KEARNEY – On an 11-acre plot in Kearney sit dozens of what look like shipping containers.

Inside the metal boxes are racks and racks of computers. Thousands of them, solving complicated math equations ‘round the clock.

Here on the outskirts of town, wedged between a solar field and a corn field, the thousands of computers mine for cryptocurrency.

Together, they use as much electricity as the entire city of Kearney, pop. 33,790, to do it.

This is one of the largest cryptocurrency data centers in Nebraska – a host site for the computers racing to verify crypto transactions and add to the digital currency.

It’s also likely the first of many such centers to set up shop in the state, as the still new and oft-volatile crypto industry carves out a home in rural America.

The instability of crypto has already hit the Kearney location – in September, Compute North, the company that opened the data center, declared bankruptcy. The Kearney property was sold to Generate Capital, one of the company’s lenders.

But even freefalling crypto prices, the infamous failure of crypto exchange FTX and the arrest of its co-founder Sam Bankman-Fried haven’t stopped the industry’s expansion in Nebraska.

Just last week, the Hall County Board of Commissioners approved the construction of a 14-megawatt crypto data center near Grand Island.

“We weren’t actively pursuing these, they came to us,” said Neal Niedfeldt, chief executive officer of Southern Public Power District, one of many Nebraska utility districts fielding crypto company calls in recent years.

A digital currency, crypto relies on a network of computers maintaining a blockchain – think of it like a digital ledger of transactions. The computers solve complicated math problems to verify transactions and add them to the ledger. In exchange, they receive digital “coins” – like bitcoin or ethereum – along the way.

The currency is largely unregulated and not tied to banks. It’s not backed by any government, like the U.S. dollar or the British pound. For crypto enthusiasts, the decentralized structure is part of the appeal.

“Basically, the business of crypto is converting electricity into computer computations,” said Gus Hurwitz, a law professor at the University of Nebraska College of Law.

Businesses like Compute North in Kearney function as a rental space for the computers making it all run. Crypto miners ship in their equipment, paying for space, maintenance, internet and – crucially – electricity.

With computers running virtually 24/7, and fans running to cool them, electricity is the main cost of doing business. The companies running these hubs need power. They’re looking for it cheap.

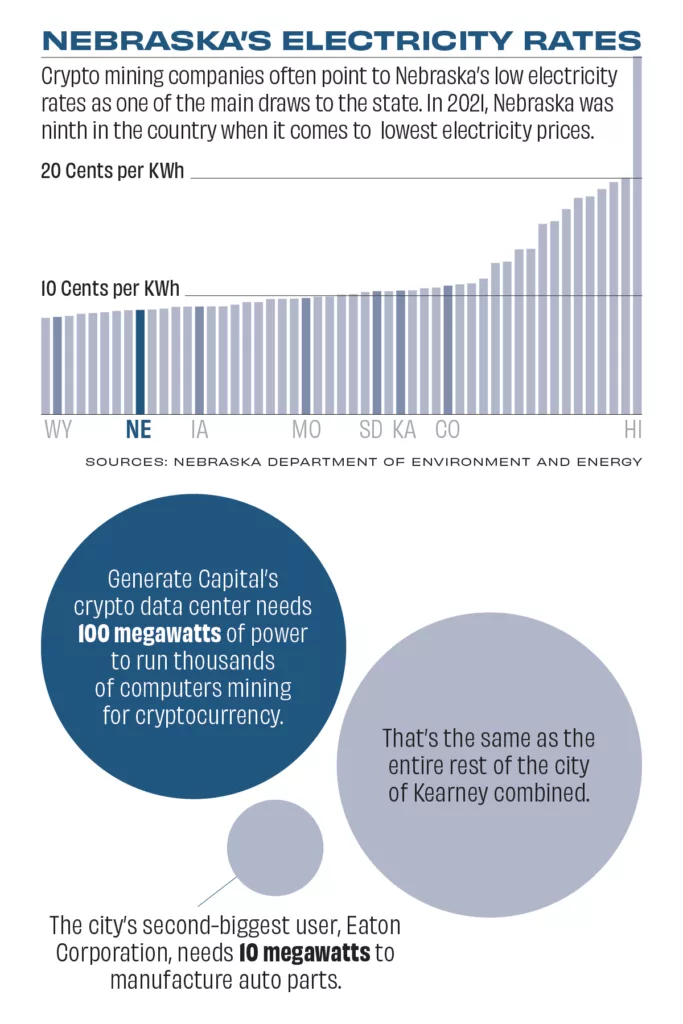

About five years ago, Compute North found it in Nebraska – the only state served entirely by publicly owned utilities mandated to deliver the cheapest electricity possible.

