In January 2017, Patrick O’Donnell entered the Nebraska State Capitol’s cavernous legislative chamber, air heavy with the echo of history’s fierce debates and whispered negotiations.

He stood in a familiar spot, the one on the dais reserved for the clerk of the Legislature, the position he’d held for nearly four decades. He felt the familiar anticipation, peering down at the state’s 49 elected senators exchanging greetings around their desks.

But to O’Donnell, it already felt different — felt as if something undeniable was changing. “A turning point,” he’d later come to consider it.

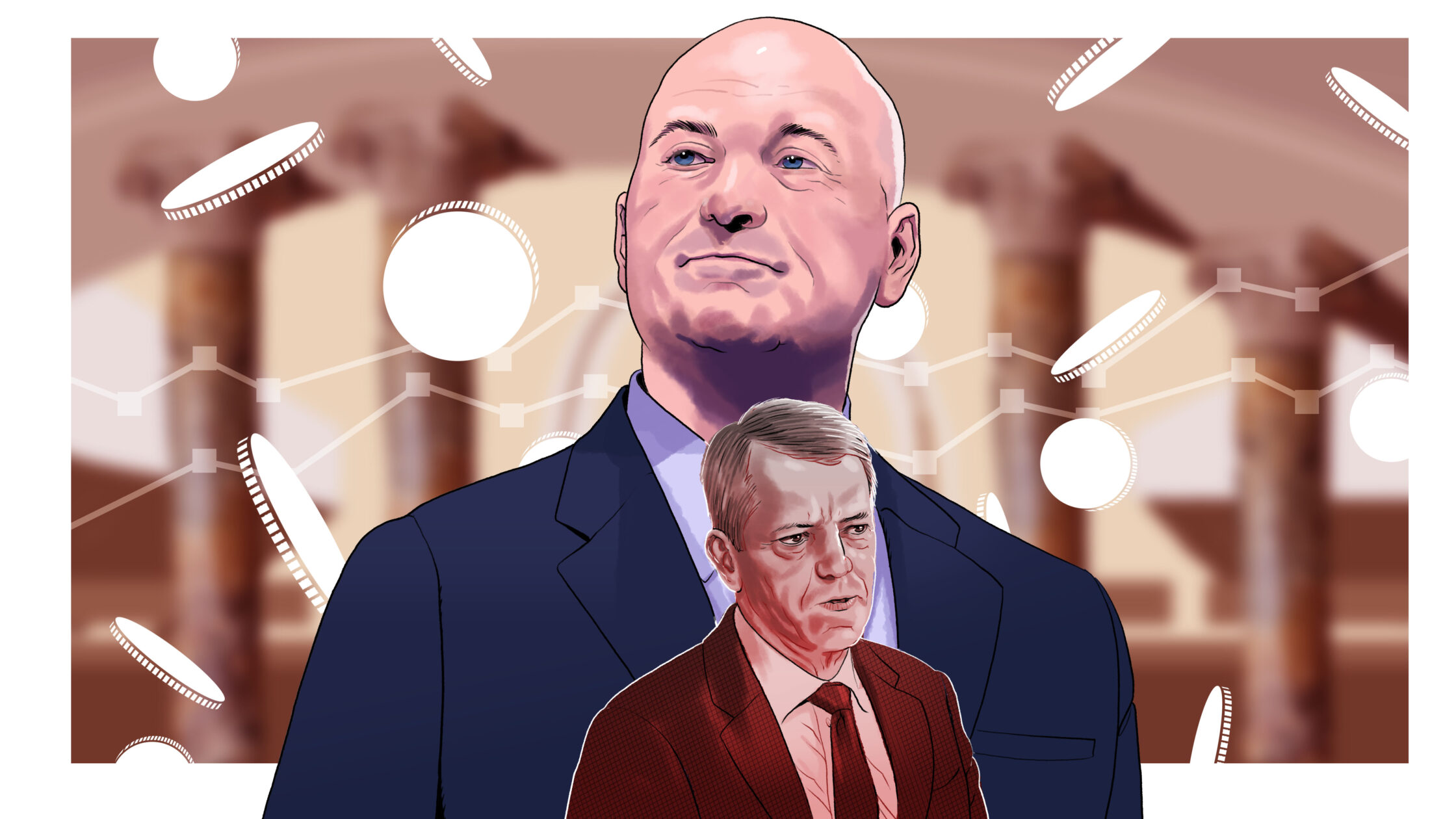

This January 2017 morning followed the first election where Gov. Pete Ricketts used his deep financial resources to help shape the Legislature determining the fate of his own policy agenda. Nine senators, all but one new, had received campaign contributions from Ricketts.

