Dustin Shephard was 23 when a Sarpy County judge sentenced him to 10 years in prison for attempted second-degree sexual assault and abuse of a vulnerable adult.

When he finished serving his time, Shephard thought he’d head home. Instead, he was sent to a state-run psychiatric hospital in Norfolk. Shephard was no longer an inmate, he was a “patient.”

He remained confined for about four more years. Then he was shipped back to Norfolk – not for a sex offense, but because he lapsed into drug use. Now 38, Shephard is back at the Norfolk hospital for a third time following a prison sentence for assaulting hospital staff.

He’s one of dozens of Nebraskans involuntarily committed to the Norfolk Regional Center after serving sentences for crimes. At least one had failed to register as a sex offender. Others were convicted of rape.

Some were originally committed over a decade ago, and often have no sense of when they will get out.

Talk to Shephard, and he will tell you he’d rather be behind bars.

In prison, there’s a release date. In the state hospital, patients remain in custody until authorities determine they can be released.

The state leaders who enacted this system reasoned that it was the best way to protect Nebraskans – that it could catch the most dangerous offenders and get them needed treatment before they could strike again.

But some Nebraska public defenders and patients think the system warehouses men instead of rehabilitating them. Experts question whether the costly system effectively combats sexual violence.

“Do I think that the concept is, in itself, flawed? Not necessarily,” said Douglas County Public Defender Tom Riley. “But the way it’s being practiced turns it into, pretty much, almost a life sentence for something that the Legislature said is not a life sentence.”

A bipartisan answer to heinous crimes

The political will to pass Nebraska’s Sex Offender Commitment Act in 2006 was strong and bipartisan. The goal: protect children.

“We have come a long way in dealing with sexual predators, yet more can and should be done,” Gov. Dave Heineman, a Republican, said at the start of that legislative session.

Former Sen. Pat Bourne, an Omaha Democrat, chaired the Judiciary Committee and introduced Legislative Bill 1199.

The bill, requested by Heineman, was comprehensive – residency restriction rules, new penalties, enhanced penalties, more offenses that required registration, lifetime community supervision and expanded civil commitment to treatment for some offenders leaving prison.

It passed 47 to 0, without a single “no” vote.

The law requires the Department of Correctional Services to evaluate certain people and determine if they are a “dangerous sex offender” before they’re released from prison. Among other things, that requires finding they have a psychiatric or personality disorder that makes them likely to reoffend.

A county attorney can then pursue civil commitment of dangerous sex offenders through a three-member mental health board, which ultimately decides if treatment – inpatient or outpatient – is necessary. The board is required to choose the available, appropriate treatment that “imposes the least possible restraint” on a person’s liberty.

“I think there are a number of checks in place to make sure everybody’s getting evaluated that needs to be, and that we’re doing what we need to do,” said Chris Seifert, deputy county attorney in the Lancaster County Attorney’s Office. (Correction: This article incorrectly identified the official in the Lancaster County Attorney’s Office.)

About 20 states and the federal government allow the civil commitment of sex offenders who’ve finished their sentences. Transcripts suggest that Nebraska’s act was modeled after Kansas’ law, which the U.S. Supreme Court upheld. The state Supreme Court upheld the Nebraska law’s constitutionality in 2009.

An American Psychiatric Association task force condemned the laws in 1999, writing in a report that they “represent a serious assault on the integrity of psychiatry” and that the profession must “vigorously oppose” them.

These laws, the task force found, are in truth designed to extend punishment and protect society.

‘We’re doing a great job’

Shephard and the other Norfolk patients stay mostly inside a three-story brick building, behind an imposing chain-link fence topped with razor wire. It’s just a few miles from downtown Norfolk, on the site of an old State Hospital for the Insane.

Since 2006, 225 men have been committed to the Norfolk hospital under the sex offender law.

The Flatwater Free Press spoke to six of those men. Their time confined in state hospitals post-sentence ranged from a few years to eight – a couple were later recommitted to Norfolk from outpatient treatment. Essentially, the Norfolk facility taught them to follow program rules, a few said.

“There’s people right now sitting at Norfolk who have been there 10, 15 years,” said former patient George Shepard. “Some of those people there right now, they’re not there because they need to be there, they’re there because they don’t know how to play the game.”

Don Whitmire, hospital administrator at the Norfolk facility, said treatment there aligns with national standards. And, he noted, there’s a reason – and a professional opinion – that the patients need to be there.

