The land John Childears farms near North Platte is sandy, not particularly fertile, less than ideal.

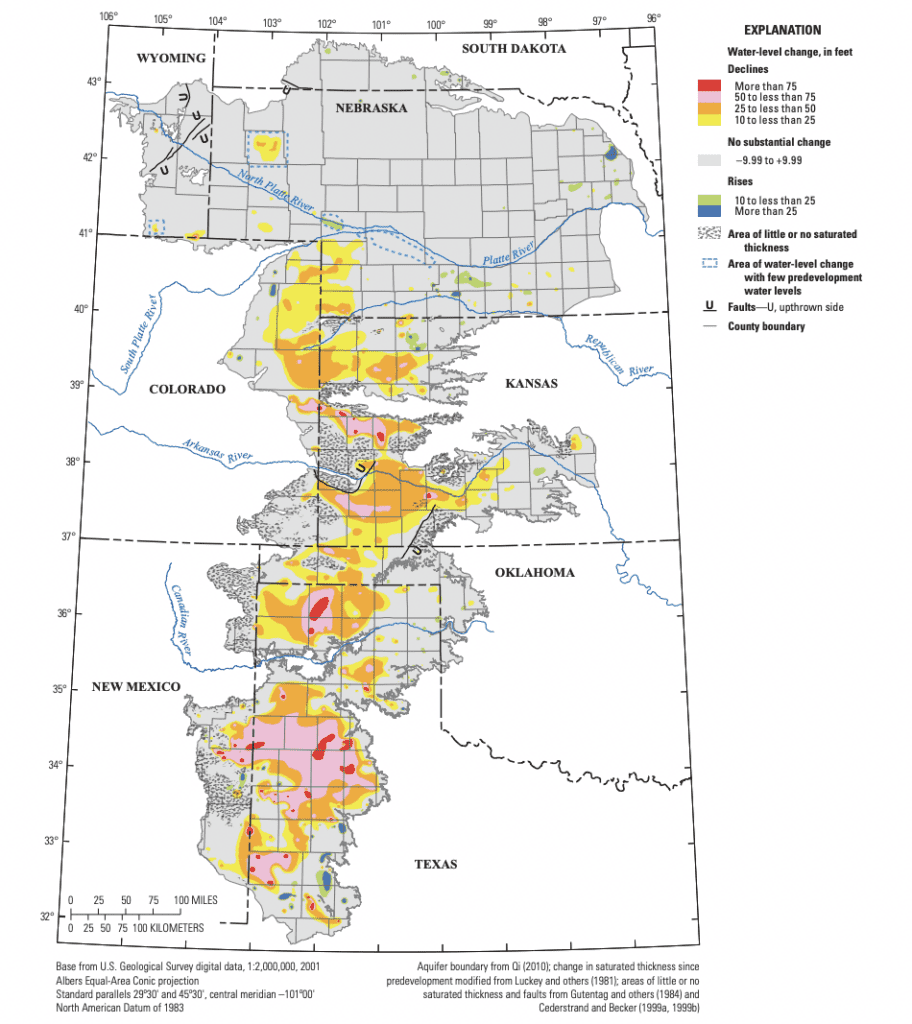

But the value of his land largely lies beneath his feet: the Ogallala Aquifer, one of the largest in the world.

Childears recently harvested corn at 225 bushels per acre, utilizing center pivots he put in and, crucially, his irrigation wells, including one dug before he bought the land three decades ago.

The farmer says he couldn’t even grow corn without those pivots – all his land would be far less valuable rangeland.

“Water is what gives life, what allows the deer to be there, what allows man to be there, and what allows men to grow crops,” he said.

And, in Nebraska, water is a linchpin of the ag economy.

Childears’ land is even more valuable today because local water regulators no longer allow additional irrigation wells to be drilled. The farmer, also an appraiser who has evaluated the value of central and western Nebraska farmland for more than 40 years, says he can’t put a price tag on water.

“I’m a really smart guy, but … I can’t tell you what that value is. Except it’s a heck of a lot,” he said.

