Tim emakiyapi. My name is Tim.

Omaha ed wati. I live in Omaha

ISanti Dakotah hemahantan. Do. I come from the iSanti Dakotah (Santee Sioux).

It sounds so simple, but learning to introduce myself in the traditional Dakota language formed a powerful connection to my ancestors. It also made me part of a collective effort to keep the Santee native tongue alive.

Despite there being 27,000 Santees scattered across the United States and Canada, including 3,000 in Nebraska, only 15 are fluent speakers. Without active speakers, a tribe risks its language becoming a dead one.

It’s a perilous reality for the Santee and other tribes.

“Without our language, we die as a people,” said Redwing Thomas, the tribe’s cultural officer and leader of the language program. “The drum is the heartbeat of the tribe, but language is the soul.”

Four Nebraska tribes are working to keep that soul alive. From using traditional words during powwows to signs around reservations, Indigenous communities are reclaiming their stories.

The Omaha and Winnebago prioritized language years ago. The Northern Ponca, by comparison, are in the beginning stages of language education efforts.

Santee tribal leaders obtained a federal grant two years ago to help tribes with language, said Kameron Runnels, vice chair. The Santee tribal council also took a bold move by financing language courses for all tribal citizens and non-enrolled children of Santees.

“Fifty years ago, you could walk down the road and hear our grandparents speaking Dakota,” Runnels said.

My grandparents were among the first language speakers. My grandfather left a federal government-sponsored residential school after third grade because he refused to give up the language.

My grandmother attended a Episcopalian-led school where speaking Dakota was encouraged. The federal government eventually cut off funding for that school, determined to rid the Santees of their language.

Grandpa Trudell refused to teach my older siblings the language – beyond a phrase or two – because he determined there wouldn’t be a need for it in the future. Unfortunately, this was one time he’d be wrong.

Today in Santee, elder Donald LaPointe is the lone fluent – or first language – speaker, and he’s in his mid-80s. Others are considered proficient.

“If we don’t do something now, we will cease to exist as a people,” Runnels said.

As an elder – a strange admission when you’re the ninth of 10 children – I saw learning Dakota as a way to grow closer to my ancestors. My daughters Steph and Mallory and I were among the 20 students in an online class hosted through the Nebraska Indian Community College.

Another 20 people participated in an in-person class in Santee, and about 25 took classes in Sioux City, Iowa, an urban hub for Santee citizens.

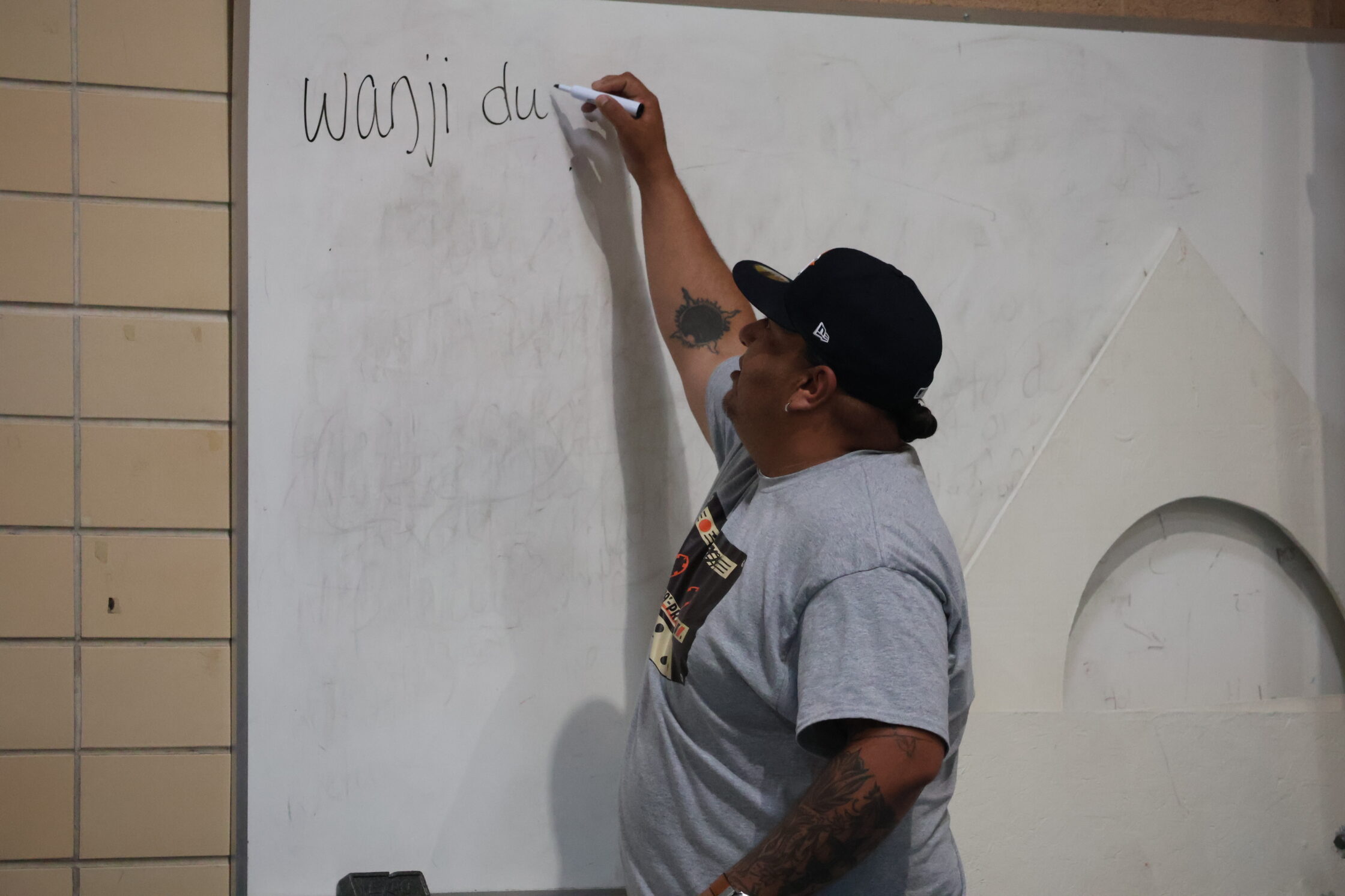

Rather than focus on basic lessons such as learning colors or how to count to 10, Thomas teaches students how to create sentences, so they can start having conversations.

