Nearly 94,000 rabid Dallas Cowboys fans were causing a triple-digit decibel roar across 3 million square feet of aluminum and steel.

The squad once widely known as America’s Team was hosting the Green Bay Packers in what the Dallas faithful hoped would be the start of a playoff run to the team’s first Super Bowl since 1995.

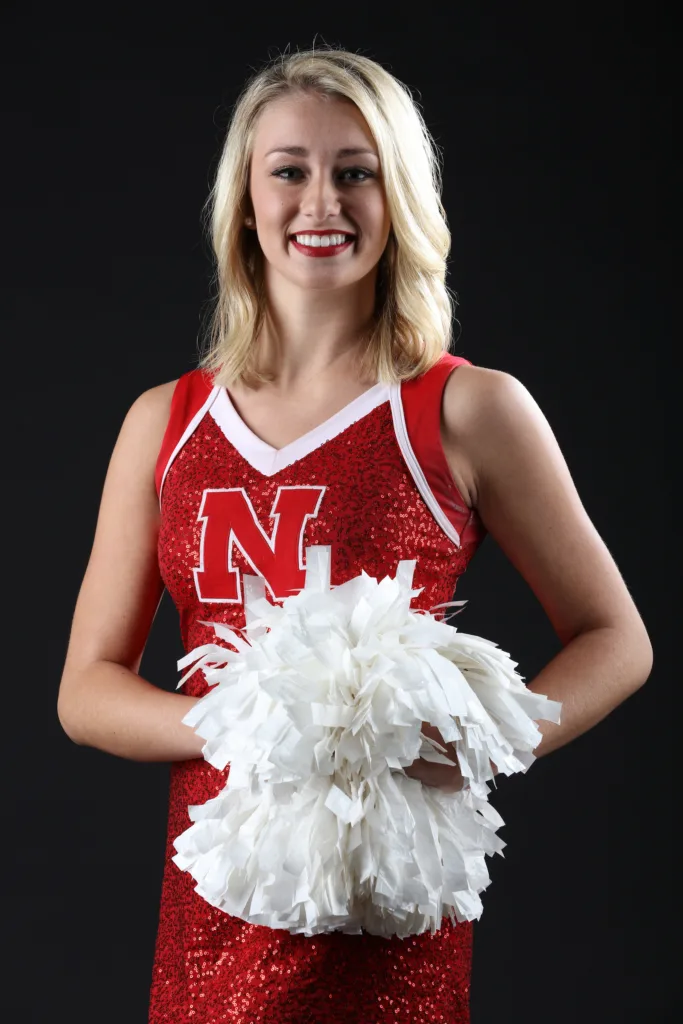

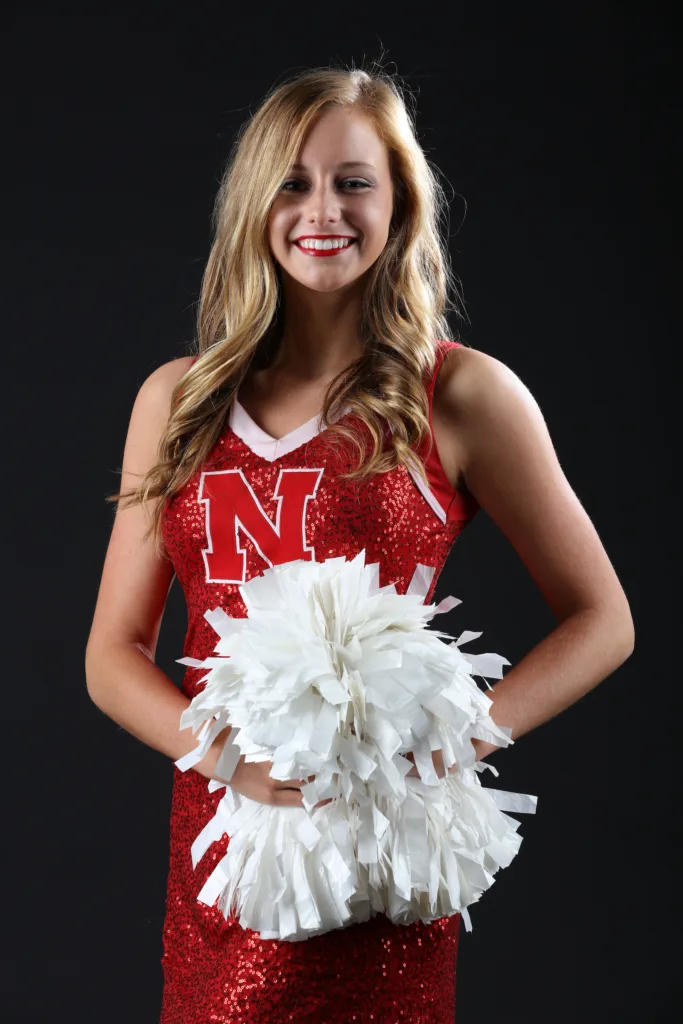

Claire Wolford, Kelcey Wetterberg and 34 other women stepped from the stadium’s tunnel into the spotlight. Deep, drawn-out breaths guised beneath unwavering smiles.

“And now, ladies and gentlemen, here they are, America’s Sweethearts, often imitated, never equal, internationally acclaimed,” public address announcer Jeff Kovarsky built up, “your Dallas Cowboys cheerleaders!”

Showtime.

“You’re nervous, you’re excited, you don’t want to mess up,” said Wolford, who just finished her fourth season on the squad and her first as a co-captain. “But you’re so proud to just have made it that far and to walk out on that field. … It is just the most incredible feeling in the world and it really doesn’t get old.”