“They had heard our rates are low, and they’re stable,” said Nicole Sedlacek, economic development manager for NPPD. “That ultimately led them to put in a phone call to us.”

The company had a few other criteria: They liked the power district’s mix of carbon-free energy. They needed affordable land. They sought a place with the capacity to handle their massive electrical load, and a local government open to the idea of crypto coming to town.

Kearney had everything they were looking for.

The central Nebraska town had already been trying to develop its technology park. It was in the running for a Facebook data center, but lost the bid to Altoona, Iowa, about a decade ago.

A crypto data center promised jobs, but not in a way that would strain housing or take workers from employers already in town, said Stan Clouse, mayor for 20 years.

Clouse is also an NPPD account manager. He spent the first meeting with Compute North asking about their energy needs. What the mayor heard excited him, he said.

NPPD had enough electrical capacity to handle the data center, and wouldn’t need to generate more power specifically for Compute North. The data center would double the electrical capacity of Kearney’s power grid, making power more stable and keeping rates low. It would also mean an influx of cash.

“Increasing the load increases revenue, which goes into the Kearney general fund,” Clouse said. “That’s an excess of $1 million annually to Kearney. For a community our size, that’s pretty significant.”

But for some, the Kearney data center, and others soon to be running in Grand Island and York, aren’t to be celebrated. They’re a cause for concern.

“It’s not about job creation and opportunity for Nebraska,” said Scott Scholz, a spokesperson for the newly formed advocacy group Nebraskans for Social Good. “It’s about out-of-state companies leveraging our electrical system for their own profit.”

Save for Clouse, who abstained because of his utility role, the Kearney City Council voted unanimously in June 2019 to approve a development agreement with Compute North.

The company received 11 acres of free land, valued at $165,000 and paid for by the Economic Development Council of Buffalo County. The city gave the company a rebate on electricity, capped at $1.1 million. The company hit that cap in August.

Nebraska Public Power added mobile substations to help accommodate the increased load. The utility district is working on a new $12.5 million permanent substation that will exclusively transmit energy to the crypto-mining location.

In return, Compute North promised jobs, and delivered 11. It helped develop and add to the electrical capacity of Kearney’s tech park. By 2021, it grew to be a 100-megawatt customer.

By comparison: The entire city’s energy needs peak at 100 megawatts. The second largest user in Kearney is the manufacturing company Eaton, peaking at 10 megawatts, Clouse said.

The data center’s load is enormous and consistent – it doesn’t fluctuate through the day like the energy usage in a home or factory, said Pat Hanrahan, NPPD’s general manager of retail services. And it’s flexible. If NPPD needs more power from the grid to heat homes during a cold winter, for example, the data center can easily pause.

But the huge amount of electricity usage raises environmental concerns, Scholz said.

One year of global mining for cryptocurrency uses more electricity than the country of Argentina, according to an estimate in a White House report on crypto and climate change – as much as nearly 1% of the world’s annual electricity usage.

In New York, lawmakers recently passed a two-year ban on fossil fuel-powered crypto mining projects. In Montana, a coal-fired power plant was set to shut down, cheering environmentalists – until a crypto data center opened nearby.

In Nebraska, NPPD already had the energy capacity to power the Kearney data center, Hanrahan said. The public utility didn’t need to build new power generation to supply it.

Roughly 62% of NPPD’s energy generation is carbon-free, a number that remained steady before and after Compute North came to Kearney, said Grant Otten, NPPD spokesperson.

Still, a data center’s constant energy usage is likely to draw from all available energy sources, said Bruce Dvorak, a University of Nebraska-Lincoln civil engineering professor.

