kids are really immersed into a great cultural program,” she said. “They’re willing to take risks in the classroom.”

Santee has achieved a perfect 100% graduation rate over the past two years, eclipsing the state’s goal of 80% for the school. The school is also on track to surpass the attendance goal of 88%, Crossman said.

Both Crossman and Cindy Nagel, the elementary principal, credit Thomas for creating and leading a program that has students engaged.

Thomas, in his fourth year at the school, previously taught Dakota as a language, while culture was intermittently discussed.

Now, it’s part of the daily curriculum. Preschool through middle school students spend 20 minutes a day on culture. It’s part of hour-long classes at the high school level.

“The kids are really excited. They’re not just learning a language, they’re applying it,” Nagel said.

Many of the school’s teachers incorporate language and culture in their daily lessons. Nephes Justo’s third grade class intertwines Dakota words with English, creating a Santee version of Spanglish.

Posters hung in the school’s hallways feature a Dakota word and its English version, often attached to artwork. There’s a mural featuring Ozuyapi (O-zoo-yaw-pi, meaning warrior) – the school’s mascot – and The Three Grandmothers, representing Lakota, Dakota and Nakota, the three nations of the Great Sioux Nation.

Inside Thomas’ classroom, students learn where the tribe originated – “Spirit Lake” about 90 miles north of the Twin Cities. The Santee students also learn the hardest parts of their history, like the Dakota-United States War of 1862.

“We have generational trauma. It’s not told as a story of sorrow or sadness, but one of strength,” he said. “We’ve survived so much. This is our story of how we persevere.”

That war started in southwest Minnesota after drought conditions and hunting restrictions placed on the Dakota left them hungry. Then the U.S. government didn’t deliver a promised annual stipend – compensation for surrendering land to the federal government – and instead rerouted the money to the Union Army during the Civil War.

Tribal leaders met with U.S. government officials and local businessmen and asked for credit, so tribal members could buy food and supplies for the impending frigid winter. They were denied. One local trader suggested that the Dakota people “eat grass.”

Days later, that trader was found dead, grass stuffed into his mouth.

He was among the first killed during the war, which lasted a little longer than a month before American soldiers outnumbered the Native fighters.

A few hundred white settlers and Native Americans were killed during the fighting.

After teaching the history, Thomas asks his students what caused the war.

“We have generational trauma. It’s not told as a story of sorrow or sadness, but one of strength,” said Redwing Thomas, director of the school’s cultural programs. “We’ve survived so much. This is our story of how we persevere.” Photo by Tim Trudell for the Flatwater Free Press

“One student blew me away with his answer. I was expecting ‘we hated them and they hated us,'” he said. “But, he simply said, ‘Misunderstanding each other.'”

Following their capture, a military tribunal hastily sentenced 307 Santee warriors to be executed. After President Abraham Lincoln oversaw a legal team that reviewed the trial transcripts, the president signed death warrants for 38.

On the day after Christmas 1862, thousands of local residents in Mankato, Minnesota, showed up to watch what’s still the largest mass execution in American history.

Some of those executed on the 360-degree scaffold built for the occasion may have participated in the war, while others were hanged for unrelated alleged crimes, like having a relationship with a white woman.

These men and two others later hanged became known as the Dakota 38+2, and have a special monument at the tribe’s veterans memorial on the western edge of town.

Another 1,500 or so non-combatants – elders, men, women and children – were transported to Fort Snelling, where they spent the following year in a prison camp, which some Santee refer to as a concentration camp.

The Santee captives were given scant food and few supplies.

They were separated, with men on one side of the prison camp at the bottom of a bluff near the Mississippi River and women and children on the other.

“They would sing traditional songs to each other, to let them know they were OK,” Thomas said. “The soldiers had no idea.”

Thomas tells his students of the women who survived that hellish year while doing everything they could to ensure their young children survived, too.

“If that baby died, you wouldn’t be here. My great-great-grandparents were there. I might not be here.”

The Santee Dakota were then forcibly moved from their homeland, relocated to the Crow Creek Agency in central South Dakota – and then forced to walk nearly 200 miles to the present-day Santee Reservation in northeast Nebraska. The walk is known as the Santee Dakota’s own Trail of Tears.

That’s a lot of history to take in, and the students soak it up, Thomas said. At the end of the lesson covering the war, students create a video, telling the story from their eyes.

While support for the cultural program is strong, a recent incident threatened to jeopardize the school’s progress.

A middle school teacher, a non-Native, allegedly told a student’s parents that Santee kids were stupid, and needed to learn core subjects, not culture, Thomas said.

The parents told Thomas, who reported it to school leaders.

The teacher then confronted Thomas, saying he didn’t say those words and demanding Thomas rescind his complaint, Thomas said. After Thomas refused, the teacher came to his classroom with another teacher and repeated his demand.

All three teachers were eventually suspended after several verbal altercations inside the school.

School leaders declined comment on the matter, calling it a personnel issue.

But the students, and then the tribe, did speak. Roughly 60 students staged a walkout one day to protest Thomas’ suspension. Thomas met them outside the Warrior Lodge, part of the tribe’s community center.

“I told them they needed to go back to school,” he said. “They needed to complete class. That’s how they win.”

