KEARNEY – It’s late March and a million or so gray, red-capped sandhill cranes with gotta-dance attitudes have returned to their favorite spring break destination: Nebraska’s Central Platte Valley.

Daylight hours are spent eating in grasslands, wetlands and harvested cornfields. Cranes roost at night on river sandbars.

In recent days the narrow river section in the hourglass-shaped Central Flyway, an expansive migratory corridor stretching from south Texas to northern Canada and Alaska, began greeting endangered whooping cranes making shorter mid-migration stops.

“This is the only place in the world where this happens,” said Brice Krohn, president and CEO of the Crane Trust, which works to protect and maintain Platte River habitat for migrating cranes and other wildlife in central Nebraska. “This is North America’s Serengeti experience.”

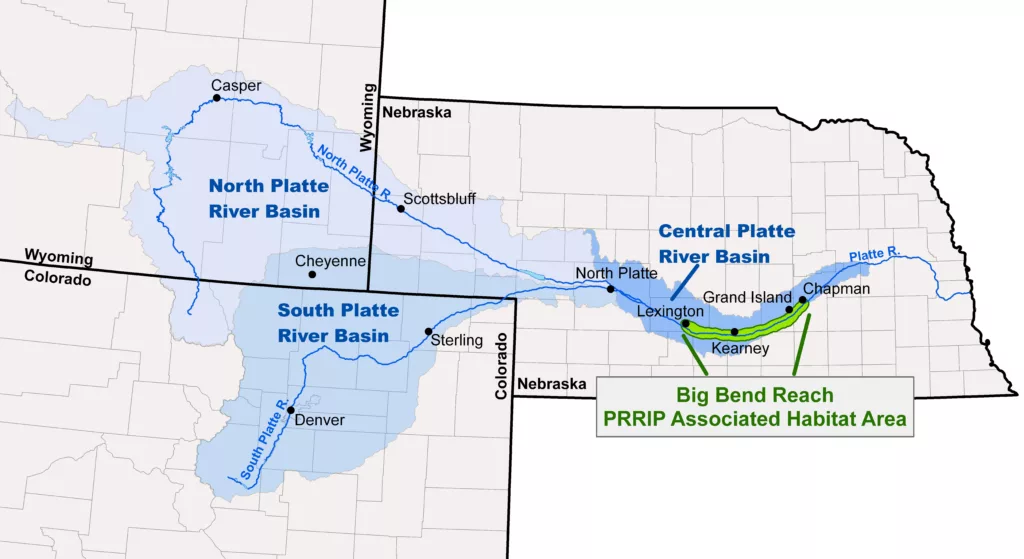

But wildlife habitat conservation is only one activity in the vast Platte River Basin, which originates with Rocky Mountain snow-fed rivers in Colorado and Wyoming that eventually meet in Nebraska to form the Platte River. The water also allows for irrigation, hydropower production, municipal water supplies, economic development and recreation.

Disputes – common whenever there is high demand for a limited natural resource – historically were settled with lawsuits, regulations and piecemeal projects. A court-approved settlement in one such suit led to the formation of the Crane Trust in 1978.

Two decades later, a unique alternative was proposed: Develop a partnership-driven, basinwide program involving the U.S. Department of Interior, the three basin states and stakeholders, with a focus on protecting the critical wildlife habitat in central Nebraska.

Now 26 years later, that novel approach has, by many accounts, proven to be a success, with an additional 10,000 acres of habitat restored and shortages in target water flows on the decline. It also helped stakeholders avoid burdensome regulations that could have led to less-effective conservation measures.

Human-driven changes to the river began when settlers built roads, towns and reservoirs. Farmers diverted river water to irrigate crops and later pumped hydrologically connected groundwater.

Over time, 70% of the basin’s original water has been removed or retimed by storing it in reservoirs, making the river an even smaller Central Flyway pinch point.

“We’re here to expand that pinch,” said Bill Taddicken, director of the Rowe Sanctuary, a nearly 3,000-acre site on the Platte River east of Kearney that is owned and managed by the National Audubon Society.

Developing what would become the Platte River Recovery Implementation Program was difficult, but necessary. The Endangered Species Act requires federal agencies to ensure that water projects don’t harm threatened or endangered species, or adversely modify their critical habitat.

By the time the idea for a basinwide recovery program gained momentum in the late 1990s, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had determined that threatened piping plovers and endangered whooping cranes, least terns (since delisted) and pallid sturgeon could be affected by water diversions and land use changes throughout the Platte Basin.

There were fewer than 20 whooping cranes left by the 1940s. Today, there are 838, including 543 in the wild flock that winters at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Texas and migrates on the Central Flyway.

Pursuing the recovery program allowed stakeholders that rely on the river to jointly address federal regulations concerning development and other activities that could negatively impact critical habitat.