“We’ve been tasked with providing this service,” Whitmire told the Flatwater Free Press during a tour of the grounds. “I think we’re doing a great job.”

Treatment is individualized and includes about 30 hours of “therapeutic activity” a week, according to a DHHS document. The program focuses on “reducing deviant sexual attractions, arousals and fantasies, and developing and maintaining appropriate sexual attractions.”

Dustin Shephard, the current patient who has been through the program before, said he starts some of his days – after breakfast and free time – with recreational therapy. The room has weights, treadmills and video games.

Then his unit meets to share goals for their day. Staff gives them a paper on a “therapeutic topic” that they discuss, he said.

After lunch most people play cards, read or nap for a few hours, he said, unless they’re in a group. Shephard goes to his one-hour chemical dependency group twice a week.

Some days there’s occupational therapy – “arts and crafts-type stuff.” Other days, he has his sex offender group, where patients complete the program’s core assignments. Most people have individual therapy scheduled every one or two weeks, he said.

Typically, his only opportunity to spend time outdoors, in a fenced-in courtyard, is 4-5 p.m. After that is dinner time, then the unit reconvenes to talk about whether they met their goals. Two televisions come on at 6 p.m., with programming decided via a group vote.

It’s lights-out for Shephard at 10 p.m. on weekdays and 11 p.m. on weekends.

He works six hours a week now, for minimum wage, cleaning bathrooms.

“I know I’m not progressing at the rate that I could, or even if I do progress at the rate that I can, that it won’t be acknowledged,” Shephard said.

The sex offender program accounted for about 18% of the $134.5 million DHHS spent on mental health services through its division of behavioral health in fiscal year 2023, according to DHHS data.

From Norfolk, patients can progress to Lincoln, then eventually discharge. Patients placed in outpatient must follow their treatment plan or risk going back to the hospital.

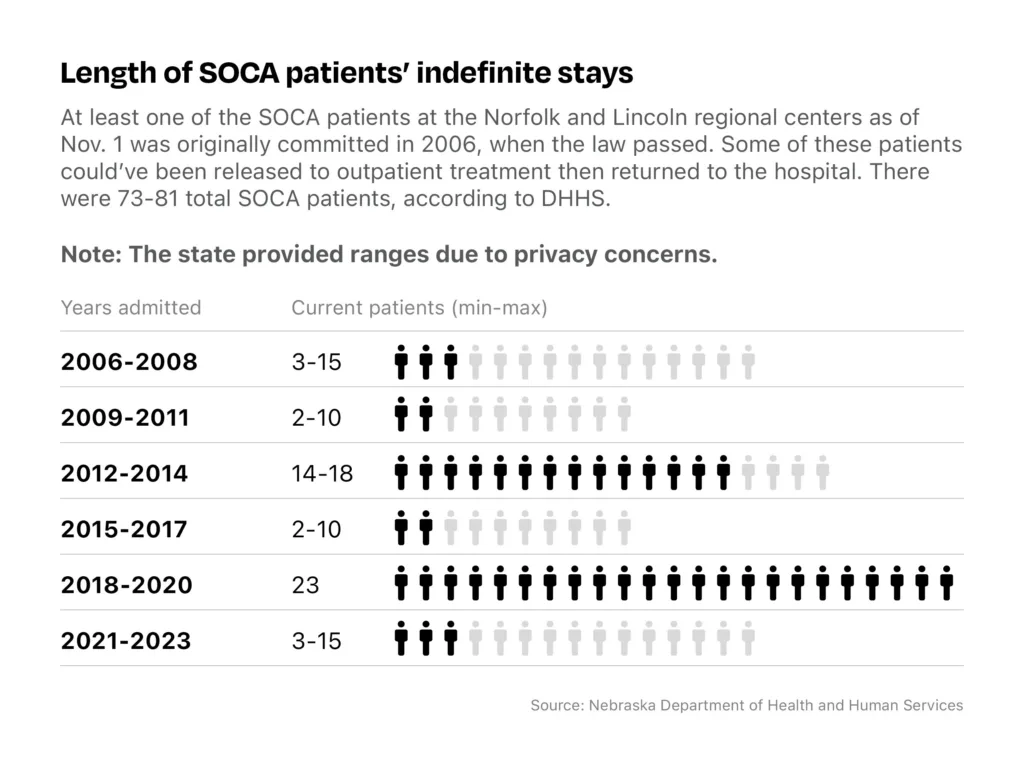

As of Nov. 1, there were between 73 and 81 patients committed under the Sex Offender Commitment Act at the regional centers, according to DHHS. The department, citing privacy concerns, often provided ranges instead of specific numbers.

