GIBBON – Cody Wagner sat in a mustard-colored canvas blind along the Platte River on a cold March 2021 night and focused a night vision scope on a half-dozen sandhill cranes among the tens of thousands settling onto overnight roosts.

A symphony of trills, bugles, hoots and squeaks filled the air as cranes circled, lowered their feet, curved their extended wings and floated hang-glider style down to crowded river sandbars.

Some, including the small group Wagner was observing, flew up to try again for more comfortable spots to spend the night.

He watched as one crane struck the lowest of five strands of wire on a 69-kilovolt power line spanning the Platte west of Rowe Sanctuary’s Iain Nicolson Audubon Center southwest of Gibbon. As it fell, the other cranes in the group flew away.

“The crane was still upright. It started walking back to the roost and was calling to all the other cranes there. It wasn’t capable of flying,” said Wager, the Sanctuary’s conservation program manager. “It was really hard to watch. Seeing that kind of thing makes you want to do anything you can to keep the birds from dying.”

Wagner and two other central Nebraska crane experts spent the 2021 crane season collecting data about how cranes behave near the power line, and searching for something that will lower the number of collisions that maim and kill cranes.

Now they think they have an answer: Shining powerful UV light on the power lines, making them more visible, appears to save the lives and damaged wings of sandhill cranes as well as whooping cranes, an endangered species.

A new avian avoidance collision system, installed at the Rowe Sanctuary, decreased collisions by nearly 90%, say the experts, who have captured the promising results in soon-to-be-published research.

“It shows that this kind of technology can be effective for use on other structures that also are potential hazards to cranes,” Wagner said.

Wagner knows this work is important because he knows the fate for a crane unable to fly from the river the next morning to feed in area grasslands, wet meadows and harvested cornfields. The birds must be healthy enough to continue a spring migration of 2,000-plus miles from southern Great Plains wintering areas, primarily in Texas and New Mexico, to breeding grounds in northern Canada, Alaska and Siberia.

Most of the nearly 1 million large gray, red-headed sandhill cranes congregating in the Central Platte Valley use the Kearney-to-Grand Island river segment – many of them flying right by the power line. Their late winter-early spring stop to rest and refuel is one of the world’s great migration events.

A few weeks later, endangered whooping cranes flying roughly the same migration route stop for a few days at some of the same south-central Nebraska habitats. Researcher Dave Baasch, threatened and endangered species specialist at the Crane Trust near Alda, said U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service staff sightings indicate whooping cranes spend a quarter of that time on the Platte River.

Sandhill cranes are big, with wingspans up to 7 feet. And fast – they can fly 35 miles per hour. They are also tough, able to stand for hours in freezing water and survive blizzards.

But the cranes aren’t always agile enough to evade collisions with power lines they see at the last minute.

To try to help, the Sanctuary installed a collision avoidance system that includes battery-powered light boxes and solar panels in February 2021.