Brian Barels, Nebraska Public Power District’s former relicensing director and water resources manager, said federal compliance costs likely would have triggered increases to electricity rates for all NPPD customers and irrigation system fees paid by farmers.

NPPD was one of two Nebraska public power districts working at the time to renew long-term federal licenses for hydropower plants. The process gave the district greater insight into the staggering costs that can accompany compliance with federal mandates.

As just one example, the federal agency that handles those licenses ordered NPPD to release stored irrigation water to build up river islands for tern and plover nesting. That was despite the fact that, according to Barels, NPPD biologists already knew the birds preferred nests on sandy beaches at Lake McConaughy and at sandpit lakes.

Plus, higher river flows would eventually wash away any islands created by the order.

“What kind of cost over 40 license years are you looking at to do that?” Barels said.

Central Nebraska Public Power and Irrigation District faced similar steep compliance costs tied to conservation efforts. Former General Manager Don Kraus said, “We were willing to do some things, but some things affecting the Central Platte habitat are in Colorado and Wyoming.”

Both districts offered to contribute to a basinwide plan. Central earmarked up to 100,000 acre-feet of water in Lake McConaughy as an environmental account U.S. Fish and Wildlife could tap when water was needed for Central Platte target flows. NPPD pledged its 2,650-acre Cottonwood Ranch habitat land along the river between Elm Creek and Overton.

First though, federal and state officials had to agree on whether to even proceed with developing a Platte Basin plan. After months of meetings, its future remained uncertain even hours before the vote to approve at a 1997 meeting in Lincoln.

“There were probably several ways for this to go south and we’re better off that it didn’t,” said Mike Jess, then director of the Nebraska Department of Natural Resources. “There wasn’t familiarity in the early days or an agreement on objectives. Unfamiliarity leads to distrust.”

Ultimately the U.S. interior secretary and governors of Nebraska, Colorado and Wyoming signed a cooperative agreement on July 1, 1997. Committees worked through 2006 on the program’s main elements: water, land habitat, and the science needed to identify projects and evaluate if they met goals.

“Once you got everybody there, the states, U.S. Fish and Wildlife, water users, conservation groups, there was some momentum going that this was going to work,” Kraus said.

Work started in the river channel, which had become choked with an invasive reed known as phragmites.

“It was just a phragmites jungle, so constant management of that has been important,” said Platte Program Executive Director Jason Farnsworth of Kearney. Wet years from 2011 to 2019 helped and millions of dollars were spent to spray and mechanically remove invasive vegetation.

The plan had two main objectives: protect and/or restore 10,000 acres of Central Platte habitat and reduce shortages to U.S. Fish and Wildlife target flows at Grand Island by 130,000 to 150,000 acre-feet annually.

By 2019, the land total was 13,810 acres. Another 184 will be added during the extension through 2032.

Target flow depletions have been reduced by around 110,000 acre-feet, Farnsworth said, and the extension calls for getting to 120,000 acre-feet as quickly as possible. Scientific studies then will determine if there’s a need to meet the original 130,000 acre-feet goal.

Researchers have confirmed that whooping cranes use acquired and improved habitat land, and that terns and plovers do prefer nests on sandpit beaches. Farnsworth said no sandbar nest has been seen in a decade, but river surveys continue each May through August.

“The program is vital today and to where we want to go in the future,” said the Crane Trust’s Krohn. “So far, everybody is coming to the table.”

Over the years, the program has directed millions of dollars to conservation efforts, with most of the cash contributions coming from the federal government, Colorado and Wyoming. Most of Nebraska’s contributions are in-kind habitat and water.

First increment (2007-2019) contributions of $317 million included $187 million in cash. Projections for the 2020-2032 extension total $156 million – $106 million in cash and $50 million of in-kind water.

Jess described the Platte River program as an enormous undertaking that couldn’t have been done piecemeal. “Plus, partnership no longer is a dirty word,” he said.

Without the partnership, states and stakeholders with interests in agriculture, energy, conservation, recreation, and economic development spurred by growing cities along the Platte River in Nebraska and Colorado’s Front Range would be competing for limited land and water resources.

“I see the program and what’s being accomplished with conservation and water use as the opposite of the descent into tribalism I see everywhere else,” Farnsworth said. “We are able to work collaboratively even when it’s difficult.”

3 Comments

I love reading Lori Potter. Very enlightening.

My grandma, Guadalupe Losa Delgado, owned property between the two channels of the Platte River, south of Gibbon, Nebr (Kilgore Island). It was awesome to visit when the cranes migrated each year.

A presentation of a wonderful story is freely shared while corporate Nebraska media is doing its best to control everyone that wants to learn about the cranes. No wonder that corporate is spinning down the hole to being of no interest.