Mary Ann Beckman awaited the late-arriving guest from her open front porch on a quaint postcard of a block that might have faded into Omaha oblivion had it not been for people like her husband, Mel.

Saving Bemis Park was among Mel Beckman’s many noble aims. He rehabbed old houses, pushed the city to save single-family homes from being chopped into apartments and started one of Omaha’s first neighborhood associations.

This was but one example of how Mel, a former Catholic priest turned anti-war and criminal justice advocate, and Mary Ann, a pediatric nurse by trade and a de facto social worker, try to live their values.

In ways big and small, public and quiet, grass-roots and quixotic, the couple have spent their lives in service to others.

“What one person could do. What one couple could do,” said Jeanie Mezger, a friend who recently took over the criminal justice newsletter that Mel founded. “They have touched a lot of lives and have made things better and made it easier for people on the inside to feel they are connected to something on the outside.”

Mezger and others recently gathered at the old Holy Family Catholic Church — a place where the couple worshiped, raised three children, and found others dedicated to activism and service — to celebrate the Beckmans’ lifetime of “peace and justice work,” as a friend put it.

The event also represented a passing of the torch.

At 85 and 86, Mary Ann and Mel still support the same causes. But they are winding down. Mel handed over the Nebraska Criminal Justice Review to Mezger. Though Mary Ann drove some voters to the polls on Election Day, she has long retired from Catholic Charities, where she worked most of her adult life.

They agreed to sit for an interview with this somewhat late visitor (who, for the record, came bearing coffee) with the stipulation they do it together, just as they’ve approached every challenge since meeting over 50 years ago.

***

Sitting at their well-used dining room table, over which hangs a map of the world with family pictures and prayer cards tucked in its frame, the Beckmans took stock of what they had set out to do amid the messiness and heartbreak of life.

Of the three children they adopted years ago, only a son lives — and he is in prison with a parole date they may not live to see. Holy Family, their longtime Catholic parish, no longer exists as a church — the Omaha Archdiocese closed it during the COVID-19 pandemic. The world seems no closer to peace than when they met in the 1960s.

And yet, this soft-spoken pair did not seem dissuaded or embittered.

“Just keep the work going,” Mary Ann suggests. Mel nods.

They were Nebraska farm kids who found meaning and purpose in the state’s largest city. Mary Ann grew up in Poole, a rural community between Ravenna and Kearney. Mel is from Raeville, born the 11th of 12 children.

She wanted to be a nurse. He wanted to be a priest. Their paths crossed when Mary Ann landed a job with Catholic Social Services, which later became Catholic Charities. Mel, ordained a priest during Vatican II, the early 1960s effort to modernize and bring the Catholic church closer to the people it served, was working as associate pastor at St. Mary’s in South Omaha.

Mary Ann wanted to help young people, principally young mothers in poverty, some of them unwed and in desperate straits.

A priest showed up to help. Mel.

“We were trying to get things going that needed to be done,” Mary Ann explained.

They were quick and easy collaborators at a time of social upheaval and change. Like many young men and women who entered Catholic religious life in the ’60s, Mel decided he could not remain a priest.

But quitting the priesthood while remaining in good standing in a church he loved proved hard. He had to seek formal dispensation from his vows before he could marry. The process took over a year, during which Mel voiced his dissent with church policy on the celibate priesthood in an open letter published in The True Voice (now The Catholic Voice).

Mel placed an old-but-pristine newsprint copy of that letter on the dining room table. Its direct but polite language foretold a future of dissenting against powerful institutions while inviting engagement on seemingly intractable subjects.

“I am no longer convinced that the policy of mandatory celibacy is serving the best interests of the Church in our times,” Mel wrote in 1970.

He said he wasn’t “angry with the Church,” and offered to personally provide readers with more information.

He used the same approach on issues from neighborhood improvement to world peace.

The church, for its part, did not make the dispensation process easy. After taking a year to grant his request, the church told Mel that if he wanted to marry at a Catholic church in Omaha he could use a tiny chapel inside St. Cecilia Cathedral. The cathedral itself was off limits. Mel and Mary Ann married at a Catholic church in Kearney instead, packing the place with their large families and friends.

The couple settled into the wood frame house on a leafy stretch of Lafayette Avenue — the house that’s still home. On the corner stands historic Augustana Lutheran Church, where a young pastor’s attempt to bridge racial divides was famously captured in the 1966 documentary, “A Time for Burning.” The Beckmans found a home in a different progressive congregation.

In those days, Holy Family bustled as “the hippie parish” as retired Creighton University professor and Beckman family friend Linda Ohri dubbed it. Holy Family centered itself around service to the poor. It started the homeless shelters that evolved into Siena Francis House and a sack lunch program that continues to this day.

The Beckmans joined and instantly felt at home. Mary Ann sang and sometimes played piano at Mass.