O’Donnell, who retired in 2022 after holding the clerk’s position for 45 years, noted that several in the new class arrived lacking the curiosity that generally bubbled up in eager freshmen legislators every two years.

“I think they came in with a community of purpose and weren’t particularly interested in listening to other sides or alternative perspectives,” he said of many senators aligned with Ricketts.

During the decade when Ricketts ran for and served as governor, he and his family spent at least $624,000 on candidates for the Legislature, according to a Flatwater Free Press analysis of Nebraska Accountability and Disclosure Commission filings. That’s in addition to the more than $1.6 million they gave to the Nebraska Republican Party and the more than $560,000 they spent on political action committees advocating for or against candidates for office, including the Legislature.

The influence of the Ricketts family’s money is impossible to unbraid from other factors — including national politics and term limits — that longtime observers said were already transforming the nonpartisan tradition of Nebraska’s Legislature.

But the governor’s spending did contribute to a rise in partisanship, those observers say. Senators began to collaborate less. They showed more deference to the governor’s office.

It fueled a culture shift that extends to this day.

“I think we saw the executive branch starting to set the legislative agenda for the legislative branch,” said Perre Neilan, who’s been lobbying the Legislature for 24 years. “And, unfortunately, we saw — for a number of years — the polarization of the members of the Legislature, much like we see in Congress.”

****

The 2016 elections proved a staggering debut of Gov. Ricketts’ willingness to get involved in heated political races and causes.

The year prior, his first in office, a bipartisan majority of lawmakers voted to increase the state’s gas tax. When Ricketts vetoed the bill, senators voted to override him and pass it anyway.

A week later, over Ricketts’ opposition, they voted to abolish Nebraska’s death penalty. Then they allowed recipients of the federal Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program — referred to as “Dreamers” — to get driver’s licenses. Ricketts vetoed both, and, again, senators voted to override him.

The next year, lawmakers OK’d professional licenses for immigrants authorized to work. Again, a veto. Again, an override.

The governor and his parents poured at least $425,000 into a petition effort — $300,000 from the governor himself — that led to Nebraska reinstating the death penalty.

In the same election, the governor supported challengers who ousted three Republican senators who had voted counter to his agenda.

He spent at least $126,500 supporting legislative candidates during his first election cycle in the governor’s office, more than quadruple what he’d spent in the two elections prior.

And he was strikingly successful. Nine of his preferred candidates won. In races between two Republicans, his candidates won four of five.

Ricketts’ team often interviews candidates to help him understand their “political philosophy,” said Jessica Flanagain, his longtime political adviser. Ricketts has declined interview requests for this series.

The governor has never made a secret of what guides his support.

At the state Republican convention ahead of the 2016 election, Ricketts advocated for electing “platform Republicans” and called out specific GOP senators who didn’t align with the party, according to the Lincoln Journal Star.

It prompted a bipartisan group of 13 senators to issue a statement asserting the Legislature’s nonpartisan history.

“Governor Ricketts believes political party trumps principle,” they wrote. “Our nonpartisan, unicameral legislature has lasted for eighty years, and, barring the will of the people for a new legislative experiment, we will not surrender our nonpartisan and constitutional duties.”

