If one of the iconic game shows Harry Friedman brought to new heights used his own bio as a clue, it might read something like this: Over two decades executive producing both “Jeopardy” and “Wheel of Fortune,” this native Nebraskan won more Emmy Awards than anyone in television game show history.

“Jeopardy” is now making news for all the wrong reasons, with a botched search to replace legend Alex Trebek and dismissal of new executive producer Mike Richards for offensive comments. But the prior wildly successful — and controversy free — decades of the show were led by Friedman, an unassuming Omaha boy who became a game show icon.

“It’s a developing story and I would prefer not to comment,” Friedman said of the game show’s current woes, speaking by phone from his home in Los Angeles. “But I can tell you I was not consulted during the selection process of the host candidates, and I didn’t really expect to be.”

Friedman’s enhancements to both “Jeopardy” and “Wheel” — eye-popping sets, entertaining remotes, and capitalizing on champions’ social media buzz — re-energized the brands created by Merv Griffin, and sent ratings and revenues soaring. He produced thousands of episodes, won 14 Emmys, accepted a prestigious Peabody Award given to “Jeopardy” in 2012, and got his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame just before retiring.

The two hosts he’s indelibly linked with explained his impact to Variety Magazine when Friedman finally hung it up in 2020.

“I will miss his tremendous talent, his unerring instincts and his genuine kindness,” said famed “Wheel” host Pat Sajak. “He is simply the best.”

“Harry is the most creative producer I’ve ever worked with,” said Trebek months before his death.

Making His Own Way

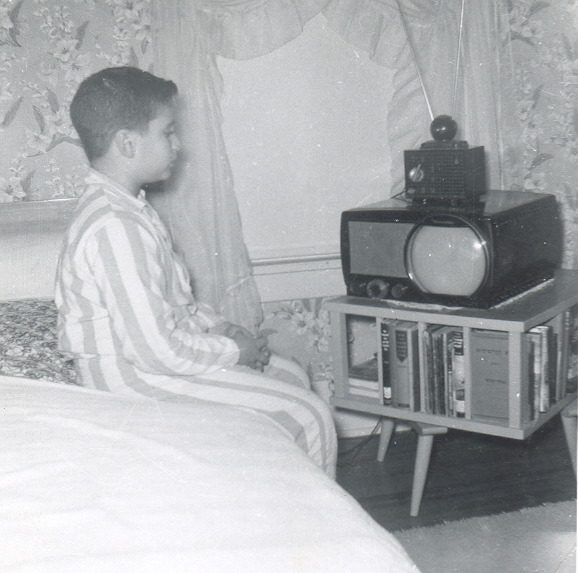

Friedman, 74, didn’t hail from a show biz family or study media production. But growing up in the Golden Age of television sparked an intrigue he nurtured into a career.