Mary Ann worked for Catholic Charities. Mel bought, fixed up, and rented or sold houses in the neighborhood. He organized various peace groups. He wrote prolifically — letters to the editor, op-eds, brochures, newsletters. His name appears hundreds of times in the Omaha World-Herald archives.

A sampling: He questioned nuclear deterrence policies, called on the Nixon administration to end the Vietnam War, criticized the establishment of junior ROTC programs in public junior high schools and backed Sen. Ernie Chambers’ push to end Nebraska’s death penalty by electric chair. And that was just the ’70s.

He made national news, too. In 2001, CBS News featured Mel in a story about former FBI Agent Robert Hanssen who was caught spying for the former Soviet Union. Hanssen also participated in an old FBI domestic spying operation, collecting intelligence on ordinary Americans like Mel Beckman, who had come to the bureau’s attention for opposing the junior ROTC program.

“That created some excitement on the block,” Mel recalled.

He also appeared in a story about being a “house husband.” Mary Ann worked the day job and Mel — while juggling his home repair business and advocacy — raised their three children: Kathy, Christine and David.

Each had been adopted through Catholic Charities at different times. Each brought joy, warmth, but also challenge into the home on Lafayette Avenue.

Kathy went through two prior placements before the Beckmans brought her home at about age 5 a year after they had married. Kathy later married, had two children, but died at age 38 in a head-on collision that was ruled a suicide. Christine, adopted next, grew up and had a daughter but died of breast cancer in 2018 at age 44.

Then there was David. Ohri, the family friend, remembered David being a loving and engaging kid. But he struggled in school, Mel and Mary Ann said, and became an impressionable young adult.

David built up a rap sheet and by age 20 went to prison for the first of two substantial sentences. In 1996, he was convicted of sexual assault and sentenced to 10 to 30 years. He was released in 2010 but returned to prison in 2020 on felony drug and weapons possession convictions. David’s first chance at parole is in 2034. His parents, if still alive, will be 95 and 96 then.

David has an 8-year-old son.

***

The Beckmans’ interest in the criminal justice system long predates David’s entry into prison. But his experience spurred them to start the Nebraska Criminal Justice Review newsletter and a support group, Family and Friends of the Incarcerated.

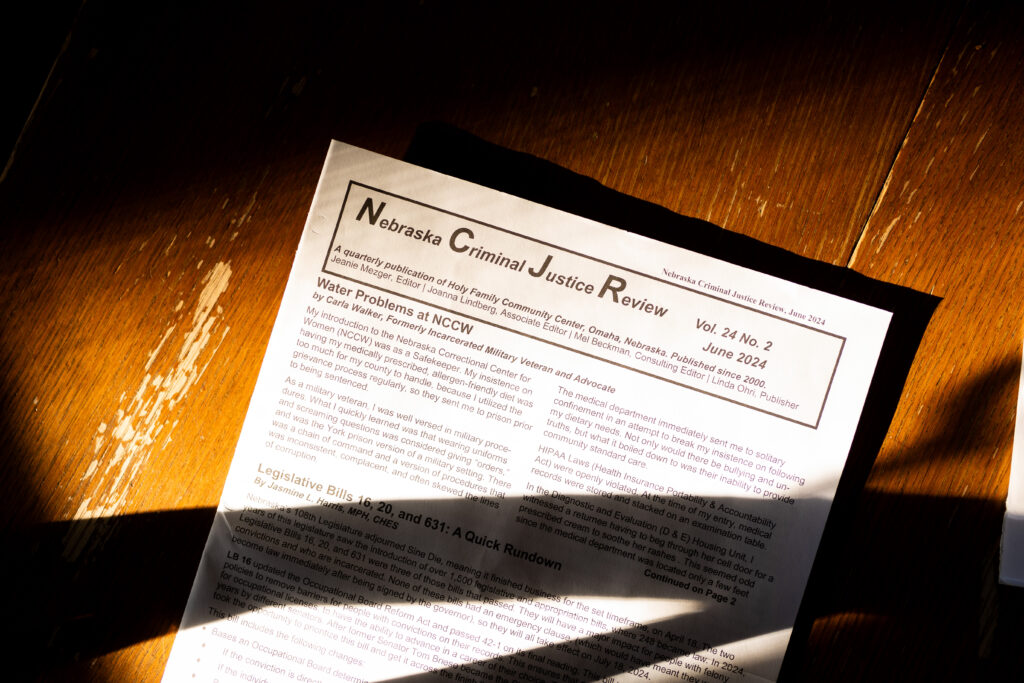

The review is published quarterly and its archives are housed online by Creighton University. The printed 12-page document goes to some 1,400 subscribers, about 400 of whom are imprisoned in Nebraska.