Roughly 50 elders and parents, including tribal council and school board members, then met at the lodge, upset over the possible loss of Thomas, his four-person staff and the cultural program itself.

A few days later, Thomas was reinstated. The other teacher is no longer employed at the school.

The Santee Dakota Tribal Council then went even further, voting to ban the former teacher from the reservation, an act usually reserved for criminals. The council enacted the “Bad Man” clause of the 1868 Laramie Treaty.

The former teacher didn’t return several messages, emails and phone calls from the Flatwater Free Press requesting an interview.

Thomas returned to school, thanking the cultural program staff for, he says, “holding down the tipi” while he was suspended.

He hopes to soon prepare the staff to become tribally certified language instructors.

In the meantime, Santee kids continue to learn the language, culture and history of their ancestors inside their school – the first time this has happened in generations.

Nagel, the elementary school principal and a 7-year veteran of iSanti Community School, expects the program to grow.

Thomas says it has awakened something inside the students. He points at his T-shirt, emblazoned with the word, “Ozuyapi.”

He explains its significance.

“This word, at one time, was foreign to these kids,” Thomas said. “It even scared people to say it. But, now, you see it everywhere around school. Kids wear it with pride. ‘I’m an Ozuyapi. I’m a Warrior.’”

20 Comments

I applaud Redwing Thomas for his work in truly identifying and teaching his students the lessons they need to be successful in life. To stand up for what you believe, to stand up for your work and the students you serve…you bring honor to your community and your kids see that you value them. Thank you, Tim, for researching this story and bringing it to us. So much of education is meeting youth where they are and providing them the inspiration they need to realize who they are, where they come from and that each one of us brings value to our community and world. This was a great story to start my day….thank you, Tim and Redwing.

What a wonderful article…Why man thinks we all have to be the same… We all should embrace our heritage.

Tell me more! In addition to the critical history lessons and language, I’d also love to know more examples of the kinds of cultural information students are being exposed to? Are the parents or community members also involved? It strikes me that in many families, everyone might need a refresher on cultural practices that were actively discouraged, if not destroyed, over the years. Are similar things happening on Nebraska’s other reservations?

Thank you for this awesome piece. It’s an example of the kind of stories I look forward to reading on FFP.

What a wonderful article!! What beautiful history, of resilience, leadership, & hardship & pride. You are STILL here!!

Especially The 7th generation of which the ancestors are so very proud of. Being from Minnesota, this history & other Native American history should be taught in ALL schools. It is our county’s History and bears the road to healing when it is acknowledged and honored. History such as this, us not taught so well in our normal school settings. It is much more relevant then Europeans coming over and being settled.

I now want to visit the original place of origin 90 miles north in mn and Mankato. Kudos to your great nation ! New generation Warriors arising!

What a wonderful article!! What beautiful history, of resilience, leadership, & hardship & pride. You are STILL here!!

Especially The 7th generation of which the ancestors are so very proud of. Being from Minnesota, this history & other Native American history should be taught in ALL schools. It is our county’s History and bears the road to healing when it is acknowledged and honored. History such as this, is not taught so well in our normal school settings. It is much more relevant then Europeans coming over and being settled.

I now want to visit the original place of origin 90 miles north in mn and Mankato. Kudos to your great nation ! New generation Warriors arising!

Thanks for this program and this story.

Excellent article. Thank you so much for bringing this story to light.

Fantastic work and results ~~~ While living/working in northwest Alaska had the opportunity to have traveled and worked with a number of villages and tribal corporations, and the loss of culture (including history) and language was/is a big concern. In my area, along the coast of northwest Alaska the culture ~ Iñupiat and the language is Iñupiaq, which now Rosetta Stone has an application available… The folks in St Lawrence Island are Yupik (Siberian Yupik), and for them the loss of culture and language is also a concern, but most are fluent ~~~ for my meetings and project presentations to the Native Corporation and Elders had a Yupik interpreter ~so I thought this was great. Any who, keep up the fantastic work… and not sure if it would be a possibility = Rosetta Stone has a ” Rosetta Stone Endangered Language Program” ~ cheers from my side

About time! Thank you Redwing Thomas.

It a beautiful way to bring the culture in their life, ..

Masi!(Thanks!) for this article. I’m glad

that Native Pride is producing such

great results. I’m an honorary Chinook

Tribal Artist & I promote them, always.

Thank you Rewing Thomas for being a positive role model and teaching Santee Dakota language and Dakota history. Native students need to see more Native men doing positive things.

Very nice. Learn your original language and culture, history, and heritage.

Very nice to learn your own history, heritage, culture, and language. Knowledge is important. Keep up the good work.

Keep it up. The Constitution is for all Natives and we need to stand up for OUR RIGHTS!

I’m so proud of you all. The love you put forth is setting an example of how powerful and healing our language and culture can be. Thank you Redwing.

I’m so proud of you all. The love you put forth is setting an example of how powerful and healing our language and culture can be. Thank you Redwing.

May I share this on Facebook and privately to people I know who will be interested (and ENCOURAGED) greatly by this?

I am grateful to all of you that make these programs work. You are inspirational. Keep going!

ABSOLUTELY AWESOME incredible!!! I hope it spreads to all first nation schools!! ITS ABOUT DAM TIME!! Yes sir you definitely are a warrior Redwing Thomas thank you