As out-of-state investors spend big dollars buying up large amounts of Nebraska farmland, some worry about what that could do to the state’s water resources. Could these landowners claim, strain and deplete the finite resource and leave Nebraskans out to dry?

Regulators, legal experts and farm brokers say that concern is overblown. Landowners don’t own the water in Nebraska, they said. Regulators closely scrutinize water use. They don’t allow large amounts of water to be transported across property lines or state lines without a permit.

Most acknowledge that out-of-state buyers are attracted to Nebraska land, and that attraction is in large part based on the natural resource beneath it.

Recently, farmland Realtor Steve Linden said he’s seen an uptick in interested buyers from states like Oklahoma and Texas – states where groundwater is becoming increasingly scarce.

“They just continually do not have any crops,” Linden said. “They don’t have hay for their cattle or pasture for cattle to graze, and so they want to come up here.”

Oklahoma and Texas treat groundwater rights as property rights, rarely restricting water use – a free-for-all that’s hastened the aquifer’s decline in some places, said Dean Edson, executive director of the Nebraska Association of Resources Districts.

“It’s what I call ‘The guy with the deepest and biggest well wins,’” said Edson. “That doesn’t happen in Nebraska because it’s not a mineral right – you don’t own the water that’s underneath your land.”

In Nebraska, he explained, landowners instead have the right to use water with restrictions, because state leaders designed it that way decades ago.

Surface water falls under the jurisdiction of the Nebraska Department of Natural Resources, while local natural resources districts – a system unique to Nebraska – manage groundwater.

NRD leaders monitor water levels, account for all water usage in their districts and often lay down restrictions.

Some districts have put into place a well moratorium, where no additional irrigation wells can be drilled. Others don’t allow a farmer to add more irrigated acres, or limit the amount of water producers can put on their crops. The restrictions have often led out-of-state investors to buy irrigated land that already comes with a well, Childears said, avoiding the drought risk associated with non-irrigated, or dryland, crops.

The Nebraska Department of Natural Resources has granted “a limited number of out-of-state transfers,” said Tom Riley, the agency’s director. These transfers were meant to help ag producers use water more efficiently, he said, for instance, allowing a center pivot straddling state lines to irrigate land in a neighboring state.

The South Platte NRD is home to three Panhandle counties, Kimball, Deuel and Cheyenne, that attract some of the highest percentages of out-of-state buyers, according to a Flatwater Free Press analysis of farmland sales data gathered by a UNL College of Journalism and Mass Communications data journalism class.

South Platte NRD manager Galen Wittrock says those out-of-state buyers do come for the water – but only to use it to farm the land.

“The NRD system, it’s great because within the groundwater controls that we have, we can be proactive and work towards restricting what can and cannot be done,” Wittrock said.

Many investors do come to Nebraska knowing the abundance of ground and surface water gives them more yield and offers drought protection, brokers told Flatwater.

Irrigated farmland is worth more than $12,000 an acre on average in eastern Nebraska. In comparison, dryland with no irrigation potential is worth about two-thirds of that price, according to a UNL annual survey.

In the Nebraska Panhandle, where it often rains less than 20 inches per year, irrigation can triple the size of a corn crop – or simply make it possible to grow corn at all, Childears said.

In parts of Nebraska that ban adding new irrigation wells, dryland fields that have the aquifer lying beneath them but can’t be irrigated lose roughly 9% of their value, according to initial findings by Aakanksha Melkani, a researcher at the University of Nebraska’s Daugherty Water for Food Global Institute and the National Drought Mitigation Center.

But a water allocation system, including a cap on the amount of water the landowner can use to irrigate, doesn’t appear to impact farmland value, her initial research shows.

In the North Platte river basin in the Panhandle, farmland with access to both groundwater and surface water costs $1,000 to $1,500 more per acre when compared to parcels with only one type of irrigation, said NRD manager Scott Schaneman.

The dual water source has enabled producers to grow a variety of crops such as corn, dry beans, sugar beets and alfalfa. It also holds an appeal to potential buyers, Schaneman said.