At least 13 – and as many as 37 – of these patients were originally committed to the program in 2013 or earlier.

The length of someone’s stay depends on their “motivation to change,” a program manual reads. But progress can feel arbitrary and prolonged to patients and their advocates, who say small rule violations can extend confinement.

Grand Island attorney Jon Hendricks, who has handled cases as a prosecutor and defense attorney, said he wished there was more outside oversight of patients’ progress.

“Seems to me if you’re taking somebody’s liberty like this, then having some kind of check system in place might be critical,” he said.

A DHHS spokesperson said current personnel couldn’t recall lawmakers ever conducting any oversight hearings but said the sex offender program was evaluated by an outside consulting group in 2018.

The office of the state ombudsman overseeing institutions receives complaints from patients, families and staff regarding DHHS facilities.

But DHHS has severely restricted the office’s access in the wake of a 2023 Attorney General’s opinion. According to last year’s report, the ombudsman could only see areas that are open to the public for its annual inspection. DHHS submitted its own facilities report to the Legislature.

“Due to the limitations in the … ability to review, analyze and verify complaints, systemic issues are undetermined,” the ombudsman’s report reads.

Jeanie Mezger, board member for Nebraskans Unafraid, a nonprofit that advocates for changes to sex offender registration policy, called what happens in civil commitment “largely invisible.”

“Everybody has their eye on Nebraska prisons, but who watches this DHHS program?” she said.

No typical story

George Shepard, the former patient, got through the sex offender program quickly.

He was convicted of first-degree sexual assault in 1978 and served prison time, and was later convicted of first-degree sexual assault of a minor and visual depiction of sexually explicit conduct involving a child. He served 25 more years in prison.

Shepard was civilly committed in 2015 and discharged in 2018, he said. He was in outpatient treatment for two years, and he’s been out from under a mental health board’s supervision since then, though he said he stays in touch with his outpatient therapist.

Dustin Shephard, the current patient, has had a more turbulent experience.

In 2009, he pleaded guilty to attempted second-degree sexual assault and abuse of a vulnerable adult.

The victim, Shephard’s then girlfriend, was taken to the hospital in critical condition, required a blood transfusion and underwent surgery after he sexually assaulted her, according to a protection order request filed by the woman’s guardian. The guardian referred to the woman as “mentally handicapped.”

Shephard participated in the sex offender treatment program while in prison. He found the program helpful and he was just short of completing it when he hit his release date, he said.

Instead of being released, Shephard was held at the county jail for about six months. An independent evaluation recommended outpatient treatment, according to Sarpy County Public Defender Tom Strigenz. But the mental health board ultimately committed him to Norfolk.

Shephard felt like he wasn’t afforded due process and said he’s felt “helpless, perpetually, since then.”

He went through treatment in Norfolk and Lincoln, then was released to outpatient treatment in late 2017. About a year and a half later, he started using methamphetamine and acting erratically.

Outpatient providers are required to report problematic behavior. That happened in Shephard’s case. His provider noted his drug use made him a higher risk to reoffend, according to Strigenz. He hadn’t committed a new sex offense, but he was taken back to Norfolk’s sex offender treatment program.

According to DHHS, 19 people have, like Shephard, been recommitted for violating an outpatient agreement.

Immediately, Shephard says, he lost much of the life he had started to build outside. And he was back in a place that felt worse to him than prison.

There are hundreds of people in prison. Here, he’s mostly stuck in his unit with the same 20 guys. There are rules in both places, but in Norfolk his behaviors were dissected using the worst of interpretations, he said.

In prison, he said, he could do four hours of treatment and still have 12 hours to work out, go to the library, play basketball or hang out outside. Here, the boredom and time spent indoors stretched out in front of him.

He attempted suicide, he said. He harmed Norfolk staff.

“I gave up, and I started attacking staff just so I could go back to prison – just so I could go outside, just so I could listen to music and watch TV,” he said.

In 2020 he pleaded guilty to three felony charges of third-degree assault of a DHHS employee and one misdemeanor charge of third-degree sexual assault and served three more years in prison.

Shephard was sent back to the hospital in Norfolk, a third time, after that sentence ended last fall. Strigenz, who said he has represented clients in at least 30 of these cases since 2006, is pursuing another independent evaluation.

“Dustin is not the most dangerous sex offender that I’ve represented,” he said. Shephard’s choice to fight the system rather than go along with it has added to his trouble, Strigenz said.