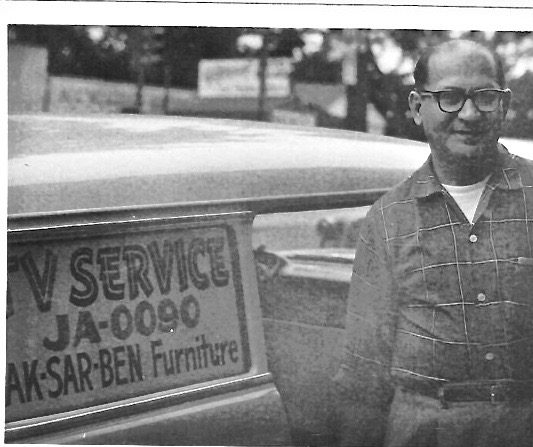

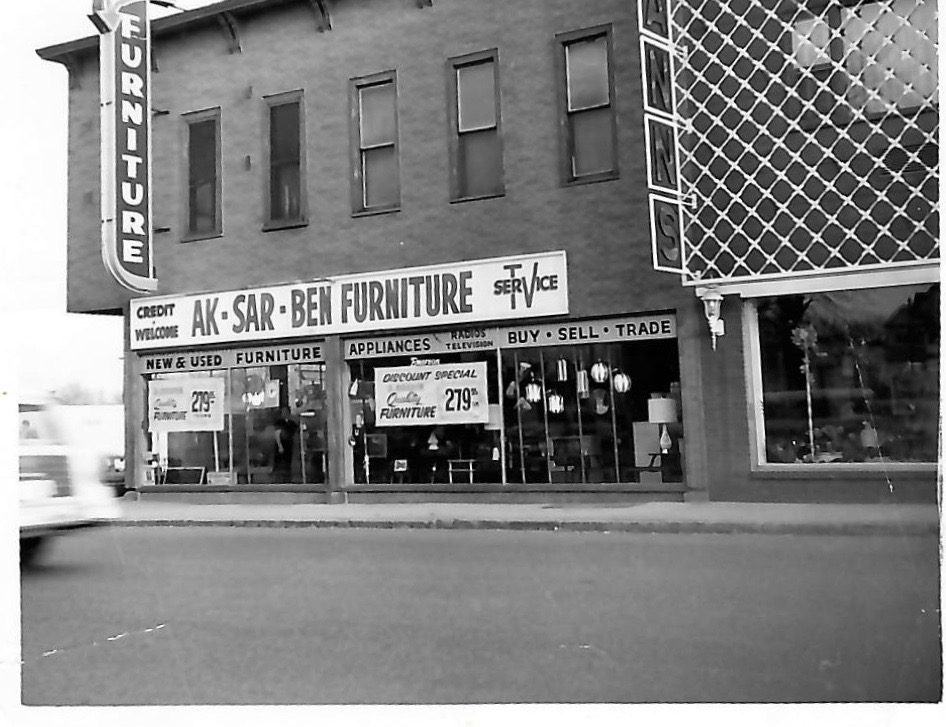

His Polish-Jewish emigre parents, David and Rose, met in Omaha. They belonged to Beth Israel Synagogue. His Mr. Fix-It father owned Aksarben Furniture and Television Repair near downtown. Today, Harry enjoys the symmetry: Dad a TV repairman; his son a TV content creator.

Friedman’s father saw TV as a household fixture — and an opportunity. The elder Friedman learned TV repair via how-to manuals ordered by mail.

Summers, Harry helped in the store. He watched as passersby stood transfixed in front of the TV playing in the front window.

“I suspect none of them had TV in their homes. I can picture those moments so clearly in my mind because I saw, then, the power of television.”

That appreciation for the medium grew when radio comedy stars, like Jack Benny and George Burns, moved to television.

“I loved those shows because they were sweet and funny and great escapism. It played well with me. I wanted to be a part of that.”

As a kid, he lived out a fantasy when Gregg Dunn, host of KMTV’s fright night show, “Gregore,” invited him behind the curtain.

A 10-year-old Friedman called Dunn at the station and invited him to his Halloween party. Dunn declined, but welcomed the fan to come watch the show, which broadcast live on Saturday nights. Friedman’s father drove him there.

Hungering for more, Friedman showed up at the station after school one day. No one stopped him, so he kept coming back. He peeked in on newscasts and met on-air talent, including future network newsman Floyd Kalber. Finally someone asked, “Who does this kid belong to?”

“I remember coming back a few more times … The fascination of it never left me.”

Bitten by the bug, he performed in plays and musicals at Central. He was Mayor Shinn in “Music Man” and the lead in “Fiorello.”

After graduating in 1964, he planned to move to the industry. Johnny Carson and Dick Cavett left here to make it in TV. Henry Fonda and Sandy Dennis made it on stage-screen. Why not him?

“I was naive enough not to think otherwise.”

His parents supported his improbable dream, or at least didn’t try talking him out of it.

“They knew it was a risky thing to do, and yet they also knew it was what I needed to do,” he says. He agreed to a six-month trial. “In my mind, failure was not an option. I had no plan B.”

He found work in L.A. before the self-imposed deadline, writing “patter” for cabaret singer Kay Dennis.

His break came in 1971, when, while freelancing on “Hollywood Squares,” he was offered a full-time job. He stayed a decade, writing jokes for star panelists like Paul Lynde, Rose Marie, George Gobel and Charlie Weaver.

Friedman also got a front-row seat to what it takes to be a producer – distribution, advertising, marketing, casting – a real-life education that would soon pay dividends.

Joining TV’s Franchise Game Shows

Friedman joined “Wheel” in 1995, added “Jeopardy” in 1997, then became executive producer of both in 2000. The special place these shows hold in families was never lost on him.

“It seems everyone I’ve encountered has a ‘Wheel’’ or ‘Jeopardy’ story of growing up watching with a parent or grandparent. It was a bonding experience. Or they remember a particular ‘Wheel’ puzzle or ‘Final Jeopardy’ question they got right but all three contestants missed.”

How cool, Friedman figured, “to get paid to go to work every day to do something that makes millions of people happy every night.”

He got to know King of Late Night, Johnny Carson, whose “Tonight Show” taped across the hall from “Squares.” Carson’s younger brother, Dick, directed “Wheel” for a time under Friedman.