“I think a lot of investors are really starting to look at the western end of the state saying, ‘Hey, the land prices are still pretty reasonable … and they have the capability of growing 200-bushel corn (per acre) with the water. Maybe this is a place I need to look at,’” he said.

As western states increasingly grapple with water resource depletion and shortage and eye Nebraska farmland, Melkani said it may drive up Nebraska’s farmland value.

Colorado farmers have been paid to fallow their irrigated acres to cut down water usage.

Some of these Colorado farmers have moved to Nebraska or bought Nebraska farmland that gives them access to surface water, said Dan Lindstrom, a Kearney-based attorney specializing in water laws.

In Arizona, the governor terminated a lease with a Saudi-owned company that used groundwater unchecked to grow alfalfa, a violation of their lease terms.

But in Nebraska, NRD managers interviewed by Flatwater said they haven’t noticed any excessive water use on farms tied to out-of-state owners. Many of these owners employ local operators and farm largely in the same way as others.

In some cases, landowners can sell water rights separately. In some NRDs, a seller with certified irrigated acres they’re not using can strike a deal with a buyer, where the seller gives up irrigation on certain acres and transfers the water rights to the buyer.

“It’s not like one guy is selling 20 acres of his water, and then … pump it 5 miles to the other guy’s property. That is not happening,” said Central Platte NRD manager Lyndon Vogt. “They’re really selling their right to irrigate that ground.”

These transfers don’t happen regularly and often involve small plots of land, NRD leaders and brokers said.

And they need approval from NRD leaders. In Vogt’s district, new irrigated acres can’t be transferred upstream for more than a mile, he said.

Sometimes the irrigation rights can be transferred to non-ag use too, Vogt added, noting an ethanol plant in Wood River purchased irrigated acres and “dried up a number of acres” to offset the plant’s own water use.

Economic development outfits in several cities, including Gothenburg and Grand Island, also acquired irrigated acres because of growing water demand from industrial use, he said.

Cities in Arizona, Colorado and California have paid farmers for rights to use water.

So far, Nebraska towns have been able to find willing producers to trade their water rights. But municipalities’ water needs will likely expand as industrial developments and urban residents demand more water, said Dave Aiken, a University of Nebraska-Lincoln professor and extension water law specialist.

“With all the challenges that we’re going to be dealing with in terms of global warming, we can have a lot worse problems than not being able to irrigate as many acres here and there in Nebraska,” Aiken said.

Flatwater Free Press reporter Destiny Herbers contributed to the data analysis used in this story. The series, “Who’s Buying Nebraska?” was made possible by a grant from the Center for Rural Strategies and Grist.

Who’s Buying Nebraska?

A Flatwater Free Press series is focused on the answer to that question, and diving deeper into the corporate farms, multinational corporations, famed billionaires and even a powerful church who are buying huge swaths of Nebraska farmland.

2 Comments

Doing a great job with stories about our land!

Thank you, again, for doing the research, asking questions, and connecting the pieces so that we can see what underlies the surface story.

Please keep digging – beneath what the NRD leaders are saying, though. While it may seem like conjecture, asking questions about how NRD makes their rules, and what it might take to change them in the future as our realities change might surface some interesting concerns. When connected with what other federal agencies, including the USDA have done to “water down” rules so that large corporations can continue their practices, might provide a pattern for what to expect with water, water rights, wells, and the Ogallala Aquifer.

It may seem a bit of a stretch to many, but not for others. For instance, while the Gates family monies are being used to purchase land and future access to water in Nebraska, and Gates Foundation has a sustainability focus, they claim the two are not connected/related. Dig deeper and see if what they say holds up. What does sustainability look like in the grant making of the Gates Foundation? Sustainable for whom? Who are the “winners and losers” in their social engineering? Do those funding preferences suggest what they may be up to with Nebraska land and water?

Or is Gates so greedy that he needs to leverage $700M in land value for a loan for personal use? When he “earns” $2.8B a year?

Please don’t leave us at the water’s edge, close enough to see, but too far to drink from the source.