‘We just warehouse them’

Part of the sex offender treatment program’s vision: “no more victims.” DHHS said it’s aware of three former patients committed under the Sex Offender Commitment Act who have been convicted of an additional sexual assault charge.

The department pointed to a U.S. Department of Justice report and a 2015 international analysis that both concluded some treatment programs show promise in reducing recidivism and more research is needed.

Focusing on recidivism fails to address the larger issue of sexual violent crimes, most of which are not reported, said Eric Janus, director of the Sex Offense Litigation and Policy Resource Center at Mitchell Hamline School of Law. And those offenses that are reported are most often committed by first-time offenders, he said.

An analysis published in Brooklyn Law Review in 2013 found that laws like Nebraska’s “have had no discernible impact on the incidence of sex crimes.”

“The civil commitment laws … have a small effect on recidivism. And recidivism itself is a small part of the problem of sexual violence,” said Janus.

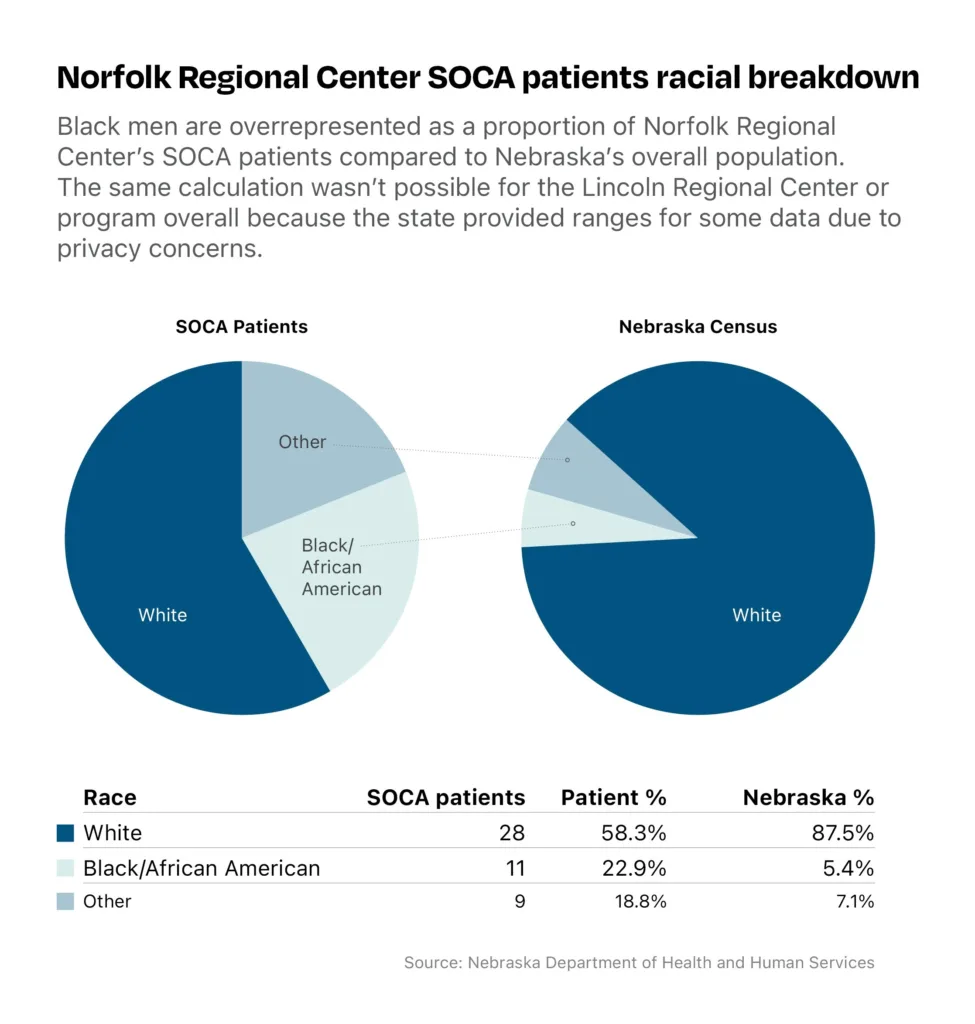

The programs can also disproportionately confine Black men, according to a 2020 report from the Williams Institute at UCLA Law. In Nebraska, it found the detention rate of Black men was more than three times higher than the detention rate of non-Hispanic white men.