****

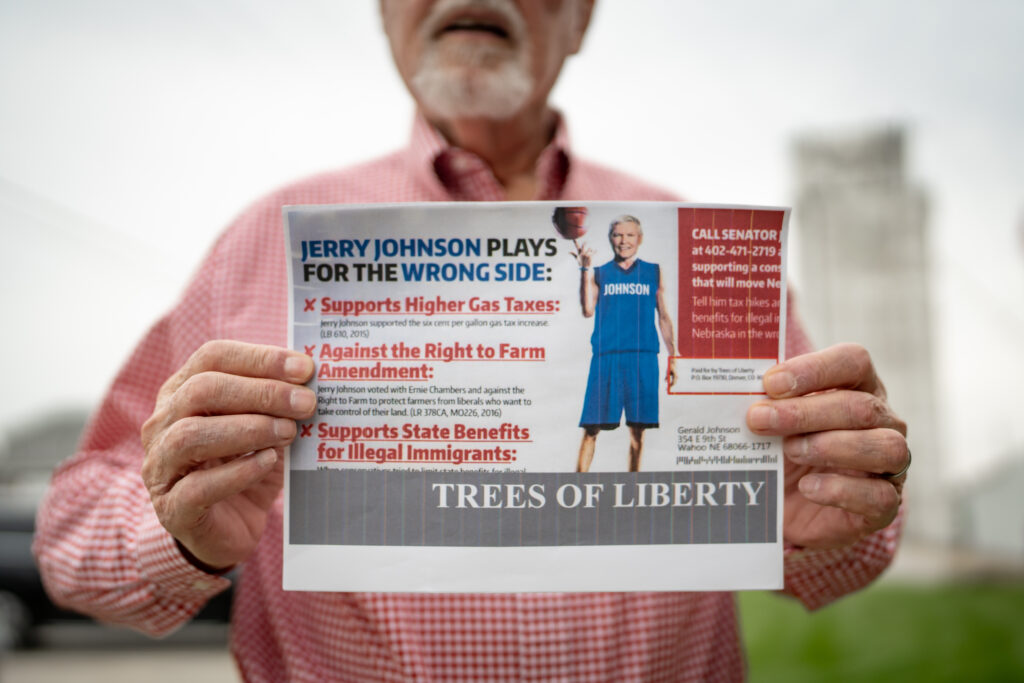

Voters ousted Jerry Johnson, Al Davis and Les Seiler during Ricketts’ 2016 push to defeat fellow Republicans who bucked him on votes. Johnson and Seiler had chaired influential committees in the Legislature.

“They were all three Republicans. They were good senators. They were diligent. They were leaders in the body,” said William Mueller, who has been lobbying the Legislature since 1984. “The governor supported and funded the Republican opposition to the Republican incumbent. That is, in my experience, unheard of.”

It’s not as if the governor was fully bankrolling their opponents in those races.

Ricketts donated $5,000 to Sen. Tom Brewer’s successful run against Davis, about 8% of the total amount Brewer raised that cycle.

He gave $13,000 to support Sen. Bruce Bostelman, who beat Johnson – nearly a third of Bostelman’s contributions.

And he gave $10,000 to Sen. Steve Halloran, who beat Seiler. That was about 29% of his total.

Money alone doesn’t win a legislative race, said former Gov. Dave Heineman, a Republican. Door knocking and alignment with voters on important issues are key, too.

Likewise, Davis, who later ran for lieutenant governor as a Democrat, said Ricketts was only one factor in his defeat. He mentioned his stance on renewable energy as a tension point, and remembers local radio host Jim Lambley railing against him on his KSDZ morning show as the “Ernie Chambers of the West.”

But the Ricketts’ money and influence did matter, he and Johnson say.

They suspect Ricketts was linked to attacks paid for by Americans for Prosperity and Trees of Liberty, conservative groups that hammered away at them as they tried to win a second term. Ricketts originally brought Americans for Prosperity, a national organization tied to the Koch brothers, to Nebraska. Trees of Liberty is also affiliated with the Kochs, according to national reporting. Those groups don’t have to disclose all their donors.

Flanagain, who worked as a special adviser in Ricketts’ administration around this time, said in a statement that Ricketts stopped contributing to Americans for Prosperity in 2013.

“There were multiple occasions where (Americans for Prosperity) supported his focus to lower taxes over his eight years as Governor, but he did not seek to influence their organizational decisions, including campaign spending,” Flanagain wrote.