“It’s coming from a mix of more green sources, like wind, as well as not-so-green sources, like coal and natural gas,” Dvorak said.

Over the past five years, NPPD’s economic development arm has fielded calls from about 25 different crypto companies interested in Nebraska, Sedlacek said. The calls increased when China banned crypto in 2021.

Some towns, like Kearney, were open to the idea, Sedlacek said. Others have been more hesitant. They welcomed economic development.

“But we don’t want crypto,” they told her.

The crypto market is young, widely unfamiliar to the general public and wildly speculative and volatile. In November 2021, the price of bitcoin peaked at $68,764. Since then, it’s crashed by 75%, plunging to $16,625 in January.

In November, the crypto exchange company FTX filed for bankruptcy, shaking the already fraught industry. FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried was then arrested for multiple counts of fraud, sowing more distrust among crypto skeptics.

“We are definitely at a low point in the industry right now,” said Hurwitz, the law professor. “It’s possible we could get lower. Anyone entering into this market right now needs to be better capitalized, and capitalized in a less risky way than they likely were a year ago.”

Compute North, the company that opened Kearney’s data center, declared bankruptcy late last year, citing rising energy costs and profits that couldn’t keep pace as bitcoin value plummeted. The bankruptcy didn’t interrupt local operations. Today, the cluster of computers between a cornfield and a solar field continue verifying transactions and mining new cryptocurrency.

“Because they can move in so quickly, they can move out rather quickly, too,” said Sedlacek, the NPPD economic development manager. “We spent a lot of time as a utility really talking through that. How can we protect our ratepayers so we aren’t left stranded with assets and unpaid bills?”

She thought the calls would slow last year, when the digital currencies cratered. But the companies kept calling.

A handful of other projects are now in the works in Nebraska.

The York City Council decided in April to sell land to BginUSA, an Omaha company wanting to build an $8 million mining complex. In Minden, an expansion Compute North had planned is in the process of being transferred to New York-based Foundry Digital.

In November, a group of residents opposed to a proposed crypto data center near Doniphan crowded a Hall County Commissioners public hearing.

“This isn’t a farm facility going in,” resident Justin Gregg said during public comment, according to NTV News. “We grew up around a corn field. It’s all corn fields around us, and should stay that way.”

The interested company pulled its request for a conditional use permit before the commissioners voted.

This week, Hall County approved a conditional use permit for a different crypto project near Grand Island.

Questions loom around cryptocurrency’s future, including possible regulation and market prices. Last year, the Biden Administration released recommendations on future U.S. regulation.

Nebraska towns and utility districts now hopefully fully understand the risks they might face with crypto companies, Hurwitz said.

“Companies, municipalities, investors, bankers, lenders – anyone who was willing to fund things – is going to be doing so with much more awareness of the risks,” he said. “I would not be willing to take anything on credit.”

With crypto’s future uncertain, Sedlacek asks companies who call NPPD: What do you see this looking like in the future? And what happens if crypto goes away?

Many have told her they may eventually pivot their mass computer power to other industries, maybe banking, finance or health care.

“They really say that cryptocurrency is really their first step into this high-computing space,” Sedlacek said.

The Seacrest Greater Nebraska reporter covers issues across the state of Nebraska. It is named in honor of philanthropist Rhonda Seacrest and her late husband James, who proudly led several Nebraska newspapers through Western Publishing for 40 years.

3 Comments

Did anyone ask how much noise these facilities make?

Community leaders, neighbors, and reporters might want to ask that question.

See this article : https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/interactive/2022/cryptocurrency-mine-noise-homes-nc/

If you’re going to crypto and care about energy waste, use Proof of Stake (PoS) coins instead of Proof of Work (PoW) coins. My favorite is Cardano (ADA). Ethereum (ETH) is also PoS now and is the 2nd most popular coin in the world. Ethereum uses 40,000 times less electricity than Bitcoin (BTC) does.

People can learn more about Bitcoin and its enormous and growing reliance on electricity at the Change the Code, Not the Climate campaign website: https://cleanupbitcoin.com/