Mujtaba Karimi crowded with hundreds of others outside a half-open gate to Hamid Karzai International Airport one night last August. Afghan or maybe American soldiers fired their rifles in the air and launched tear gas, trying to disperse the crowd.

Karimi didn’t run. He couldn’t.

The 27-year-old was an up-and-comer in the Afghan government. He lived in a nice apartment. He drove a Toyota Land Cruiser, wore good clothes. But by August the government had fallen to the Taliban, President Ashraf Ghani – Karimi’s boss – had fled and the United States and its allies were evacuating. Everybody wanted out. Karimi needed out. As a government official, he was no longer safe.

He waved his blue official Islamic Republic of Afghanistan passport in front of a beefy American soldier at the gate. He yelled “Diplomat!” – the only English word he knew that came close to describing his status.

The soldier reached out and grabbed Karimi, pulled him through the crowd. Suddenly he was on the other side of the gate. He was on his way to something entirely new.

“It was a small thing,” Karimi said. “But it changed my life.”

Today, the 27-year-old lives in Omaha. In some ways, it’s not bad. He has a decent apartment. He takes English classes at the University of Nebraska at Omaha – he’s much more comfortable with English than that perilous day in August.

In other ways, it’s hard. In Afghanistan he could leave work at 4 p.m. Today he works second shift and is up past midnight studying. He once worked for his nation’s president. Now he works for Walmart, pushing forklifts loaded with boxes into the store.

He wants to become a citizen. He wants to attend the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. He knows he will need to take more English classes and haul more boxes before he steps behind those ivy walls.

The fall of Kabul spurred a mass exodus. Roughly 75,000 Afghans have come to the United States since. As of last week, state officials say 1,214 have resettled in Nebraska.

Some are educated professionals like Karimi, who fled because they were Taliban targets. Others fled because they could see no future under the Taliban.

“Everybody is just trying to get out of Afghanistan because of the restrictions and poverty,” said Sayed Omar Sadat, 27, who fled Afghanistan because his wife worked in the U.S. Embassy in Kabul. “The passport department is crazy nowadays.”

The sudden Afghan influx caused chaos in Nebraska. So many arrived in such a short time that it overwhelmed resettlement agencies. These agencies had faced years where they received almost no refugees or funding because of Trump administration policies that severely limited both. In the last nine months, following the Biden administration’s abrupt pullout from Afghanistan, they have been forced to hurry into action.

“Because the airlift happened over a quick, two-week, period … there was very little time of actually very little structure around how those resettlement efforts would happen,” said Matt Martin, assistant vice president for refugee and immigrant programs at Lutheran Family Services of Nebraska. “In a normal world, that’s a very structured process.”

Kubra Haidari, former Afghan refugee and now case manager for Omaha’s Refugee Empowerment Center, said chaos reigned from August until February.

“Every day we were working, from like early morning…till 12 o’clock at night,” she said.

For many, an arrival in Nebraska was a bureaucratic accident. Sadat and his wife wanted to go to Virginia, but it had reached its Afghan limit. An immigration agent told him they were going to Omaha.

“It was the first time I had ever heard of Omaha,” he said.

He Googled it. That’ll work, he thought.

Many Afghans arrived with their documentation in disarray – or none at all. Most came in under a humanitarian parole status that allows them to stay only two years. They must change to another status or face deportation.

More than half had to go into temporary housing, some for a significant period, Martin said.

Some hiccups have resulted from well-meaning people trying to help. A Grand Island meatpacker brought six families to central Nebraska so the adult men could work in the plant. A lack of planning meant the families ended up living in a hotel.

“A situation where a significant number of people are just dropped into a community without forethought and planning is really a recipe for, if not disaster, then at least some chaos and confusion,” Martin said.

At the Empowerment Center, intake works like this: The refugees are met at the airport and taken to their first residence, often an Airbnb. On the second or third day they are brought to the office. Staff explain basics, like calling 911 in an emergency.

Next comes cultural orientation.

Ahsan Arian, 29, a new arrival, said some of his fellow refugees are puzzled by things like a smartphone or Google Maps. “They don’t know about voice mail,” he said. “They don’t know about texting.”