“You have to use it daily to know the language,” he said. “Once you learn a few words, it helps in picking up more and then understanding what people are saying.”

For Sheldon Bird and Aracely Figueroa, the Santee program is helping them reconnect to tribal roots and laying the foundation for the future.

“It’s a great empowerment movement for my cultural reasons,” said Figueroa, 21. “It’s going to help me in the future, to teach younger adults the language. And it helps us here in Sioux City with the people who are from the reservation in learning the language, as well.”

The 26-year-old Bird, who’s majoring in the Dakota language and took the classes online, anticipates becoming one of the tribe’s youngest fluent speakers.

“It’s a lifelong mission,” he said. “I need to listen to the elders and learn from them.”

In some ways, efforts to resuscitate Native languages are a way to counteract past injustices.

Native Americans have experienced years of reservation life, forced assimilation, tribal termination and relocation to residential schools designed to eradicate Native culture.

During a nearly 20-year period starting in 1953, the federal government terminated recognition of dozens of Native tribes across the U.S., resulting in the relinquishment of more than 3 million acres of tribal lands. The Northern Ponca, based in Niobrara, were among those removed from federal rolls, essentially leaving them without community. Their language was among the cultural casualties.

“My great-grandparents used to host powwows at Ta-Ha-Zouka Park in Norfolk, and do what they could to really keep the culture together and the language, but it definitely hurt when we were all dispersed and kind of went into the urban areas,” said Ricky Wright Jr., the Ponca’s cultural affairs officer.

Without any fluent speakers, the Northern Ponca’s traditional language died.

Since the tribe’s restoration in 1990 as a federally-recognized Indigenous nation, one goal has been to resurrect their language.

Today, five designated language teachers are undergoing an intensive education program with a fluent speaker from the Oklahoma-based reservation, Wright said. They plan to roll out a program in 2025 that will station a language teacher at each of the tribe’s five offices in Nebraska.

Instructors will work with the tribe’s 5,500 citizens, as well as non-Poncas interested in learning the language, Wright said. Classes will be hosted weeknights and on weekends.

“The language has been vacant for so long that we don’t want to keep it from others. We want to share it,” Wright said.

The language program will be a source of tribal pride, he said. Other tribes, which managed to hold onto their language and culture, would occasionally mock Ponca people, Wright said while reflecting back on his childhood.

“I love being the front of the spear, as the culture director, in leading us back, so that someday, my children can be proud to say, ‘Hey, I’m Northern Ponca,’” he said. “It’s been a great turnaround and the vision is becoming clear.”

It took 20 years of on-and-off attempts at language preservation for the vision to become clear for the Winnebago.

The tribe launched Ho Chunk Renaissance in 2015 to keep its language alive.

“The language is the spirit and the culture is the body,” said Lewis St. Cyr, who’s been executive director of the program for the past nine years. “The spirit drives the culture.”

Ho Chunk Renaissance offers its courses through outreach programs with area schools and community programs, such as its annual summer camp, pumpkin carving contests and language classes, St. Cyr said.

After years of resistance from administrators, Winnebago schools now display Ho Chunk art and words, he said. Native speakers lead language immersion programs at the elementary school, which also meet Nebraska education standards.

Children are learning language and culture from head start through high school, but because of a lack of fluent speakers, Ho Chunk Renaissance focuses on first through fourth grades and high school, he said.

The Omahas (Umo Ho) realized the importance of saving and growing their language decades ago. For about 20 years, children at the Omaha Nation schools have learned their language.

Still, progress has been slow. The tribe has about 7,000 members but less than 10 fluent speakers, said Dwight Howe, executive director of the Omaha Nation Family Resource Center. The language’s absence at home hinders the school’s program.

“How can we expect them to speak the language if there’s no one at home to speak it with?” Howe said.

Recognizing the need to help grow the language, Howe’s organization seeks different ways to spread the word, including stop signs in both English and Omaha, located around the Thurston County reservation. And Howe tries to host classes for adults when they’re most effective, such as during an elders luncheon, as well as evening classes to maximize results.

“It’s difficult to do an immersion program, so we have to find different ways to teach the language.”

While Nebraska’s Indigenous tribes have started the linguistic healing process, leaders realize they’re playing catch up after decades of silence.

“If we don’t do this now,” said Santee’s Runnels, “our people as a tribe will be gone in three generations.”

2 Comments

Question: How many Western Hemisphere languages were rendered extinct by intertribal warfare before 1492? Dozens? Scores? Hundreds? A thousand?

Wonderful! Bringing back your roots, customs and languages. So important!! Our heritages are something to honor and deter those who would try to wipe us out. As one who is born and raised Jewish, not just a religion but an ethnicity; my people are very familiar with that!

I hope all your projects to recreate your languages and use of them on a regular basis works out!!