The voices ascended as the harmonies multiplied until they threatened to pull the song apart. Then something shifted. A few sang higher. Others descended. A chord and melody emerged.

With the sweep of his hand, the River City Mixed Chorus’s artistic director Barron Breland halted the cacophony.

“Sopranos, we’ve got some really lackadaisical vowels,” he said from the podium inside a rehearsal space at First United Methodist Church near 72nd and Cass streets.

A few members laughed. They’re used to how the director communicates, one of many patterns they’ve come to expect over the years – a song’s jittery evolution, show-week tweaks, the quick way new members become family.

At 40 years old, the River City Mixed Chorus is one of Omaha’s oldest and largest LGBTQ+ organizations. In that time, it witnessed a lot of change, captured in documents it donated to the Queer Omaha Archives at the University of Nebraska at Omaha library.

Members mourned during the HIV/AIDS crisis, celebrated during the legalization of same-sex marriage and showed solidarity after violent attacks. Locally they’ve watched queer groups start then shutter, and felt acceptance for their community ebb and flow.

Along the way the chorus’s membership swelled from nine to nearly 200, and it went from performing in bars to the city’s largest stages. Its budget, which once could have fit in a slim wallet, now includes an endowment, scholarships and corporate donations.

What hasn’t changed, members say, is the need it fills.

When Mark Van Kekerix came out at 39 years old he needed a community. Singing in the chorus sounded fun, but it was the people who’ve kept him coming back since joining in 2006.

“It was fun to find people just like me,” he said. “People that go to church, people that have kids, people just trying to figure out how to make enough money to survive. That was the part that really made me stick with it.”

‘There’s gay choruses?’

In 1984 Michael Jackson dominated the charts, Apple released the Macintosh computer and six Omahans drove to Des Moines to see the Twin Cities Men’s Chorus.

In the van, Gary Emenitove was full of curiosity.

“There’s gay choruses?” Emenitove, in an interview years later, recalled thinking after learning of the chorus.

The first groups started in the 1970s, years after the Stonewall riots ignited the movement for LGBTQ+ rights. In cities like San Francisco, New York and Chicago, the choruses combined arts and activism that hooked people like Emenitove.

He and his friends wondered: “Can we start a chorus in little Omaha?”

Within a year, the group had meetings with typed minutes, bylaws and established themselves as a nonprofit.

“The River City Mixed Chorus is a volunteer community chorus, organized to provide the opportunity for gay/lesbian and gay/lesbian-sensitive men and women to sing together,” reads the statement of its purpose, adopted Aug. 5, 1984. “The primary purpose of the chorus is musical excellence.”

By winter, the group, eight men and one woman, debuted at The Max in downtown Omaha with a holiday concert.

In the early years, many kept their identity quiet. People omitted their names from some of the chorus’s first programs for fear of losing their jobs or other consequences.

The chorus’s archives capture protests to the showing of a movie about gay politician Harvey Milk in 1985. Police brutality against gay men was a primary concern raised by the Omaha Gay Freedom League in its inaugural newsletter in August 1972. The 1993 killing of Brandon Teena, a transgender man, in Humboldt, Nebraska, became a defining LGBTQ+ hate crime.

Pushback came subtly too. In 1990 Omaha Mayor PJ Morgan proclaimed a week in late June, “Understanding Our Differences: Respect for All Persons Week” instead of “Gay/Lesbian Pride Week.” Sometimes that attitude still feels relevant, said Breland, the chorus’s artistic director.

“That’s sort of the most Omaha, Nebraska, way to do it where you’re not for or against it,” he said. “You’re just sort of letting people do their own thing.”

‘One of the best examples of humanity’

The River City Mixed Chorus quickly found its place in Omaha. It had write ups in the state’s queer newspapers and the Omaha World-Herald. The Union Pacific Foundation gave $375 for the group’s 1987-88 season, according to its archival material. Stan Brown, a longtime member and past president, couldn’t remember any protests against them.

Drama arose from time to time – board members resigning, disagreements over musical direction, complaints about concert attire – but members were more excited by what they were building.

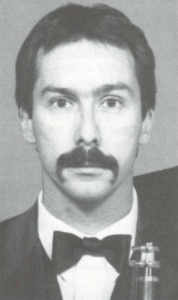

In 1985, music director John Zeigler wrote a letter to a national gay newspaper about its skimpy Midwest coverage. In the nine years he’d lived in Omaha, Zeigler was proud of the growth he’d seen in its gay community.

“I’m well aware that there is a higher concentration of subscribers on the two coasts,” he wrote the paper. “I hope however that you will continue to include items on gay life in other parts of the country.”

One of the group’s greatest struggles came just a year later when Zeigler died of AIDS. By 1987 about 48,000 people with the autoimmune disease had died. By the end of the millennium it was about half-a-million.

Zeigler’s illness was made public when a friend wrote a letter to the Omaha World-Herald, saying he thought it was horrible Zeigler’s death was “being whispered about.”

“John Zeigler was one of the best examples of humanity. He was talented, smart, friendly, sensitive and loving,” David Hagy wrote then. “He was gay, and he died of AIDS. He died of a disease unjustly shrouded in shame.”