Brewer beat Davis by about 5 percentage points — fewer than 800 votes. Bostelman easily bested Johnson. Halloran crushed Seiler by 20.

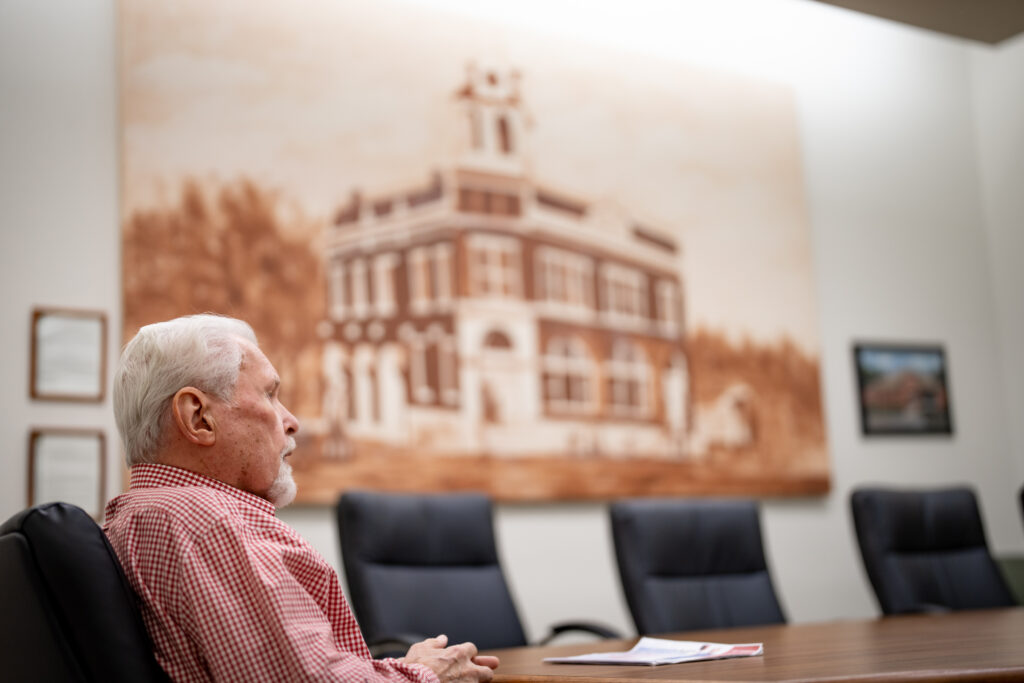

Johnson, now the mayor in Wahoo, drew a distinction between serving with Ricketts in office and serving with his predecessor, Heineman. Heineman might call his office and ask him to explain his thought process and why they differed, then move on.

“Ricketts would call, and that was not the case,” Johnson said. “He was … ‘You better do this.’”

The three senators’ departure sent a message to other senators, some observers said.

“He targeted them, and he got them, and that has a really chilling effect going forward,” said John Lindsay, a former state senator who’s been lobbying since 1997. “When you talk about that era … that’s a watershed moment, because it was clear that the governor was willing to spend money.”

In a few cases, splitting from Ricketts has appeared to have longer term consequences.

Take former Sen. John McCollister, who eventually grew nationally prominent for opposing Donald Trump while refusing to leave the Republican party.

McCollister served on the board of the Metropolitan Utilities District for 30 years before he was a senator. He worked as executive director of the Platte Institute, a tax policy think tank that Ricketts founded.

Ricketts and family donated a combined $10,500 to three of McCollister’s earlier campaigns, including his first run for Legislature.

But after his time in the Legislature — where he frequently bucked his party — he ran for the MUD board again.

Gov. Ricketts and Marlene Ricketts donated a combined $12,000 to McCollister’s opponent, incumbent Mike McGowan, 65% off McGowan’s total that cycle and a dramatic change from the $0 he raised during his previous election in 2016. McCollister lost. Flanagain did not respond to a question about Ricketts’ motivations in this race.