Its most recent edition featured numerous articles on felon voting rights, solitary confinement and a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision allowing communities to impose criminal penalties on homeless people. The newsletter included letters from Nebraska’s incarcerated population. There’s a glossary of abbreviations of Nebraska correctional facilities and a schedule for Family and Friends of the Incarcerated and a nonprofit group, Nebraskans Unafraid, to support those convicted of sex offenses.

Mel envisioned including commentary from leaders of Nebraska’s criminal justice system as a way to bring all parties to the table to discuss system improvements.

Dayne Urbanovsky, spokeswoman for the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, said the department receives the newsletter, reads it and has contributed to articles. She credits the newsletter and Mel for providing a way for incarcerated people to maintain bonds that are important for successful reentry.

Douglas County Public Defender Tom Riley called the newsletter “a great resource for information” and said the Family and Friends of Inmates support group gives voice to the quiet suffering of families. He attends the monthly sessions and thinks local judges should show up as well.

“It’s important to know how sentences impact families,” he said.

Despite their soft-spoken nature, the Beckmans have displayed persistence, honesty and passion, Riley said.

“They really do care about the folks imprisoned. They care about their families,” he said.

Mezger, the current newsletter editor, said the Beckmans believe that small actions can have big results.

Chiefly? Beckman helped lead the effort to ban life sentences for crimes committed by Nebraskans aged 17 and younger, following a 2012 U.S. Supreme Court decision.

“I would call Mel ‘quiet,’” Mezger said. “He’s never angry. But he’s not satisfied with the way things are and he’s trying to change that. He’s doing it without taking his anger out on people who disagree with him. He wants to educate, he wants to speak up and be heard.”

Mary Ann is “not as quiet” as Mel, said Mezger, but also doesn’t show anger.

“And there’s plenty to be angry about,” Mezger said, citing a prison system that can feel opaque, confusing, dangerous and at times unnecessarily punitive.

For their part, the Beckmans say the work is not done but they gave their causes a good try. And they have done it together.

As they walked the stranger to the door, Mary Ann turned to her husband and gently said, “You’re a good one.”

“It takes one to know one,” Mel responded.

“Well,” Mary Ann said, patting his arm. “I know one.”

21 Comments

What a wonderful article about one amazing couple! I’m privileged to know you!

Thank you for your service Mr and Mrs Beckman

Thanks, Erin, for telling the story of this beautiful couple. I appreciated hearing of their passion, perseverance, and dedication to ‘lifting people up!’

It was indeed balm for my soul today. There are so many folks doing the good work of building kind and caring communities, pursuing peace, justice, and humbly walking with their God and others. We need to hear their stories.

Blessings to them and their works of compassion.

With appreciation.

Amen!

Wonderful article! It sure shows us that age doesn’t matter to still be a change for good.

Thank you for another great piece about ordinary people doing interesting and important work

Great story! Thanks for publishing!

Thanks for shining a light on these shining lights in our community! The rich and powerful dominate our daily news – it is refreshing to learn about the quiet warriors for justice among us!

Love the article. I’ve known and loved the Beckmans for 50 years and they have been inspirations to many, many people. This only touches on some of their work, and we all feel blessed to know them.

I’ve known this couple for years. They’re among the finest people I know and true examples of true Christian love and compassion. I’m honored to know them. Thank you Erin Grace for this wonderful article!

Mary Ann and Mel have been Heroes of mine for over 50 years. They have shown the way Jesus intended all of us to live every day. They make it look easy. I know that they have made countless sacrifices in order to make it look easy. Thank you, Erin, for this wonderful tribute.

These people are my Uncle and Aunt. You have truly captured the essence of who they are. My memories of Mel go back before he was a priest and he certainly lived his life in the way you describe him.

Thank you for this wonderful article.

Beautifully written by Erin and thanks for publishing this. They were truly a prophetic couple! so kind and and gentle spirited.

Always enjoy Erin’s stories. Great read.

Erin, I love the way you write! Great story about great people.

Erin really captured the Beckmans personalities and lives. They have been unsung heroes for many decades. I had the honor to work with Mel on a few issues and was struck by his humble demeanor while fighting to make life better for others. What a wonderful couple. Thank you for your work in bringing unsung heroes to light, Erin!

I enjoyed this article so much Erin. Thank you for showcasing the good work being done and the need that goes on.

Wonderful! Amazing people working on the front lines with dedication. We need more Beckman’s.

I grew up in Poole as well! It is always good to read an article about someone from the community! And, add my commendation for the work the two have done over the years. Merry Christmas!

Inspirational. What the heck am I doing with my life?

Erin Grace is one of my all time favorite reporters and storytellers! Lovely account of two lives well-lived. I better get to work in order to do even half of what Mary Ann and Mel have done throughout their lives! A special thanks to them for making our community a better place and living the values of their belief in God.