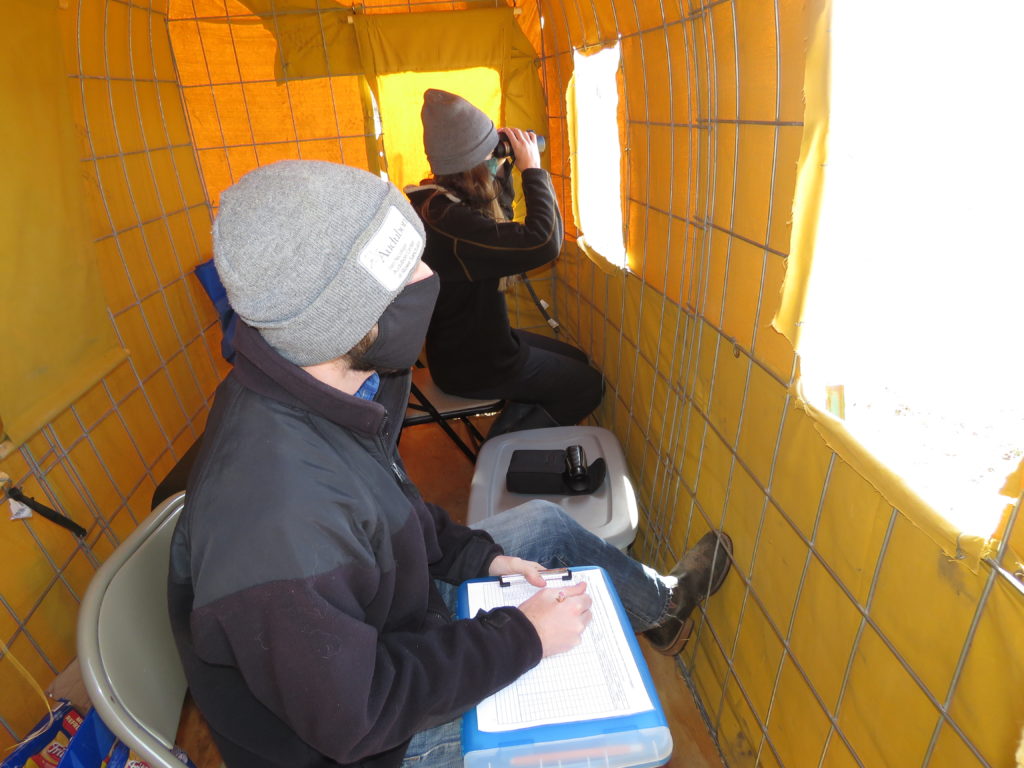

It was this avoidance system that Wagner, two other experts, University of Nebraska at Kearney students and a group of volunteers studied. Wagner and Rowe colleague Amanda Hegg spent many 2021 crane season nights in the south riverbank blind, watching cranes interact with the power lines and observing how UV light might be able to help. They watched crane behaviors near the power line and collected data to determine if shining UV light down such lines can reduce crane collisions, especially at night.

The research paper by Wagner, Hegg and Baasch has been approved for publication by the Journal of Avian Conservation and Ecology.

The findings are stark.

When the lights were on: One crane collided with a power line.

When they were off: 63 did.

“When the lights were on, cranes avoided the power lines sooner,” Baasch said. “Not only were the collisions reduced, the reactions were quicker.”

The team determined the likelihood of power line collisions decreased by 88% when UV lights were on. Hegg said the light is mostly invisible to human eyes.

While in the blinds, one person used binoculars – night vision after dark – to watch cranes’ behaviors near power lines and give verbal descriptions. “Climbing” up and over lines. “Flaring,” when a line is seen and dangerous aversion actions take cranes up, over or through lines. “Reverse,” when cranes saw the lines from a distance and turned around.

The second observer took notes on a form for later database downloading.

“There were a few days when the weather made it difficult to record things, but we never didn’t want to go out and do it,” Wagner said, including times when water entered the blinds and high winds made it unsafe to stay for a full shift.

The light boxes remained on after crane season to help eagles, hawks, geese and other birds avoid the power lines.

It’s unknown if UV lights are as effective in other seasons and for other species.

“We only know what they do this time of the year,” Hegg said. “Not all birds may see the same.”

Baasch hopes the Rowe lights last at least 10 years.

Man-made structures are far from the only hazard for sandhill cranes. Other dangers: Legal late-fall-into-winter crane hunting in other Central Flyway states, predators, disease, and habitat changes that include growing water demands for agriculture, municipalities, businesses and other uses.

“There also are the perils of migration in general,” Hegg said, primarily body mass loss. Weight gain is the main reason sandhill cranes make a mid-migration stop at the narrowest point in the hourglass-shaped Central Flyway.

While many migration season hazards for sandhill cranes can’t be eliminated, central Nebraska conservationists now know that simply shining a light on power lines can save lives.