“You’d go to the governor’s kickoff breakfast prior to a (Huskers) game, and he’d greet you warmly and everything else … And, you know, you could still see that affection that existed when I was at Platte,” McCollister said. “But yet, woe to somebody that crosses him during the legislative session.”

****

In the run-up before senators gathered in 2017, it seemed obvious January would bring “a different world,” said Kent Rogert, a former Democratic state senator who started lobbying in 2010.

It played out that first day, when it came time for senators to vote on who would lead the Legislature and its committees.

Sen. Jim Scheer won the open speakership over the more moderate Sen. Matt Williams, who had split with Ricketts on votes. Sen. Dan Watermeier, a Republican, ousted Sen. Bob Krist, a Democrat, as chair of the executive board.

They slotted Republicans — a couple brand-new to the Legislature — into other leadership positions, a handful previously filled by Democrats. Some refer to this day as the “red wedding,” said Walt Radcliffe, a lobbyist who has been working for or around the Legislature since 1969.

The Flatwater Free Press spoke to seven longtime observers of the Legislature for this story. All seven agreed that 2017 marked a notable change.

“I don’t think there’s any question about that,” Radcliffe said. “And I think we saw, after 2017, people more willing to go along with the governor’s budgets and his proposals.”

It’s a shift that many say still holds in today’s Legislature, though it’s Gov. Jim Pillen — who Ricketts supported and who later appointed Ricketts to the U.S. Senate — in the corner office.

“I think one of the outcomes of what Gov. Ricketts did is that it lessens the ability for us to have a decent political debate across the aisles,” said Kim Robak, a former Democratic lieutenant governor who’s worked around the Legislature for more than three decades.

****

At least two events primed Nebraska’s officially nonpartisan Legislature for increased partisanship before Ricketts became governor: the introduction of term limits and the lifting of campaign finance limitations.

In 2000, Nebraska voters passed a ballot measure limiting state senators to two consecutive four-year terms. Those limits first kicked into effect during the 2006 elections.

Term limits contributed to the Unicameral becoming more polarized faster than any other state legislature in the country in the decade leading up to Ricketts’ election, according to research from political scientists at the University of Denver and Georgetown University.

The Nebraska Supreme Court then unleashed political spending by striking down the state’s campaign finance law, following a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that deemed a similar law unconstitutional. The Legislature could’ve come back and placed limits on contributions, said Jack Gould, former issues chair for Common Cause Nebraska, which advocates for government transparency. They haven’t.

“They wanted a free-for-all,” he said. “So that’s what they’ve got.”

Heineman had already started getting involved in legislative races, observers said. When Ricketts entered the governor’s office in 2015, the stage was set.

Some observers say they see Ricketts’ legacy in the bitter divides that have become commonplace, and in the cutthroat campaigning for an office that pays a salary of $12,000 a year.

The last couple of legislative sessions have featured senators filibustering nationally driven conservative issues — abortion restrictions, limitations on care for transgender youth, and school choice — that ultimately made it over the finish line.

A 2022 analysis of statehouses across the country shows the Nebraska Legislature’s rapidly growing political divide continued to widen while Ricketts was in office.

“Nebraska continues to polarize,” said Boris Shor, one of the political scientists behind the research, in an email. “While the governor is a focal point for conservatives, he’s not the only reason. Lots of other states are polarizing as well.”

The same year Gov. Ricketts first spent big on legislative races also saw Trump elected to the White House and Republican control of Congress.

“I think a lot of factors came together which would allow what Pete Ricketts is doing — what the Ricketts family is doing — to have, probably, a bigger impact than it might otherwise,” Robak said.

Flanagain pointed to outside forces, saying that the national political climate changed in 2016, driving voters to pay closer attention to politicians’ actions.

Donors with more liberal political views influence the Legislature, too, some said. A recent report by the Revenue Committee raised concerns about whether organizations funded by the Sherwood and Weitz Family foundations were lobbying to influence policy with nontaxable funds that should be used for charity.

Another common counterexample: the Nebraska State Education Association.

“Money has always played a role in politics and in the Legislature,” said Radcliffe. “I have a favorite saying: If the Nebraska Legislature could be bought, the (Nebraska State Education Association) would own it.”