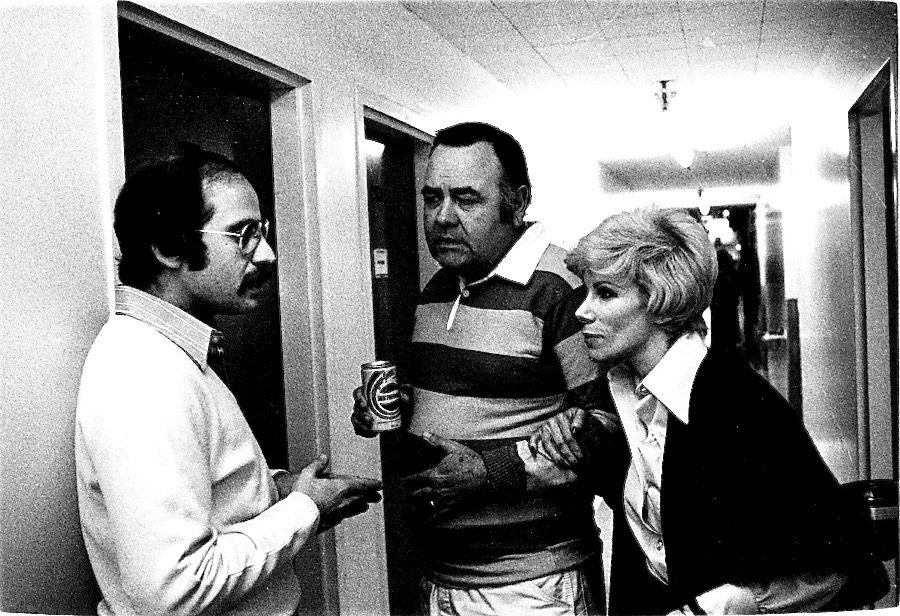

Friedman met many of the comic legends who first inspired him. He taped “Jeopardy” celebrity clues with heroes Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks.

A TV Home and Family

Nebraska “Jeopardy” clues sprang from an unusual confluence of natives on the show: Friedman, writers Steve Tamerius and Gary Johnson, and associate producer Stewart Hoke.

The intimacy of working with the same hosts, staff and crew promoted a family vibe. Sajak brought his wife when “Wheel” taped on location. Harry’s spouse Judy Friedman came along, too.

“We’re still friends to this day,” Friedman says.

Remote tapings of both “Jeopardy” and “Wheel” displayed the depth of fan passion. Audiences would roar when Pat Sajak and Vanna White were announced.

“The same thing when Alex was introduced. Overwhelming applause. But also smiles on people’s faces when they saw these ‘friends’ of theirs in person.”

The beloved Trebek waged a valiant fight against cancer, often hiding the pain and his treatment’s side effects from public view.

On the last tape day Friedman spent on the “Jeopardy” set, March 11, 2020, Trebek showed up “feeling groggy and looking awful.”

“By 11, when he was being introduced for the first show … Alex had somehow been transformed and summoned the strength to be the masterful host everyone knew and loved,” Friedman says.

The staff and crew wrapped for the day, thinking they would be back in a few weeks after this new virus called COVID-19 had passed. It was the last time many saw Trebek in person.

“The last time I spoke with Alex was by phone on November fifth, just three days before he passed. We both knew it would be the last time we would speak.”

Trebek’s popularity, Friedman believes, was a product of the fact “he didn’t just read the clues, he presented them.” That ability to paint word pictures, a skill honed as a Canadian broadcaster, resulted from precise timing, phrasing and emphasis.

Trebek also worked doggedly. Friedman recalled Trebek’s tape day ritual of arriving early to study clues in the five games being taped. “More often than not he would say, ‘Hey, you know what I just learned about?’ and he would cite something from one of the clues being presented that day.

“He was smart as hell and curious,” said Friedman. No matter who replaces him, Friedman said Trebek will always be the face of “Jeopardy.”

As for his own legacy, Friedman regards his run with those career-making shows as “certainly something very special.” He regrets his parents didn’t live to see him lead them.

In 2018, Friedman suffered a serious health scare, though he’s since recovered. “Something like that makes you…reflect on where you are and what you want to do. After I was fully recovered I made the decision that when I reached 25 years (since joining ‘Wheel’) it would be a nice number to retire on.”

Retirement has been busier than anticipated. He’s consulting for production companies and even entertaining the idea of another full-time gig. Even if that doesn’t happen, he remains good fodder for a trivia puzzler.

Friedman doesn’t boast about the Guinness Book of World Records mark he holds for most game show episodes ever produced – 12,540. The low-key producer left “Jeopardy” and “Wheel” quietly, at the height of the pandemic, with two Zoom parties – one for each of his work families.

It’s not the way he wanted to say goodbye, but it was fitting for this ultimate man behind-the-scenes.

1 Comment

Nice article! And no I didn’t know this!