Wetterberg and Wolford are leaders on perhaps the most iconic cheerleading squad in the world – positions that require serious sacrifice and offer little financial reward. They’re also Nebraska natives.

“I definitely didn’t think I’d be able to do it. … I just didn’t think someone like me from a small town in Nebraska could be here,” said Wetterberg, a Norfolk native and co-captain.

The two are far from the first Nebraskans to perform as Dallas Cowboys cheerleaders.

That journey can be traced back to 1960 and Cowboys general manager Tex Schramm, a former CBS television executive who wanted more entertainment in football. Schramm hired professional models with little dance experience as cheerleaders – a disastrous decision further exacerbated by the Texas heat.

The team made several pivotal changes in 1972 while trying to use football and the spectacle to renovate the city’s reputation following the Kennedy assassination.

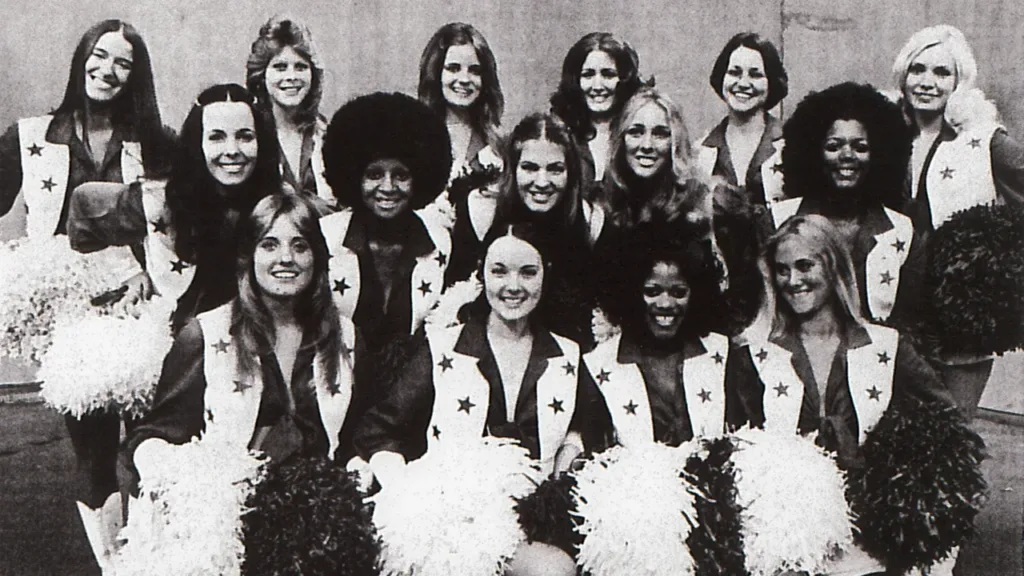

Director of cheerleaders Dee Brock enlisted designer Paula Van Wagoner to create the now-iconic uniform: blue halter tops, tied at the waist, with white hot pants and white vinyl go-go boots. Pirouettes and serious dancing replaced cheers and chants. Sixty auditioned, hoping to join this new era of cheerleading.

