In the summer of 1978, Allen Wilke slammed the brakes.

He did this often. A true plantsman, he observed everything but the road itself. He would spy a flowering prickly pear in the ditch, a wild grapevine, and double back without warning. He would take a photo, a cutting, shuffle back to his gutted cargo van and carry on. He wore dusty chinos and a pocket protector, and often sent his son and daughter – half-asleep in his jerry rigged backseat – tumbling forward with the rest of his luggage.

This time, the plantsman was alone. He was puttering through the Sandhills on Highway 91, a mile west of Taylor, when a tall and skinny evergreen — not unlike an Italian Cypress, he thought — punctured his periphery. He slammed the brakes. He doubled back. And like he had so many times before, and would so many times again, the proprietor of the Wilke Landscape Center in Columbus knocked on a stranger’s door.

“Would you mind?”

The rancher led the plantsman to that eastern redcedar on the hill, rising like a steeple behind so many snot-nosed cattle feeding at the trough. To Marlin Britton, a lifelong Sandhiller, the tree was markable if not re-markable. But to Wilke, now scrambling up the bank for a closer look, it was a perfect fit for Nebraska’s landscaping industry. He took a few 10-inch cuttings, shook Britton’s hand and hit the road.

By the early 1980s, Wilke began retailing a new variety of tree he called the “Taylor Juniper,” a play on both its origins and its naturally tailored appearance. But “it wasn’t his forte to be marketing a new plant to the world,” his son Evan says. On February 4, 1992, the curious plantsman relinquished his business interests in the Taylor Juniper to the Nebraska Statewide Arboretum. He died one month later, just days after the arboretum formally introduced his beloved tree variety to every licensed nursery in the state.

Thirty years after its commercial introduction, the Taylor Juniper is now ubiquitous across Nebraska, from the town square in Taylor to the capitol grounds in Lincoln; the gates of Wyuka Cemetery to The Gardens at Yanney Park; the track at Hastings College to the belltower at the University of Nebraska at Kearney. The trees fill the nurseries come spring and sell out come fall – each a perfect clone of that single mother tree in Britton’s pasture.

“Every once in a while, I’ll drive past one and it’s like, ‘Oh! There’s one of dad’s trees!’” says Alan Britton, Marlin’s son. “I don’t know how to describe it, but there is an emotional tingle.”

Taylor, pop. 140, is today known for two things: The Villagers, a series of plywood cutouts depicting its earliest citizens in grayscale; and the “Taylor Juniper,” now garnishing every other property in town. The visitor center. The historical museum. The old library. The new library. The football field. The campground. Backyards. Front yards. Old homes. New Homes. And more.

“Now when you go by Taylor, they’re everywhere,” says Colt Kraus, former chair of the Taylor Community Arboretum. “Because what else do we have?”

Shortly after Wilke took his inaugural cuttings, Alan Britton – knowing his father’s cattle often rubbed against it – fenced off the mother tree. But in 1985, Britton retired. The new owners took the fence down. The cattle returned. The tree’s needles dropped. The drought settled in. And finally, in 2012, she died, boxed out by a gang of younger cedars. Today, her own skeleton marks the grave, standing like one more Villager, drained of color, on the hill.

“When I saw that I felt sad,” Britton says. “But my understanding is that all of the trees you see now are not offspring of that tree. They are that tree.”

As Wilke knew from the beginning, seeds harvested from the mother tree weren’t likely to bear an exact resemblance. Cuttings, on the other hand, carry the same genetic makeup. Whether he rooted them or grafted them, he could potentially make a perfect facsimile: tall, straight as an arrow and rushing skyward.

He planted those first cuttings in the dirt. A few of them took, slowly. The others shriveled away. Discouraged by the results, he called a man named Don Cross who operated a wholesale nursery in Minnesota, one of only a few still grafting trees in the Midwest.

Cross admired the plantsman’s curiosity. He agreed to help, with one caveat: if the grafts succeeded, Cross Nursery could add the Taylor Juniper to its catalog, royalty free.

“Soon enough we were grafting 100 a year. Then 200. Then 300. Then 500. Now we grow over 1,000 a year,” Cross says.

They shipped them back to Wilke in Columbus. To the statewide arboretum in Lincoln. To Connecticut and Oklahoma and so many nurseries and retail centers in between.

“Today it’s Cross Nursery’s signature tree.”

And every year, roughly 100 are sent to the Sandhills, their ancestral homeland. Marah Sandoz, the artist behind the Villagers, now sells them for $25 in her gallery on the square.

But the Taylor Juniper was hardly an instant bestseller. By the early 2000s, Wilke’s new tree variety had nearly disappeared from the marketplace.

“I called around, tried to find out,“ says Bob Henrickson, the statewide arboretum’s assistant director. “None of the Nebraska nurseries were carrying it, and most of them hadn’t even heard of it.”