Some wrote letters to the paper in disagreement, quoting Bible verses and writing that Zeigler’s death was a consequence for his immoral behavior.

Others showed support. A fund started in Zeigler’s memory helped buy equipment and pay researchers at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in the early days of the crisis, said Susan Swindells, a UNMC professor and AIDS researcher.

The chorus honored Zeigler and others through music and by contributing to the AIDS Memorial Quilt. The project, started in 1985, today weighs 54 tons and could cover eight city blocks in Manhattan.

Support also came from Philadelphia, San Diego, Baltimore, San Francisco, Detroit, New Orleans, Denver, Vancouver and Portland.

“Although I didn’t know John. I share your sense of loss,” wrote a member of the Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C. in a sympathy card. “I’m sure that he left a musical legacy that will sustain his memory for many years to come.”

‘We are making a mark’

As the chorus charted its 40th year, it searched for songs to tell its story of struggle, success and resilience. In April it sang “Survivors,” a lament for the HIV/AIDS crisis, while images of patients and activists were projected around them.

It was a reminder of how tragedy necessitates solidarity.

In that way, the history of the River City Mixed Chorus, and of Omaha’s LGBTQ+ community, mirrors the nation’s queer community, said Amy Schindler, UNO’s director of archives and special collections, who oversees the Queer Omaha Archives.

The archive tells a typical story of the last half-century in queer history in a Midwest city. Change often flowed from the coasts. Protests were usually local responses to national events. It’s groups like the River City Mixed Chorus, built by and for queer Omahans, that set their story apart.

“‘That is our place,’” Schindler said of the pride people felt toward the chorus. “‘We are making a mark. We are gathering. We are building a culture.’”

In June 2015, the day after the U.S. Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage, the River City Mixed Chorus took the stage at the Holland Performing Arts Center for the first time in its history and performed feel-good Broadway music.

The next June they scrambled to include a song to honor the 49 people shot and killed at Pulse, an LGBTQ+ nightclub in Orlando.

“When life knocks us down, we get up, we keep going, we rise again,” Breland wrote in the program then.

‘I totally let my guard down’

As society became more accepting, many of Omaha’s queer social groups, churches, bars and events began to disappear.

Some like River City Mixed survived.

“It is not one thing,” Schindler speculated as to why the chorus has lasted. “It fills a lot of those creative and social needs. But also, it brings joy and happiness. That’s one of the things music and the arts do. And we need more of that, right?”

Van Kekerix said the chorus has worked to bring in younger and more diverse singers. Scholarships help reduce membership costs. It worked so well it affected the dynamics of the choir – they solved the gap in sopranos and altos but exposed new needs in the tenor section.

Their stages have also grown from small bars and churches to the Holland Center and the Orpheum Theater – two of the only venues that can fit the group and its audience.

In the early days the budget relied on fundraisers – selling homemade cookbooks, hosting architecture tours, organizing garage sales. Now sponsorships from the Omaha Public Power District, Mutual of Omaha and Walmart play a big role.

Some things don’t change. After wins like the right to same-sex marriage, the debate has shifted to transgender people and drag performances. While no one’s omitting their name from the program anymore, plenty change their clothes and put on or take off makeup to become the person in choir they believe they can’t be elsewhere.

Recently some members of the choir’s cars were broken into outside the rehearsal space. They didn’t know if they were targeted, but the choir hired security to monitor the lot just in case.

Inside they practice songs like “Testimony” that begins with self hating, suicidal lyrics inspired by interviews done with It Gets Better, an LGBTQ+ nonprofit.

“Every night I ask God to end my life,” the lyrics read. “I am an abomination.”

By the time the singers reach the end, the lyrics have transitioned.

“I was more loved than I dared to know. There were open arms I could not see. And when I die, and when it’s my time to go, I want to come back as me.”

“‘Testimony,’ is me,” Joyce McVicker said. “It almost makes me cry every time.”

Growing up, no one talked about being queer, said McVicker, now 70. When she started living as a lesbian, her friends suggested she join the River City Mixed Chorus. That felt a little too open, but she went to a concert anyway. She loved it and joined in 2013. For the first time it felt like she could be herself.

The group has become a family for her and its younger members continue to inspire her.

For Kaitryn Williams, singing alongside others, especially older queer people, has made Omaha feel like home. While growing up in Cedar Rapids, Williams didn’t have queer role models. When they arrived at Creighton University, they struggled. Then they found the choir.

“I can not think about who I am or how who I am is different from everyone else,” said Williams, 25. “I can talk openly about my life, my queerness and my relationship without having to think twice about it. I totally let my guard down in a way that I literally cannot anywhere else.”

5 Comments

This is an excellent article! I’m not originally from Omaha and had no idea of the long and wonderful history of the River City Mixed Chorus. I teared up a few times just reading this. My best friend since we were 5 years old is gay. He’s a free-lance writer for a large company that textbook material. He still fears losing contracts because of who he is.

Wonderful article about love and acceptance. Thank you so much for sharing.

A pleasant surprise I knew nothing about. I need to figure out why?

Great story!

As a former member of River City Mixed Chorus, I feel proud about the chorus thriving after many lean years. John Ziegler was very talented and capable man. When he died the chorus had a difficult time finding someone to lead them. I’m so happy they are still around and better than ever.