Seven made the cut.

Beverly Flower Gallagher had just moved from Omaha and was competing at the Miss Texas Universe pageant when she saw an advertisement for tryouts. The former high school cheerleader nailed her audition and made it onto the 1973 team. (Correction: This article incorrectly stated where Beverly Flower Gallagher attended high school.)

She cheered in front of over 100,000 people and, a week later, performed while the Cowboys won Super Bowl X.

Gallagher was also there during a Monday Night Football game against the Kansas City Chiefs on Nov. 10, 1975. With 5:03 left in the third quarter, the camera cut to Gwenda Swearengin. The second-year cheerleader held her gaze, rustled her pom poms over her cascading dirty blonde hair and shuttered her right eye. It’s known in Cowboy cheerleading lore as “the wink.”

“Obviously we don’t put the girls in those uniforms to hide anything,” Dallas dance director Suzanne Mitchell told Sports Illustrated in 1978. “Sports has always had a very clean, almost Puritanical aspect about it, but by the same token, sex is a very important part of our lives. What we’ve done is combine the two.”

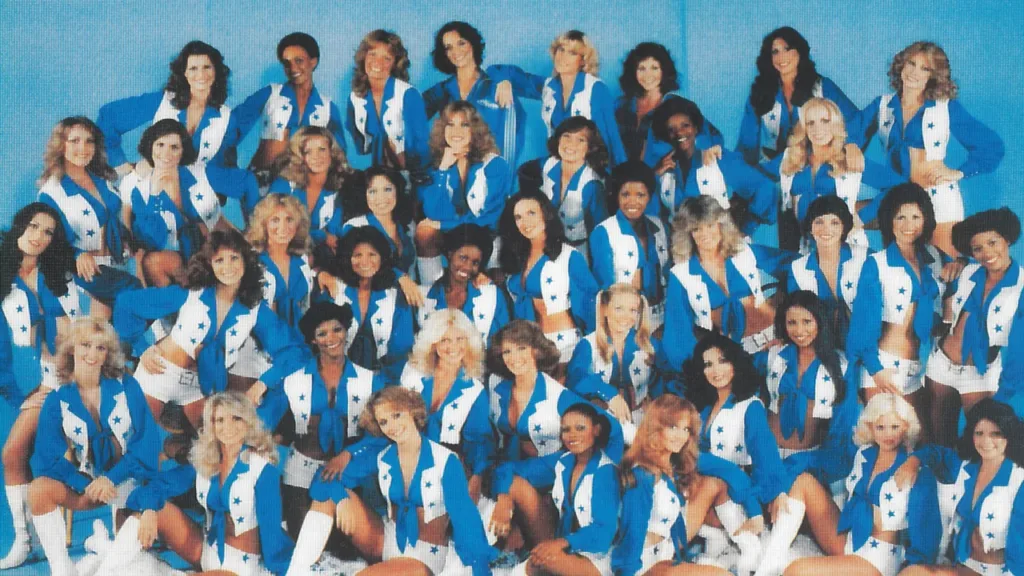

The squad became a phenomenon. By the time Bellevue High School graduate Tami Barber joined in 1977, the team was 32 members and breaking barriers. They appeared on game shows, in sitcoms and movies and went overseas on USO tours. Country Music Television aired a reality show, “Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders: Making The Team,” for 16 seasons.

Ambitious dancers from everywhere aimed for Dallas. Tens of thousands auditioned over the years, and a few Nebraskans stood out along the way.

Omaha Marian High School graduate Micaela Johnson performed on the team in the early 2000s. Nebraska native and graduate Carmen Butler was a Cowboys cheerleader for three years.

NU Spirit Squad head coach Erynn Butzke, who performed with the Denver Broncos before returning to her alma mater to coach in 2011, acknowledged the uniqueness of the Cowboys cheerleaders.

“Their uniform, their style of performance is all iconic …” Butzke said, noting that the Dallas cheerleader uniforms hang in the Smithsonian. “And it takes so much to earn the opportunity to wear that uniform that people put it on a pedestal because it’s so recognizable.”

Butzke met Wetterberg when the current Cowboys cheerleader was in eighth grade. Wetterberg’s family had moved to Omaha from Norfolk and she struggled to find a studio she liked. Eventually she connected with Butzke, who reignited her love for dance and kept her from pursuing volleyball instead.