So the arboretum tried again, boosting the profile of the Taylor Juniper by selecting it as one its “Great Plants for the Great Plains” program in 2003.

“I’m pretty proud of that,” Henrickson says. “If I hadn’t done anything, I think it would still be lost in obscurity.”

In the summer of 2009, Taylor followed suit. Armed with a $5,000 grant from the statewide arboretum, a local committee revamped the village park. It planted sixty new trees representing 30 different species, installed identification tags and memorial bricks and two new welcome signs. The whole town is now considered a “Landscape Steward” site by the statewide arboretum and boasts well over 100 Taylor Junipers, its cornerstone tree.

“All of the other small towns around Taylor have things that anchor them to existence,” Kraus says. “Taylor needs that, too.”

***

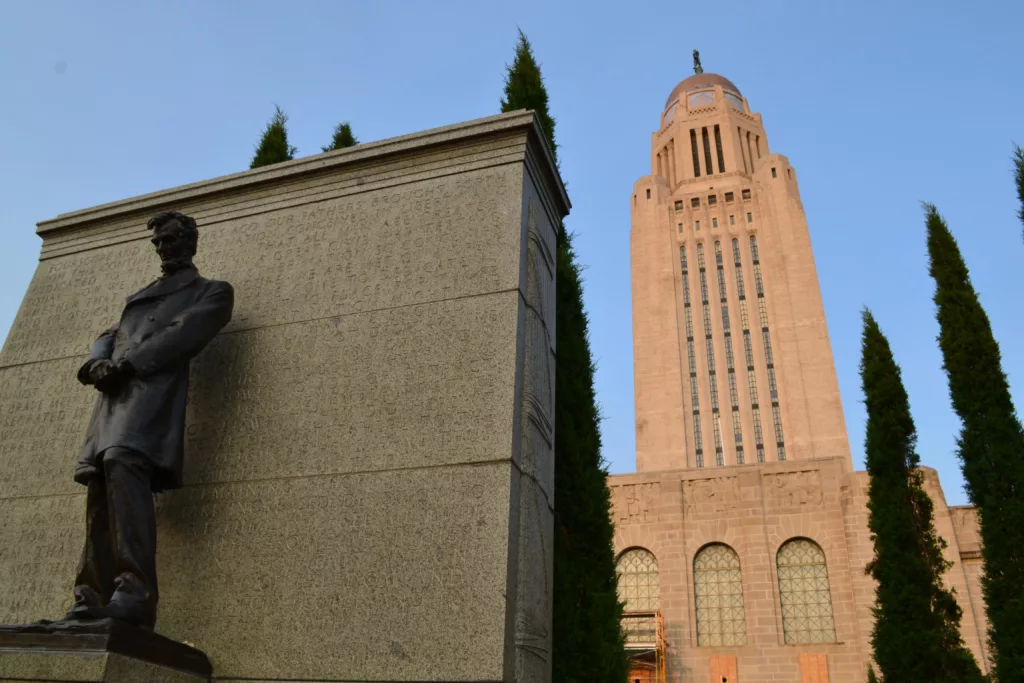

Taylor may be the “Home of the Taylor Juniper,” as the welcome signs now trumpet, but nowhere has it been granted a higher profile than Lincoln, 150 miles east, where the trees now bedeck – perhaps even complete – the capitol grounds. They guard the eastern doors. They stand vigil to the south. And on the west, they congregate around the Lincoln Monument, as if yearning for a better look at the president’s darkest hours.

“Call me some time,” says Capitol Administrator Bob Ripley, as if he’s long been waiting for this moment, as if finally someone asked. Because if these trees could talk, he says, they’d spin a tale of destiny.

When architect Bertram Goodhue submitted his design for the Nebraska Capitol Building in 1920, he included a number of soaring conifers to accentuate his 15-story limestone tower.

“They were monsters,” Ripley says. “If the trees in the drawing had been real, their scale would have been 50 or 60 feet in height, wider and taller than even the largest Italian Cypress I’ve ever seen.”

Goodhue died just two years into the build, but the Capitol Commission hired the state’s first landscape architect to implement his unrealized vision for the grounds. In less than two months, Ernst Herminghaus, a Lincoln native, created a new master plan, swiftly replacing Goodhue’s towering imports with the much hardier eastern redcedar. To ensure their upright growth, Herminghaus painstakingly sheared the branches.

“The problem was we didn’t have the skilled gardeners that we have today to continually prune those trees,” Ripley says.

After five years, the commission tore them out. Nearly half a century later, the commission tried Woodward Junipers, instead, a new tree variety from Oklahoma. They looked great in the beginning, then shed their needles and died. But “lo and behold,” Ripley says, racing ahead, right about that time the statewide arboretum began promoting an upright juniper – not unlike an Italian Cypress – discovered by a curious plantsman puttering through the Sandhills.