****

Ricketts has said he looks to support the most conservative candidate who can win. In some cases, that has been Republicans challenging Democrats. In others, it’s been hardline conservatives challenging more flexible Republicans.

But there’s at least one notable exception.

Sen. Steve Erdman, regarded as deeply conservative, attributes Ricketts’ support of his opponent in 2016 — who was also conservative — to his own critiques of the governor’s property tax relief efforts.

“When you have a lot of money, you want to make sure that you get what you can buy — and he can buy most anything because he has a lot of money,” said Erdman, who won his race. “So, what he did was inappropriate, and he will continue to do that as long as he has money.”

Not all of the senators Ricketts supported wound up voting lockstep with his agenda.

A bipartisan mass of senators still managed to override at least eight Ricketts vetoes in his second term.

Some of the senators he’s supported have become legislative heavyweights, and some haven’t.

Brewer, Bostelman and Halloran head up committees. But Bostelman and Halloran are probably best known to the public for controversial remarks made on the floor of the Legislature.

Bostelman repeated a baseless social media rumor that schools were putting litter boxes in bathrooms for kids who identify as cats. He later apologized. Halloran read a graphic rape scene during debate and inserted a fellow senator’s name. He apologized for inserting the name while he defended reading the passage. Both incidents attracted national media attention.

Brewer is known for his advocacy for Native tribes and Second-Amendment rights, ultimately passing a bill allowing concealed carry without a permit. Sen. Mike Hilgers, also in that 2017 class, became speaker and is now the state’s attorney general.

Sen. Lou Ann Linehan came into the Legislature with D.C. experience: former chief of staff for U.S. Sen. Chuck Hagel and State Department official under President George W. Bush. And she had long standing connections to the Ricketts family.

In the 1980s, she stuffed campaign envelopes with Joe Ricketts — Pete Ricketts’ father and co-founder of the company that became T.D. Ameritrade. She probably met Pete when he was a kid, she said, but most remembers him giving Hagel a tour of T.D. Ameritrade in the early 2000s.

She was impressed. She, and other Republicans, encouraged him to run for office.

Years later, he and his family gave $12,500 to her winning legislative campaign — including $5,000 from Ricketts’ wife Susanne Shore, who usually supports Democrats.

Linehan chairs the Legislature’s powerful Revenue Committee. She has championed major tax legislation and efforts to direct state funding to private school scholarships. She doesn’t agree with Ricketts on everything, she said, but a common interest binds them come election season.

Now, she names Pete Ricketts as one of the most influential political figures in recent Nebraska history.

As for his money? She’s grateful for it, she said. And, she and others said, opponents may be missing an opportunity.

“There are plenty of very, very wealthy Democrats in Nebraska — very wealthy,” Linehan said. “If they don’t want to play in politics, that’s a Democrats problem.”

Related Stories

-

Ricketts’ Riches: Record election spending shows senator’s family far from done in Nebraska

Sen. Pete Ricketts and his parents shattered their previous spending records during the recent election cycle. The family spent roughly $1 of every $11 spent by anyone on any Nebraska political race, PAC or ballot initiative. Much of it was on the white-hot abortion race. Read more »

-

Ricketts’ Riches: Wealthy governor widened gulf in Nebraska Legislature, observers say

While Pete Ricketts was governor, he and his parents spent serious money supporting state senators – and opposing fellow Republicans who had displeased the governor. Longtime observers say that money helped morph the Legislature, making it less independent and more partisan. Read more »

-

Ricketts’ Riches: Nebraska politician and family deliver deluge of campaign cash

THE SKINNY: Pete Ricketts and his family have spent at least $18.6 million on Nebraska political campaigns and causes in the dozen years he was running for governor,… Read more »

2 Comments

Our system of government is broken beyond repair. This is just more evidence of it. Oligarchs v Serfs.

Excllent reporting. Keep it up. Put this story in all CAPS and mail to every registered voter. I have been a Nebraskan for 73 years and now I watch a Unicamerial on bended knee.