In 2012, researchers compared Nebraska’s committed offenders to other states’ and found that Nebraska “commits moderate- to low-risk sex offenders to inpatient settings at such a high rate” that it “merits consideration of whether this practice represents the most fiscally responsible use of the state’s limited correctional and mental health dollars.”

Lancaster County Public Defender Kristi Egger said that still rings true.

“We’re over-punishing, in my opinion,” she said. “It’s supposed to be rehabilitation, but we are incarcerating people, basically – over-incarcerating, just like we do in sending so many people to prison.”

Public defenders point to a lack of resources at multiple points.

Like in Shephard’s case, people can’t always complete treatment while in prison, which would reduce the likelihood of being civilly committed.

There’s also a shortage of qualified providers who can conduct independent evaluations – assessments that can influence the mental health board’s determination. And there’s a lack of outpatient providers and housing once offenders complete their sentences.

“If we did it the way it should be, and it was really fair and fairly administered, and we had enough people like caseworkers and treatment providers, it could work and be beneficial,” Riley said. “But, given the situation that we find ourselves in … we just warehouse them.”

‘The only legal remedy’

There’s no indication that state lawmakers are planning to examine this system.

Judiciary Committee Chair Sen. Justin Wayne of Omaha said he wasn’t aware of any issues with the Sex Offender Commitment Act or any legislators who are working on it.

In a recent interview, Bourne said LB 1199 felt “novel and balanced” at the time. He understood criticisms of civil commitment, but noted this law deals with people who’ve “arguably committed the most atrocious, heinous crimes that any of us can even imagine.”

U.S. Rep. Mike Flood, who prioritized the bill as a state senator from Norfolk, said he’s visited NRC several times and talked to the people inside.

“Reality is that, under the law, once they’re out of prison, this is the only legal remedy,” he said. “We have to protect the public by providing treatment in a therapeutic setting.”

Still, Bourne said he was “stunned” that the law hadn’t been revisited.

He’s surprised, partly, because his sex offender bill that became law also called for the creation of a task force to improve the state’s management of sex offenders.

“When you say they’ve never adjusted the bill since, that kind of flies in the face of the intent of that committee,” he said.

Shephard and other patients said they understand the rationale for the program but feel it’s not serving its purpose.

“I understand what they (lawmakers) did and why they did what they did,” Shephard said. Somebody else decided “to bastardize those statutes and use them as a bludgeon against anybody who has a sex offense on their record.”

The Flatwater Free Press is Nebraska’s first independent, nonprofit newsroom focused on investigations and feature stories that matter.

6 Comments

We will never achieve perfect justice on this Earth as long as our court system is made up of human beings. (And AI is no answer) We must prioritize the protection of children and all vulnerable people, even if, at times, we jeopardize “fairness” for offenders. We must continue to strive for humane treatment and rehabilitation of incarcerated persons.

i’m not surprised by the lack of transparency in the Nebraska civil commitment program. The 20 states that have such programs have little transparency. I ran into similar issues when writing reports on Texas and Minnesota.

U.S. Rep. Mike Flood inadvertantly told us the real intent when he said, “Reality is that, under the law, once they’re out of prison, this is the only legal remedy.”

The REAL intent is extending time behind bars. Are they not offering treatment during incarceration? If so, is Flood the dud implying treatment while incarcerated is worthless?

The fact that NE’s civil commitment statute passed by LB 1199 in 2006, which also allowed municipalities to create their own residency restriction laws. (This is another useless law in need of repeal.) These politicians created this bill largely in response to Persons Forced to Register fleeing the onerous residency restriction laws in Iowa that had passed the year before. This was not about “protection”; this was about deterring people these politicians hate from living in Nebraska.

This law passed years ago, so we can now stop pretending this is about “protecting the public.”

I am a retired sex offender treatment from the State. Of Iowa. Although retired I keep my interest in this area. I wonder if I could help out in the State of Nebraska !

The whole mental health system in Nebraska has been dismantled. For example, in 2016, the county board in Lincoln closed the Lincoln Lancaster Community Mental Health Center, that provided excellent follow up for persons who left the Regional center. Just one example of how we fail to meet the needs of persons who would benefit from services for mental health issues.

My son is currently “warehoused” at NRC, after serving his sentence for one count of possession of child pornography. (Meaning he had ONE picture.) He also had a previous charge when he was 15 years old. Because he is autistic, he’s considered high risk to reoffend.

He’s been told, by some of the staff there, that, because of the way the program “works,” he will likely never be released.

Where you going with this?