“It’s perfect. It’s absolutely perfect. If Herminghaus were alive today, he would sit down and shake his head and say, ‘I can’t believe this actually happened. The very tree that I was shearing 80 years ago now grows naturally.’ I’m sure he’d be amazed.”

***

Despite its exploding popularity, especially in tight urban spaces, the Taylor Juniper’s origin story is hardly complete. Wilke may have discovered it. Britton may have owned it. Cross may have grafted it, and the Nebraska Statewide Arboretum may have popularized it. But as one impassioned Loup County native asked in a letter to the editor years ago, “Is it nature’s aberration or His Divine Creation?”

For thousands of years, wildfires routinely swept through the Great Plains, relegating the eastern redcedar (actually a species of juniper) to riverbanks and rocky outcrops. Then white settlers arrived. They built homes and planted crops, and with so much now to protect, they viewed wildfire, in the words of novelist Bess Streeter Aldrich, as one more enemy to vanquish, “the fear of it forever branded in the minds of the settlers.”

No longer nipped in the bud, the eastern redcedar spread its scrappy limbs further into the open prairie, decade after decade, until it was swallowing pastures and evicting songbirds. Many ecologists now consider the so-called “Green Glacier” the biggest threat to rangeland conservation. Much of the prairie surrounding Taylor itself is no longer prairie at all.

At some point in the cedar’s long march, nature hiccuped. Exceptionally upright trees began sprouting from the hills. When Wilke first knocked on Britton’s door, in fact, the rancher knew of several others growing wild nearby. Today, ecotourists can drive the backroads between Taylor and Sargent, nine miles south, and spot dozens pricking the horizon, as if pruned by the great Herminghaus himself.

But scientists have yet to map the eastern redcedar genome; there’s no way to efficiently compare their DNA or pinpoint the gene in question. So the mystery remains: Is every Taylor-esque juniper somehow a novel mutation, or are they simply the offspring of some anonymous arboreal pioneer, what geneticists call “migration.” In Taylor itself, the rumors run wild. Some blame radiation from an ancient meteor strike, others nuclear drift from the Manhattan Project, others still an uncanny bolt of lightning.

Loren Sandoz, recently retired after 30 years with Loup County High School, shrugs them all away.

“I don’t buy it,” he says softly, manning a small picnic table in the square.

Years ago, his environmental science class experimented with these mysterious trees. Without a formal greenhouse, their attempts at grafting the uprights mostly failed. But they harvested seeds for propagation, too. Of the roughly 500 that sprouted, Loren culled 100 and planted them in one-gallon pots. Three years later, he says, most grew scrappy and loose, like any other eastern redcedar. Some were vaguely columnar. But four out of the 100 stood fully upright, imitating the mother tree.

With even this rough data in hand, says Donald Lee, a professor of plant breeding and genetics at UNL, “We can use the Occam’s Razor approach.”

The simplest answer, in other words, is probably the right one.

Consider it a random mutation, he says. Somewhere, somehow, the gene that normally controls the eastern redcedar’s shape failed to properly replicate. But unlike most trees, the eastern redcedar is sexed: to reproduce, pollen from the male needs to fertilize the female seed cone. As Loren’s students discovered, inheriting this rogue gene from the mother alone doesn’t ensure upright growth. But inheriting one from the father, too? Ask a redhead.

“I love a good genetics story,” Lee says.

But the ending hangs in the balance. Should their slender form prove somehow advantageous –

say by outcompeting their scrappier peers for sunlight – the columnar junipers could one day become the new normal in Loup County.

Or they could simply fade away by chance alone, so many aberrant genes passing like ships in the night.

But given how quickly the “Green Glacier” is swelling near Taylor, Lee says, the upright form will likely maintain itself as a minor percentage of the whole.

Loren hopes so. He still can’t explain how he became the Taylor Juniper guy, and he doesn’t try to. After an hour shepherding a reporter around his favorite mutant junipers, he rambles past the high school in his ‘98 Chevy, one plaid elbow hanging loose out the window. He points. He grins. “I’ve always admired this one,” he says. And that one came from the pasture. And that’s a certified Taylor, there, by the visitor center. And “that’s one we grafted,” he says.

An aluminum stepladder rattles in the bed as he eulogizes the one that got away.

“It grew from seed, and was so tight and beautiful at three years old, and I wish….”

He peers down the street and into the hills beyond.

“And I wish I’d kept it.”

4 Comments

I was born and raised in Holt County, NE.

Swell story. Beautifully told. Many thanks.

They are ruining the Sandhills.

Carson, “thank you” seems lacking of adequate emphasis to express how I feel regarding this article! This is a story that, in my opinion, needed to be organized and shared. You did a most respectful job of that. Like most things you think you know–there is a lot you don’t. My understanding of all aspects of this tree (from it’s natural mutation to what it is now) that began on my dad’s farm/ranch during his lifetime, now feels complete. I appreciate your efforts in creating this story.