“What really kept me going was the mix between athleticism, pushing your body in an athletic way, and also the artistry of it,” Wetterberg said. “Just being athletic while still making it look pretty and telling a story.”

Upon graduating from Millard West, Wetterberg went to Arizona State to dance competitively. The team won a national gold in jazz dance during her sophomore year.

Wetterberg then came home to pursue another dream. As a child, she admired the nurses while in the hospital waiting for her older sister to give birth. She returned to study nursing at the University of Nebraska Medical Center and perform with the Scarlets dance team.

At that same time, Wolford enrolled at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The Lincoln native fell in love with dancing at 2. She staged living-room dance shows years before she danced at Lincoln Southwest. Like Wetterberg, Wolford almost left dance in middle school. But volleyball didn’t offer the same therapeutic escapism and freedom of expression.

“When I’m on the stage I feel like I come to life and it brings out a different side of me,” she said. “That’s what made me fall in love with all that.”

The two bonded during their shared time on the Scarlets. When Wolford wanted to dance competitively, Wetterberg suggested Arizona State, where Wolford became choreography captain.

Meanwhile, Wetterberg’s college career was weeks from ending at graduation. She called Butzke, wanting advice on what to do next.

For most dancers, college is the end of the line. Few make it professionally.

Wetterberg mentioned her admiration for the Cowboys cheerleaders, but didn’t think she was good enough. Butzke convinced her otherwise.

In 2019 she and more than 300 other hopefuls showed up in Dallas for the cattle call preliminary audition. Each hoped a 90-second dance would be enough to convince a panel of judges to get them a second audition. Seeing all those talented women walking into AT&T Stadium made her want to turn around.

“I was pretty terrified,” she said.

But the panel kept calling her number. The entire audition process lasted from May to August. She studied for her nursing boards during the day and practiced cheering at nights.

It was emotionally, mentally and physically taxing but worth it, she said. She urged her old teammate to join her in Dallas.

“I just wanted her next to me to be here and do this with me,” Wetterberg said. “The way that it changed me as a human being even in my first year, I wanted Claire to come here because I know that we’re very similar and I just knew that she would be a perfect fit for this team.”

Wolford auditioned in 2020. COVID-19 caused auditions to go virtual. Over 1,500 submitted audition tapes. Within weeks, Wolford learned she made the team.

“It was very challenging because everybody is at such a high caliber,” she said. “You’re trying to kind of dance for your life every night.”

Being a member of the iconic team requires serious sacrifice. The cheerleaders make only $150 per home game – up from the $15 per game Gallagher and Barber were paid 50 years ago.

Excluding game days, they practice three hours each weekday evening to accommodate their day jobs. Wolford works as a Pilates instructor and Wetterberg has her nursing career.

They also earn money from special appearances, attending events on behalf of the team for undisclosed fees.

Most of the NFL’s 32 teams have cheerleaders. Ten of them have faced lawsuits from cheerleaders alleging wage theft, harassment, unsafe working conditions or discrimination. In 2022, the Cowboys made a confidential $2.4 million settlement with four cheerleaders after they accused a former senior team executive of voyeurism at a 2015 team event, according to reports.

Despite hectic schedules, exhaustion and low compensation, both women say being a Dallas Cowboys cheerleader is a dream come true.

Butzke isn’t surprised Wolford and Wetterberg reached the pinnacle of the sport. They’re two of the best dancers she’s ever worked with, she said.

“I know that they’re an inspiration to a lot of dancers, and I think sometimes you just need to hear that you can do it to inspire others,” Butzke said. “They’re amazing people and I love that they stay connected to their Nebraska roots.”

Both Nebraskans, now veterans on the 36-person squad, are now part of the leadership group. They run practices when needed and make sure the team is ready for each performance. Wetterberg made the ProBowl as a cheerleader last year, a distinction voted on by coaches and peers.

They credit their home state with laying the foundation for their successes.

“Growing up in Nebraska, you’re taught really great values like family and faith and everyone has a reputation for working hard and being down-to-Earth, really humble people,” Wolford said. “We’d both want to share our love for Nebraska and the Scarlets and how that shaped where we are today. We’re very proud of where we come from.”

The Flatwater Free Press is Nebraska’s first independent, nonprofit newsroom focused on investigations and feature stories that matter.