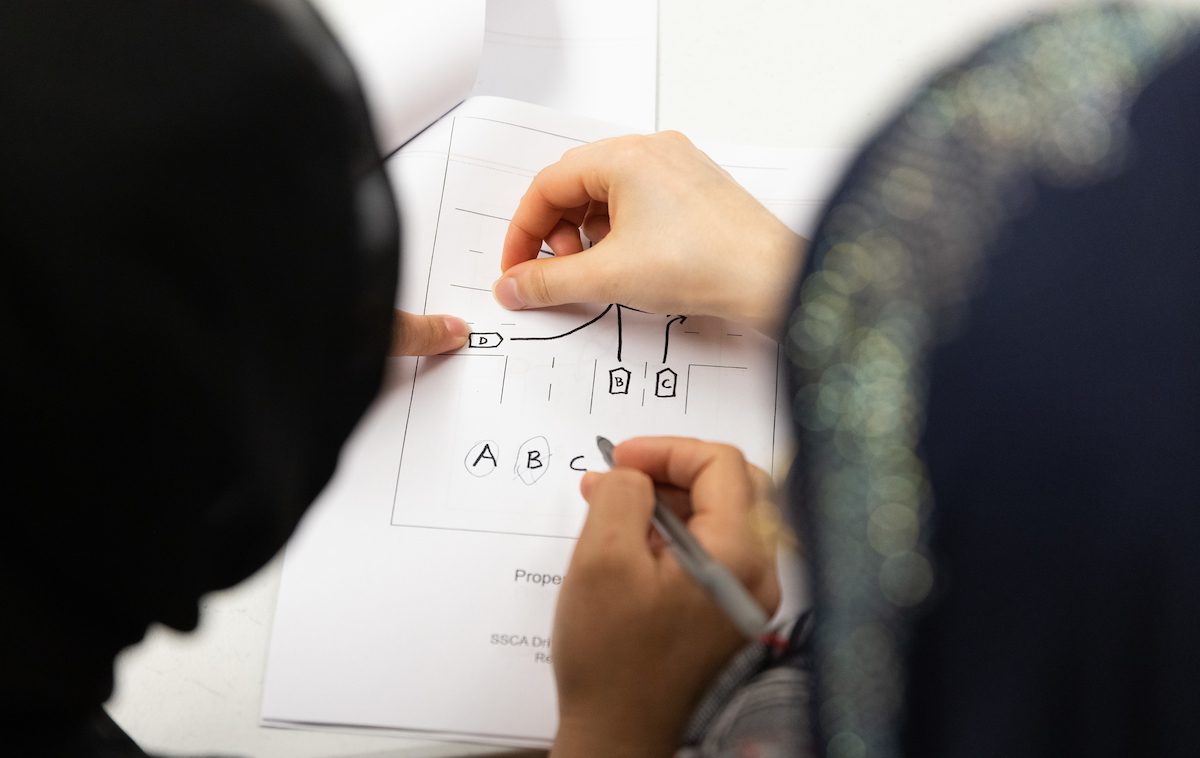

Driver’s license training is critical. Many Afghans have experience driving, but motoring the streets of Omaha is a very different experience than in Kabul.

One client drove for twenty years in Afghanistan. Here, he was befuddled by all the stoplights and signals.

Many women don’t know how to drive at all. And driving is important for women who stay home with children while their husband works. Their lives in Nebraska open up if they can learn to drive. It helps them show their husbands they are equal, Haidari said.

The housing chaos made life difficult for parents to get their kids into schools. Many showed up without records of required shots. Children can’t go to school without a vaccine card. And they can’t attend without a permanent address – Omaha Public Schools doesn’t want them to enroll in one school, then move to another a week or month later.

New Afghan arrivals struggled with these things while continuing to grapple with the heartbreaking ways they left their homes.

Arian was a journalist for French broadcaster RFI in Afghanistan. The Taliban murdered some of his colleagues. His bosses told him he should leave. When he did, he had to leave behind his parents, his wife, his 14-month-old child.

He prays it’s temporary, hopes he will soon reunite with his family and build a new Nebraska life.

“I can’t live without them,” he said in his northwest Omaha apartment, where the living room consists of a donated chair, a stool and a busted Sony TV.

In Afghanistan, being a journalist is dangerous, but respected. In Omaha he works the assembly line for Airlite Plastics.

“I was something more in Afghanistan, but here I am something other,” he said.

Even though Arian is educated and knows English, here the pronunciation and the speed are different. He’s starting an ESL course and hopes to be fluent soon.

As the Afghan arrivals continue to adapt, Lutheran Family Services is preparing for the next wave of refugees: Ukrainians. President Biden has said he will accept 100,000. But they should arrive in stages, not one giant airlift. Already the agency has greeted Ukrainian walk-ins.

“Right now we are challenged on that front because there is no Ukrainian refugee program, at all. And so the services that we can provide are very minimal,” Martin said. “But we are trying to do what we can to provide at least some basic needs, emergency support…We are preparing to support more as necessary.”

1 Comment

Nice story Andrew!